Let's Understand How a CPU Works

Designing a CPU from the ground up, with no knowledge needed

Chapter 10 - Sequential Logic

Topics Covered: Determinism vs Non-Determinism, Latches

⚠Warning: This and the following chapter will be the most confusing in the book for most readers. Please don’t get discouraged here, take the time you need to make sense of everything and you will find that the rest of the book is far easier to process and more rewarding.

You’ve seen a decent number of circuits created by logic gates so far, and have even built up the first component of the CPU, the ALU. But, we can’t progress any further without having a way to store data. What is the point of having an ALU that can add and subtract numbers if we have no means of storing the result? The answer is that there isn’t really a point.

So the focus of the next few chapters will be solving this issue. In chapter 6, I told you that we can build an entire computer out of logic gates which means that we also have to be able to store binary values with logic gates. You might be thinking that this is impossible, but it turns out we can manipulate logic gates to create circuits that store bits!

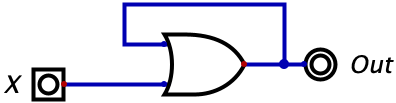

Until this point, every logic circuit we have introduced has been deterministic. This means that the output of the circuit depends strictly on the inputs, and whenever you set the inputs to a given value, the output will always be the same. This may sound obvious, but take a look at the circuit below.

This should look very confusing - we have the output of a logic gate feeding back into the input of a logic gate. Is this even valid? The answer is yes, and it is this exact mechanism that enables us to store information in logic gates. But let’s look at this gate a bit closer to see what happening. The first claim which I will make is that, at the initial configuration, the output of all logic gates is zero. Just assume this to be true for now, and over the next few chapters it will become clear why this is a convenient assumption to make.

So, we start with this circuit where \(X\) is initially zero and, by assumption, the output of the logic gate is zero. This means that, assuming we leave everything alone, the two inputs to the logic gate are both zero, so the gate will output a zero. The interesting case arises when we then switch the value of \(X\) to 1.

When that happens, one of the inputs to the OR gate is now a 1 (namely the bottom input in the diagram), so the overall output of the gate becomes a 1. Since the output of the gate is being fed in as the top input, this means that there is now a 1 on that wire which is being fed into the gate. So, both of the inputs to the OR gate are one.

Now, suppose we turn off the input \(X\) so it becomes a zero. What should happen? In this case, the output stays as 1! This is because the output of the gate right before we turned off \(X\) is a 1. This value is ‘trapped’ on that upper wire. When we turn off \(X\), the output of the gate stays at 1 because the top input is 1. Similarly, the top input stays as 1 since the output of the gate is still a 1. So now, no matter how much we toggle \(X\) on and off, the output of that logic gate will always stay at 1.

If you’re anything like I was, you should find this incredibly confusing. Sit down for a minute and really think about what’s happening here.

If we had to describe the behaviour of the circuit in English, we could reason as follows: “The value of output will be a 1 if X was, at any point in history, a 1. If X has always been zero, then the gate will output a zero.”

Now in all honesty, reading that explanation might have made you realize that this is a pretty useless circuit. It doesn’t serve a valuable purpose besides me confusing you. But what this does introduce is the idea of non-determinism. We originally said that all of our previously encountered circuits are deterministic because they always give the same output for a fixed input. Here, however, we have found this to not be true. We saw two different scenarios where the input was a zero but in one case the circuit outputted a 1 and in the other case a 0. This is the essence of non-determinism: the output of circuits now depends both on current inputs and previous inputs. For these non-deterministic circuits, which I will also refer to as sequential circuits, the concept of using a truth table no longer makes sense since the information in each row (i.e. the current inputs) is not enough to explain the output. In some cases, we can modify our truth tables to include previous inputs and then truth tables may be used, but in many cases, this is not practical.

Latches

Now that we have introduced sequential logic, it’s time to see how we can create sequential circuits that store information. The first circuit we will examine is called a latch.

A latch takes two inputs: D which represents data and S which represents the set line. The latch will output a singular value, Q.

The latch behaves as follows. The initial output of the latch will be 0. As long as S is 0, the output of the latch will not change. However, to change the value of Q, you must change S to 1 and Q will read the value of D (you can set D to whatever input you’d like). In other words, when S is 1, the latch will output the value of D. When S goes from 1 to 0, the circuit will ‘latch’ onto the last value of D and save that as the output value.

This circuit allows us to save the value of D at the exact moment that S goes from 1 to 0. While S is 0, the output Q, will not change (and it will be whatever the value of D was at the moment S became 0). While S is 1, the output will equal whatever the value of D is. So, if we have some value ‘saved’ in the latch and we want to save a new value, we put the value on D, and then set S to 1 and back to 0. At the moment S goes from 1 to 0, the value on the line D will be latched in (hence the name) and will become the output of the circuit. As long as S is 0, the latch will output this same value, and it is safe to change the value of D without affecting the output of the circuit.

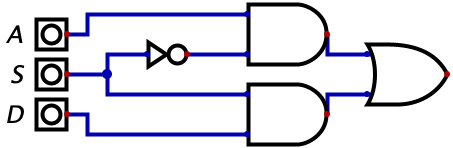

So, how exactly do we build this circuit? Well in chapter 6, we saw how we could build a switch. Here was the final circuit we ended up with.

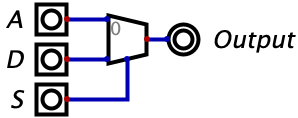

It turns out the switch, also known as a multiplexor (which we learned more about in Chapter 8), is so common that we have our own symbol used to represent the switch. That diagram is given below.

The two circuits are equivalent. When \(S=0\) the output equals \(A\) and when \(S=1\), the output equals \(D\).

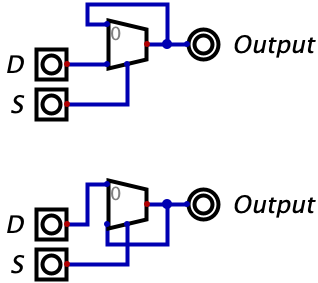

It turns out that if we make the following, seemingly minor, modification to the switch, then we end up with the described latch.

Seeing this diagram should help you reason through why this works as a latch. When \(S=1\), the switch is just selecting to output whatever is on the input \(D\). At the moment \(S\) goes from 1 to 0, the switch changes to select from its other input, which was its current output right before \(S\) became zero. So you can see that when \(S\) goes from 1 to 0, the value of \(D\) is latched in! This should also be a bit confusing, so take some time to reason through what is happening.

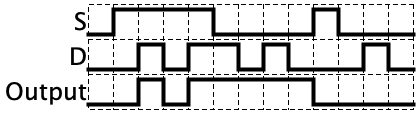

I previously mentioned that we have no truth tables for sequential circuits, but we can show a timing diagram which shows all of the historical inputs/outputs of a circuit. A timing diagram is given below for this circuit with the comment that the horizontal dimension is time.

This has all been explained, but the key observations you should understand are as follows:

- When \(S=1\), the output follows \(D\)

- When \(S\) goes from 1 to 0, the value of \(D\) is trapped and becomes the ‘saved’ value on the output

- When \(S=0\), the output never changes, even if the value of \(D\) changes

If all of the behavior in the timing diagram is clear to you, then you have understood 95% of what you need to know about latches. The next subsection will explain the remaining 5%.

Negative vs. Positive Latches

Congratulations on understanding the majority of latches. One small remark will conclude this chapter.

What we have looked at so far is more formally known as a Positive Latch. ‘Positive’ comes from the fact that the output only changes when \(S=1\).

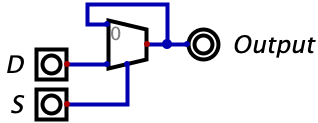

It turns out that a Negative Latch has the same behaviour but in the opposite direction. The negative latch only changes values when \(S=0\). We can construct a negative latch by swapping the two inputs of the switch that we used to construct the positive latch in the prior subsection. The image below shows a positive latch (on the top) and a negative latch (on the bottom).

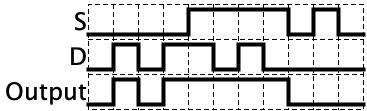

The key observations you should understand about the negative latch are the exact opposite of those from the positive latch:

- When \(S=0\), the output follows \(D\)

- When \(S\) goes from 0 to 1, the value of \(D\) is trapped and becomes the ‘saved’ value on the output

- When \(S=1\), the output never changes, even if the value of \(D\) changes

For sake of illustration, I have included a timing diagram of a negative latch below.

That’s all you need to know about latches! You will see why I made the distinction between positive and negative latches in the next chapter.