Let's Understand How a CPU Works

Designing a CPU from the ground up, with no knowledge needed

Chapter 09 - Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU)

Topics Covered: ALU

Now that we understand some of the funamentals of how numbers and logic are represented in the computer world, I think it is time we broaden our knowledge by introducing the Artithemtic Logic Unit, ALU.

What is an ALU?

ALU can simply be defined as a circuit which allows us to perform arithmetic and logical operations using binary numbers. The ALU is where all of the processing in a computer occurs (so you can think of it as the main unit in the computer). You might have heard of the Central Processing Unit, or CPU, being called the “brains of the computer”. Technically speaking, in modern computing, the ALU is actually a component that is part of the CPU. However, for our purposes, we are going to keep it simple and learn about the ALU first. ALUs are actually one of the oldest concepts in computer science and were originally suggested by John von Neumann in 1945, so a lot of older computers actually have basic implementations of ALUs and the only thing they could do was simple arithmetic and logical operations!

You might be asking yourself how is an ALU different than a Ripple Carry Adder, an Adder-Subtractor, etc. An ALU allows us to perform more operations than just adding and subtracting and allows us to choose which operation we want to specifically want to perform.

So we have defined what an ALU is, you might now be wondering what it consists of? I think it would be helpful to break it down into three simple parts: the input, the opcode, and the output. Let’s try to define what each of these parts are and how they function:

- Input: The input is what you think it probably is. The ALU will take in two binary operands and we can define both of these to be n bits (they should equal the same length). Simple right?

- Opcode: This is where the ALU gets interesting and relates to what makes an ALU different than what we have already learned. The opcode is an m-bit input into the ALU which allows us to execute different operations depending on the combination. So a 1-bit opcode will allows us to perform 2 various operations, 2-bit opcode will allow us to perform 4 various operations, a 3-bit opcode will allow us to perform 8 bit operations, a 4-bit opcode will allow us to perform 16 operations, and so on. As you can see, the general rule we follow for determining the number of operations we perform based on an n-bit opcode is \(2^n\). So you might be wondering what these operations consist of. The opcode can essentially define various arithemtic operations such as addition, subtraction, incrementing, and decrementing; bitwise logical operations such as AND, OR, XOR, One’s Complement; and, bit shift operations such logical shift or arithmetic shift. For our purposes, we will start out building an ALU with 4 different operations (add, subtract, bitwise AND, and shift left). Moreover, the ALU also calculates the result for all of these different operations at one time after the inputs get fed in, and then the opcode is used to select the output that we desire (this will make more sense as we start building our ALU).

- Output: Lastly, we have the output. This just represents the result of our operation. We can also have flags from our calculation such as a carry flag which specifies if there was carry-over (which is only used in unsigned arithmetic), overflow flag which specifies if there was an overflow (which is only used in signed arithmetic), zero flag which specifies if the actual result was 0, and negative flag which specifies if the result was negative.

Bitwise Operations

In our explantion of an opcode, we came across a term: bitwise. Bitwise operations basically perform any logical operation (such as AND, OR, NOT) on each corresponding bit when given two n-bit binary values. So let’s take a simple example. If we were to perform an AND operation on 1111 (Nibble A) and 1010 (Nibble B), here is how that would look like:

| Bit #4 | Bit #3 | Bit #2 | Bit #1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nibble A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nibble B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Result | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Notice how we perform an AND on each place value or each corresponding bit. This same idea applies to the other bitwise operations also.

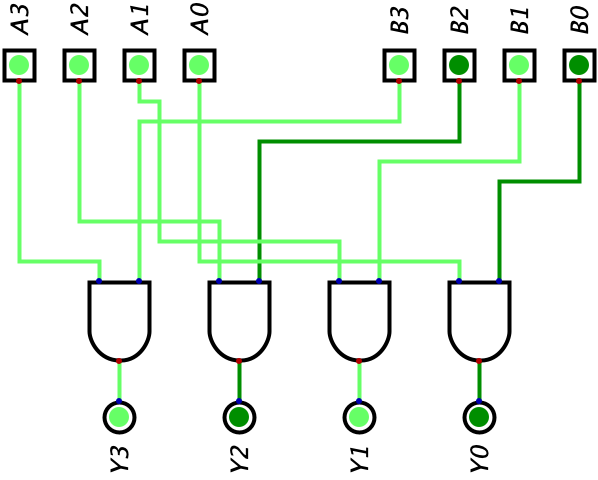

Below is a circuit that represents how to perform the AND bitwise operation on two 4-bit binary values (we use the same inputs and values as the above example):

Bit Shift Operations

We also ran into another term that didn’t seem familar: bit shift. Bit shift operations are essentially a way to multiply or divide the number by 2. Say you were presented a binary value of \(0110_{2}\) (which is \(6_{10}\)). If we shifted all the bits to the left by 1, it would become \(1100_{2}\) (or \(12_{10}\)). Now, let’s try the opposite and shift the original value of \(0110_{2}\) to the right. Now, this would become \(0011_{2}\) (or \(3_{10}\)). Cool right! So, it turns out shifting the digits to the left means that we are multiplying the number by 2 and shifting the digits to the right means we are dividing by 2. However, depending on if we are dealing with unsigned or signed numbers, the bit shift operations behave a bit differently.

With unsigned binary values, we use the logical bit shift. Below are two explanations on how to perform a left logical shift and a right logical shift respectively:

- When we perform a left logical shift, each bit is shifted to the left by one position, the LSB is replaced by a 0, and the original MSB is removed. So, if we had the byte \(01100101_{2}\), and we performed a left logical shift, our result would be \(11001010_{2}\). Our original byte had the numerical value of \(101_{10}\). After our left logical shift, the value of our byte is multiplied by 2 meaning it’s value is \(202_{10}\).

- Now, let’s look at how to perform a right logical shift. When we perform a right logical shift, each bit is shifted to the right by one position, the MSB is replaced by a 0, and the original LSB is removed. Let’s use the same byte we used in the example above: \(01100101_{2}\). After we perform the right logical shift, our byte becomes \(00110010_{2}\) and has a value of \(50_{10}\).

Now that we understand how to use the logical bit shift, let’s take a look at the arithmetic bit shift. We use the arithmetic bit shift when working with signed binary values (in other words, two’s complement numbers). Below are two explanations on how to perform a left arithmetic shift and a right arithmetic shift:

- When we perform a left arithmetic shift, we are doing the same thing as we did with the left logical shift. Essentially, each bit is shifted to the left by one position, the LSB is replaced by a 0, and the original MSB is removed. Let’s go through another example. Suppose we have the byte \(00010101_{2}\) (can also be represented as \(21_{10}\)). When we perform a left arithmetic shift, our byte becomes \(00101010_{2}\) (which is \(42_{10}\)). Simple right?

- The right arithmetic shift is a little harder. Depending on the value of the MSB, we insert the same value bit. So, if the MSB is equal to 1, then we insert a 1 and if the MSB is equal to 0, then we insert a 0. After inserting in the proper bit into the MSB, we shift all the original bits to the right by 1, and remove the original LSB. Let’s look at a quick example. If we had the byte \(11001100_{2}\) (which is equivalent to \(-52_{10}\)) and performed a right arithmetic shift, the result would be the byte \(11100110_{2}\) (which is equivalent to \(-26_{10}\)).

Aside: When performing division on an odd number, you might notice that the result isn’t an integer. However, with the right bit shift (logical or arithmetic), the Base-10 result is equivalent to the floor of the original integer divided by 2. For example, if we had the number \(01010101_{2}\) (\(85_{10}\)) and we performed a right shift operation, then the result is \(00101010_{2}\) (\(42_{10}\)). Notice how the result is floor of the original Base-10 value divided by 2.

Aside: If we shift by multiple bits, then we are multiplying or dividing the original value by \(2^n\) where n is the number of digits we shift by. For example, if we had the number \(01100110_{2}\) (\(102_{10}\)) and performed a right shift by 3 bits, the result would be \(00001100_{2}\) {\(12_{10}\)} (we are dividing by 8 in this case). To break it down further: \(102/(2^3)\) –> \(102/8\) –> \(12.75\) which is \(12_{10}\) rounded down (or floored).

As mentioned in the above section, our ALU will contain the logic to perform a shift left operation (since logical and arithmetic shift left work the same way, we are just going to call it shift left). In order to do so, let’s revisit some of the key ideas of how a shift left operation works:

- The first key idea is that the LSB will be replaced by a 0.

- Every bit will move to the left by 1.

- The MSB will be removed. Now, that we understand those three key principles, let’s break down how to build the circuit.

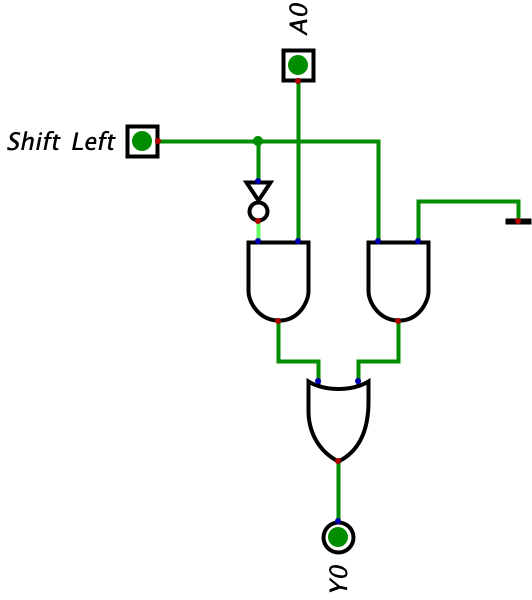

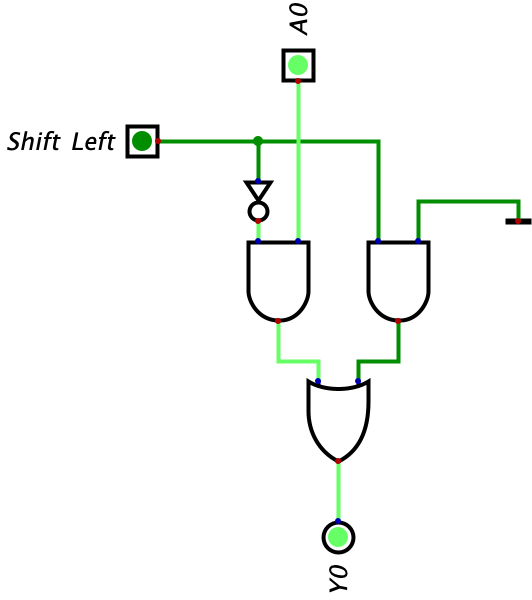

Let’s first take the example of how to shift 1-bit to the left. Keep in mind, no one in the computer science world really cares about shifting 1 bit to the left and you might be thinking this is a bit silly too, but for our purposes, you will see how starting with this example can be helpful. Going back to our example, if the bit value is 0 and we shift left, nothing will happen. But, if the bit value is 1 and we shift left, we want to replace it with a 0. Below, we will build a simple circuit to help us get started:

For the input \(A_{0}=1\), let’s look at the output when Shift Left is off and when Shift Left is on.

Let’s break this circuit down and think about this intuitively:

- The first thing that I would like to point out is the output is the result of two AND gates OR’d together.

- The right AND gate takes the input of the bit to it’s right (which is GND or 0 in this case) and the Shift Left input. The left AND gate takes the input of the corresponding input bit (A0) and the inverted value of the Shift Left input. Essentially, the right AND gate is responsible for calculating the result bit when we are shifting left and the left AND gate is responsible for calculating the result bit when we are not shifting left. At any given time, only one of the AND gates will be working and feeding input through (since one AND gate will receive a negated Shift Left input causing it not work). This means the OR gate simply passes on the result of the AND gate that is function to the output. Think about it for a second.

- When the Shift Left bit is off, the right AND gate will automatically be turned off since it receives no signal to one of its inputs. However, the left AND gate will be on since we are feeding it the opposite value of the Shift Left bit (in this case, since Shift Left is off, it will be fed a positive input). This means the result of the AND gate will be whatever input we feed through A0.

- When the Shift Left bit is on, the left AND gate will automatically be turned off since it is fed the inverted value of the Shift Left input (in this case, since Shift Left is on, it will be fed a negative input). However, the right AND gate will be on. This means the result of the AND gate will be whatever input we feed it which is GND or 0 in this case. So when the Shift Left bit is on, we are going to get a value of 0.

- Again, the OR gate simply acts as a way of passing on the input. It always receives a 0 as one of the inputs since one of the AND gates feeding into will always be off. However, the result of the other AND gate will be passed through enabling us to read it. Without the OR gate, we don’t have a way of reading the output of the AND gates since there are 2 outputs and we wouldn’t know which one contains the information we need.

- The right AND gate takes the input of the bit to it’s right (which is GND or 0 in this case) and the Shift Left input. The left AND gate takes the input of the corresponding input bit (A0) and the inverted value of the Shift Left input. Essentially, the right AND gate is responsible for calculating the result bit when we are shifting left and the left AND gate is responsible for calculating the result bit when we are not shifting left. At any given time, only one of the AND gates will be working and feeding input through (since one AND gate will receive a negated Shift Left input causing it not work). This means the OR gate simply passes on the result of the AND gate that is function to the output. Think about it for a second.

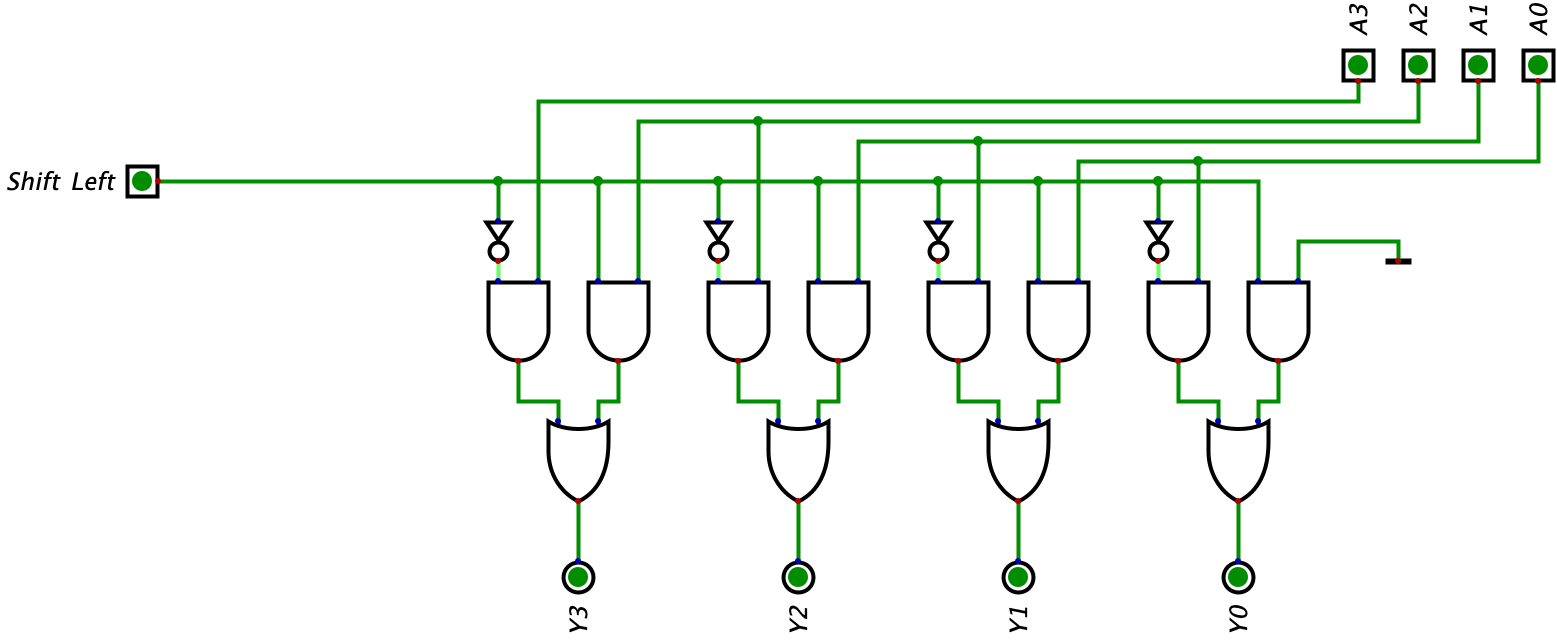

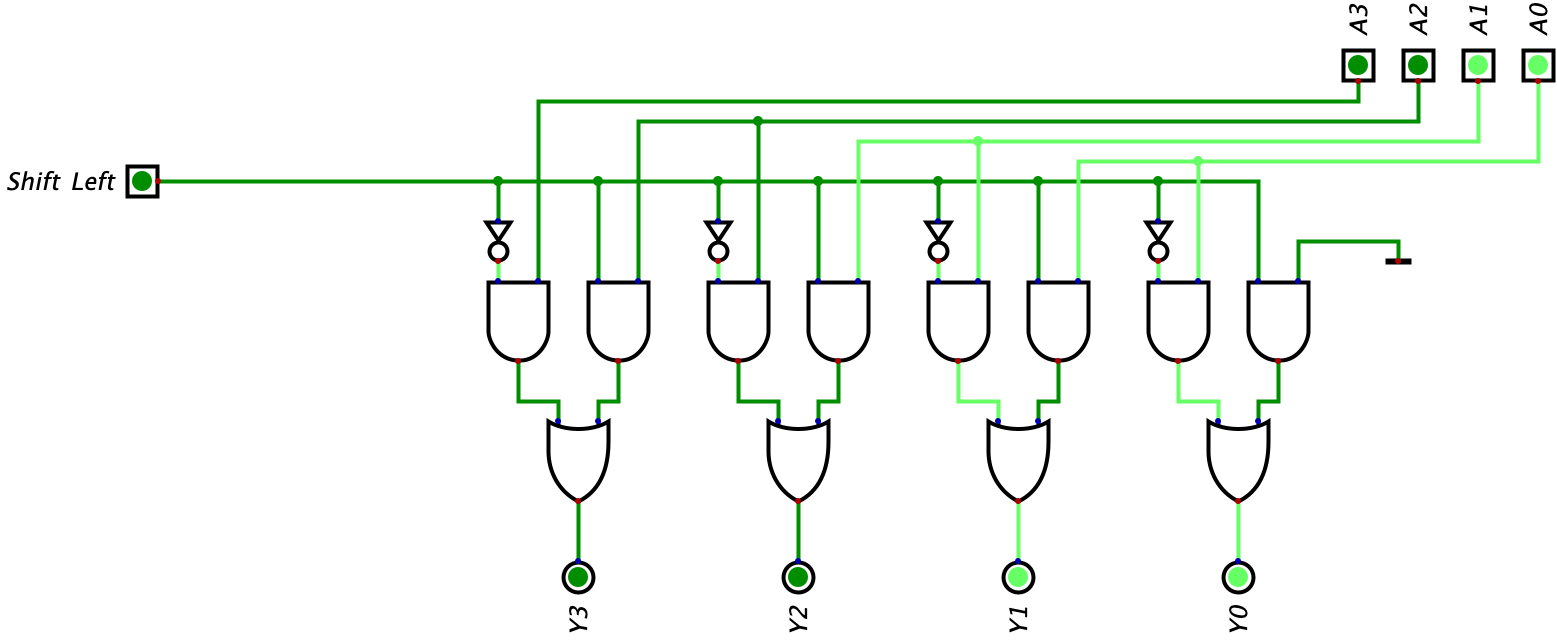

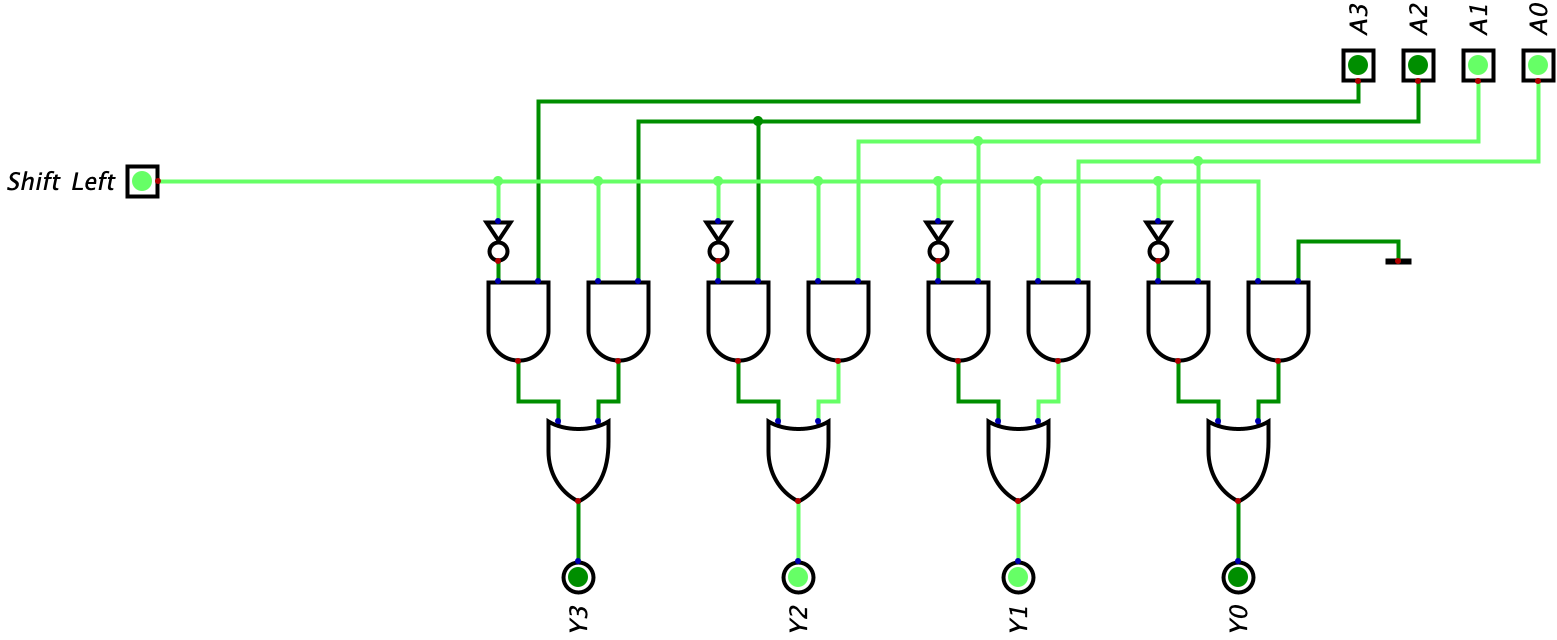

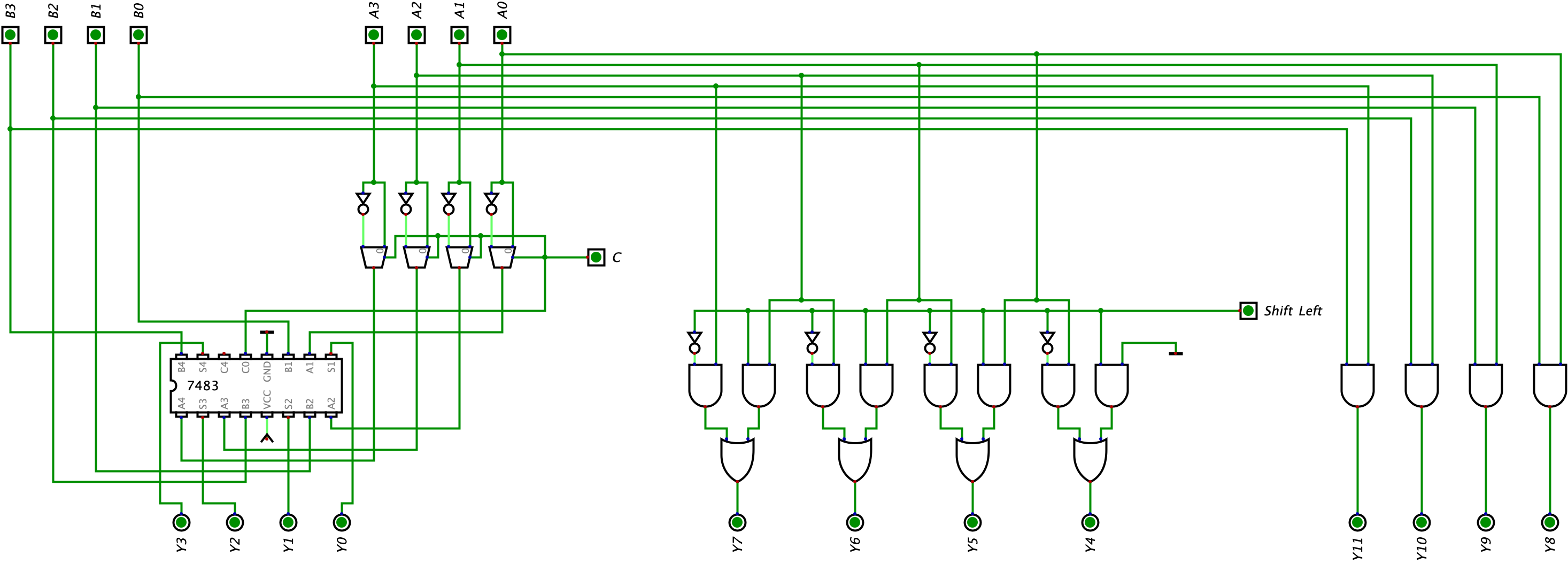

We can now expand on this circuit and build a 4-bit shifter. We can copy the above logic for each bit position. However, the only thing that will change is instead of feeding the GND input to the right AND gate, we can feed it the value of the bit position to its right (this only applies to non-LSB position since the LSB is replaced by a 0 during a shift left operation). Below we have the completed 4-bit left shifter:

Now here is an example of the circuit with the input being \(0011_{2}\) (one image shows the Shift Left input being off and another image shows the Shift left being on):

4-bit ALU

Building the ALU Logic

As you can tell, the ALU has many different parts to it, so we are going to build it one step at a time. In this section, we are going to build a 4-bit ALU. Again, our ALU is going to be responsible for 4 different things: adding, subtracting, performing AND logic, and performing shift left operations (the latter two are operations we learned above).

The first step in building this 4-bit ALU is of course building out some of the logic, and you might be asking yourself where we can start. Well, in the last chapter, we spent a fair amount of time discussing how to build an Adder-Subtractor circuit. Technically speaking, the Adder-Subtractor is a simple ALU itself because you feed in the two operands you want to perform arithmetic on, an opcode (0 for addition and 1 for subtraction), and receive an output based on the opcode we feed it. However, an ALU can be much more than an Adder-Subtractor circuit and the main purpose of this chapter is to understand that and how the logic actually flows through an ALU.

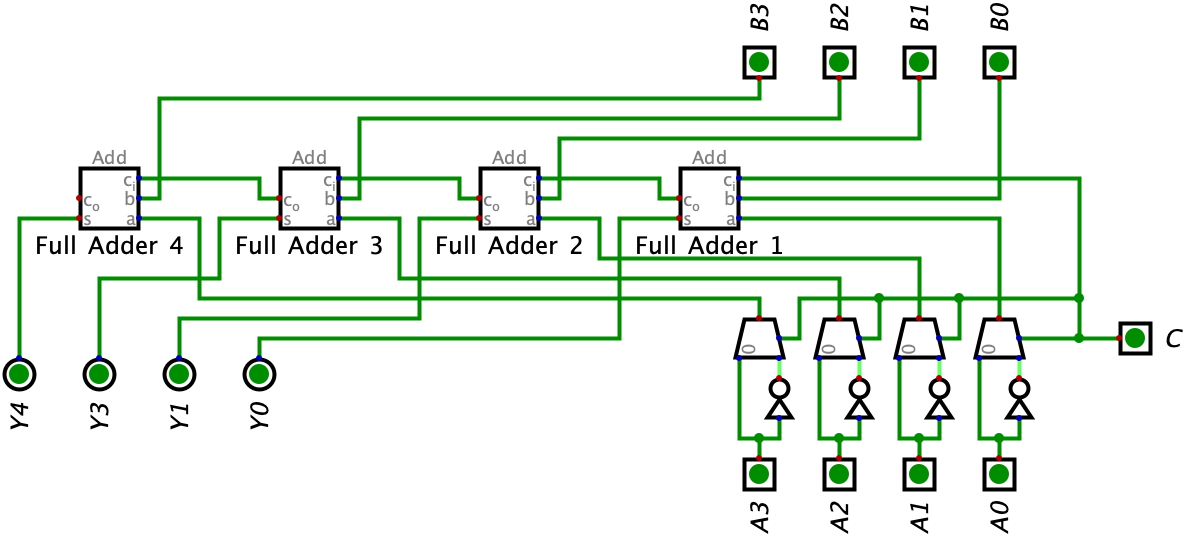

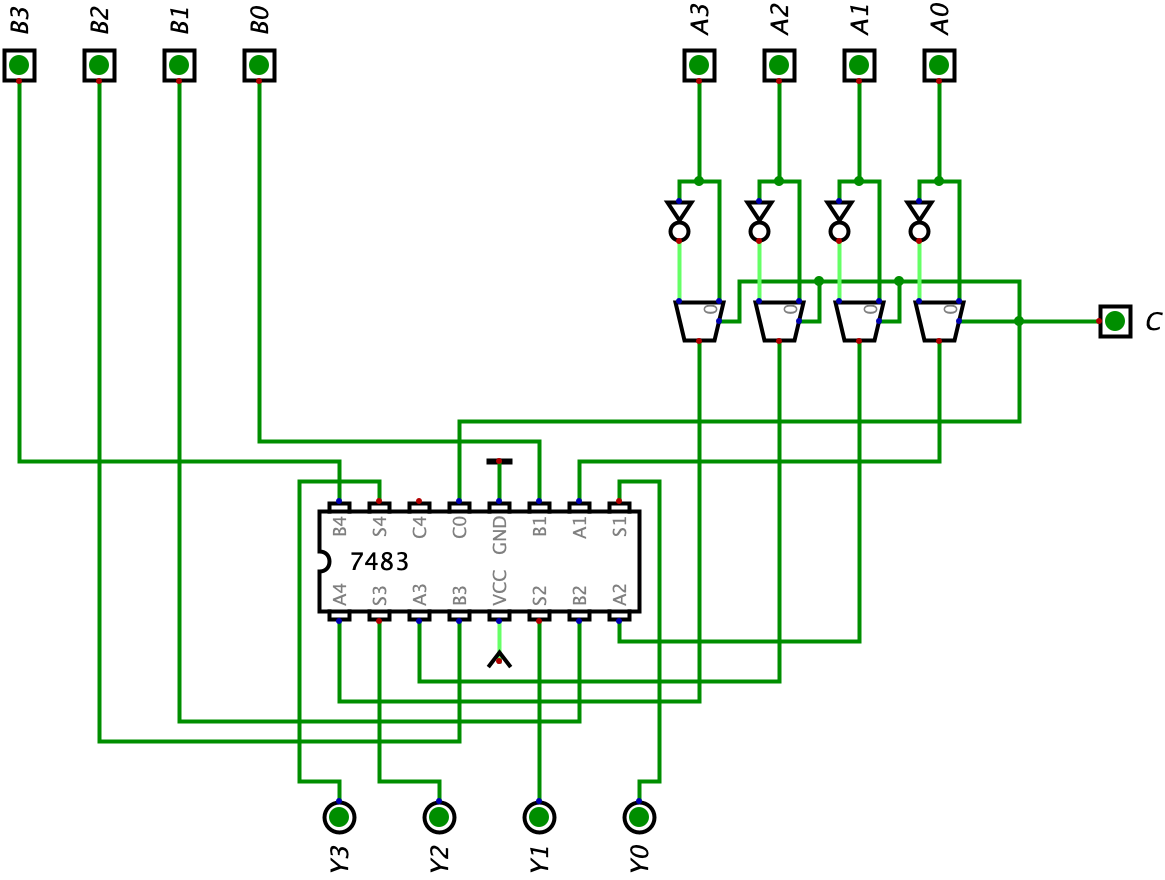

Let’s go ahead and copy our Adder-Subtractor logic from Chapter 8 and start building out this ALU:

Again, notice how we already use an opcode for the ALU (or Adder-Subtractor). The C bit can be used to toggle between addition and subtraction.

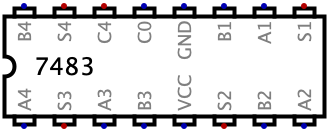

However, we can abstract this circuit further by using an Integrated Circuit (IC) which was introduced at the end of Chapter 6. We will be using a 7483 IC which is a 4-bit binary full adder (otherwise known as a Ripple Carry Adder which we studied last chapter) which is displayed below:

This IC has multiple inputs/outputs, let me quickly describe what each does to you. The A1, A2, A3, A4 inputs are for responsible for receiving the A input; the B1, B2, B3, B4 inputs are responsible for receiving the B input; the S1, S2, S3, S4 are responsible for outputting the sum of the addition/subtraction; C4 is the final carry-out; C0 is the initial carry-in (to signal whether we are performing addition or subtraction); and the VCC and GND are the power and ground respectively (you will see every IC requires VCC and GND inputs in order to properly power the circuit).

We can use the 7483 IC to build an Adder-Subtractor by using the same logic we used to transform a Ripple Carry Adder to an Adder-Subtractor - use the C bit to add 1 to the circuit and flip all the bits of the subtrahend with the help of the multiplexor. Here is our ALU so far:

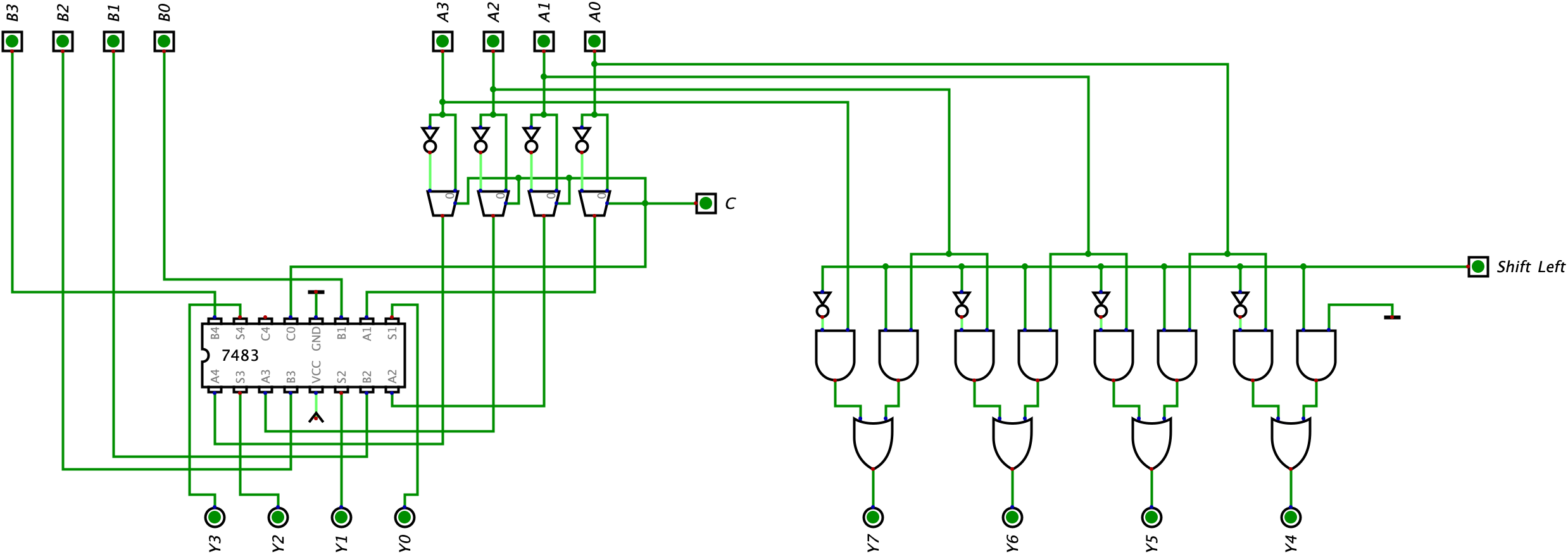

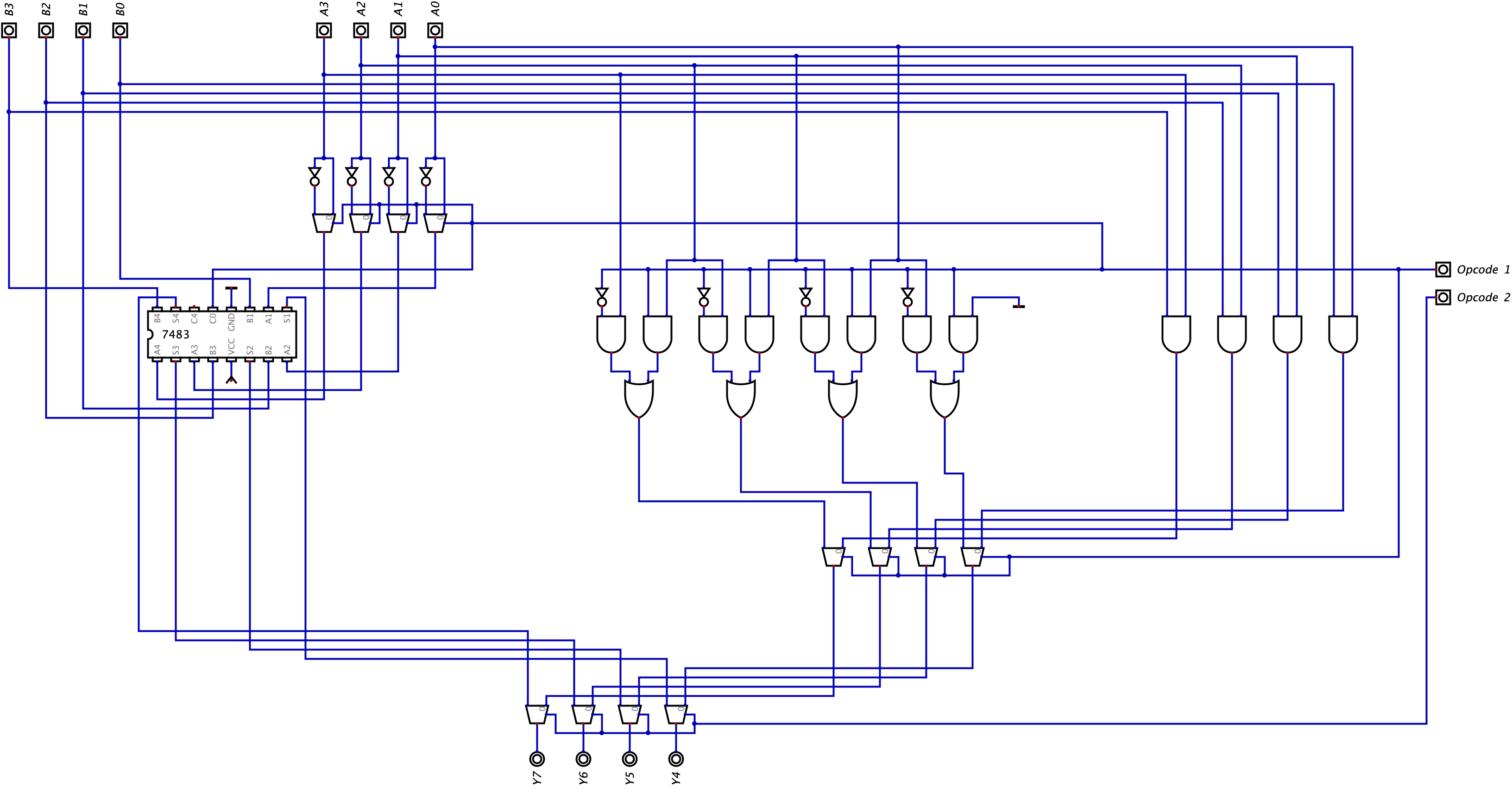

Next, we can add in our logic for shifting left. We can copy the circuit which we build in the previous section for shifting left and add it to our ALU so our ALU will perform a shift left operation on Input A simultaneously (don’t worry about the opcode just yet). Here is our updated circuit:

In the circuit above, the ALU will perform addition/subtraction and a shift left operation on Input A. Below is an example of the ALU receiving two random inputs for Input A and Input B. The first image shows an example with the Shift Left bit turned off (meaning we do not perform any shifting) and the second image shows an example with the Shift Left bit turned on (which means shifting is performed). I will let you confirm the given logic in both of the images below as a challenge.

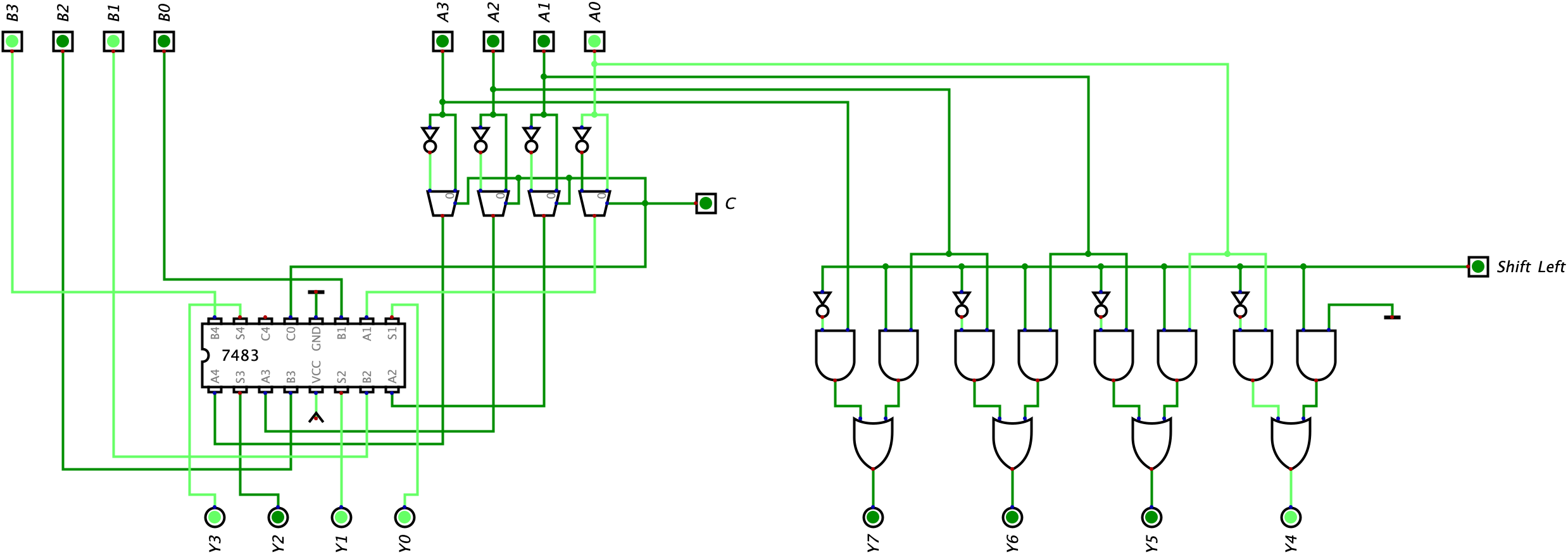

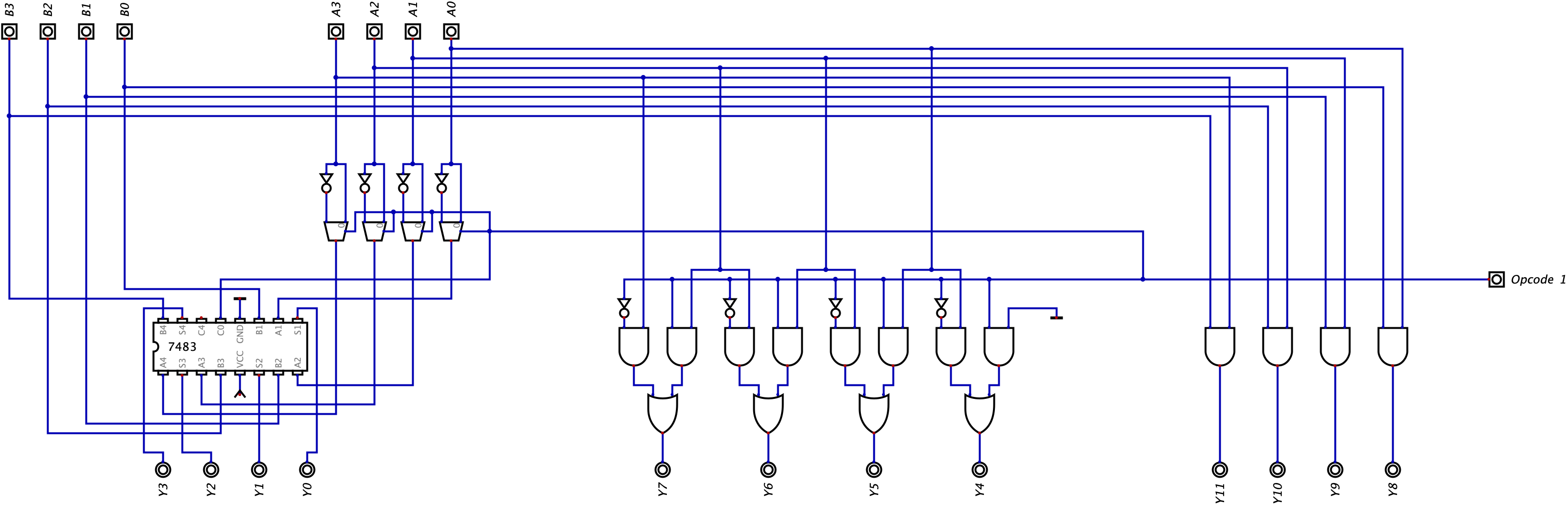

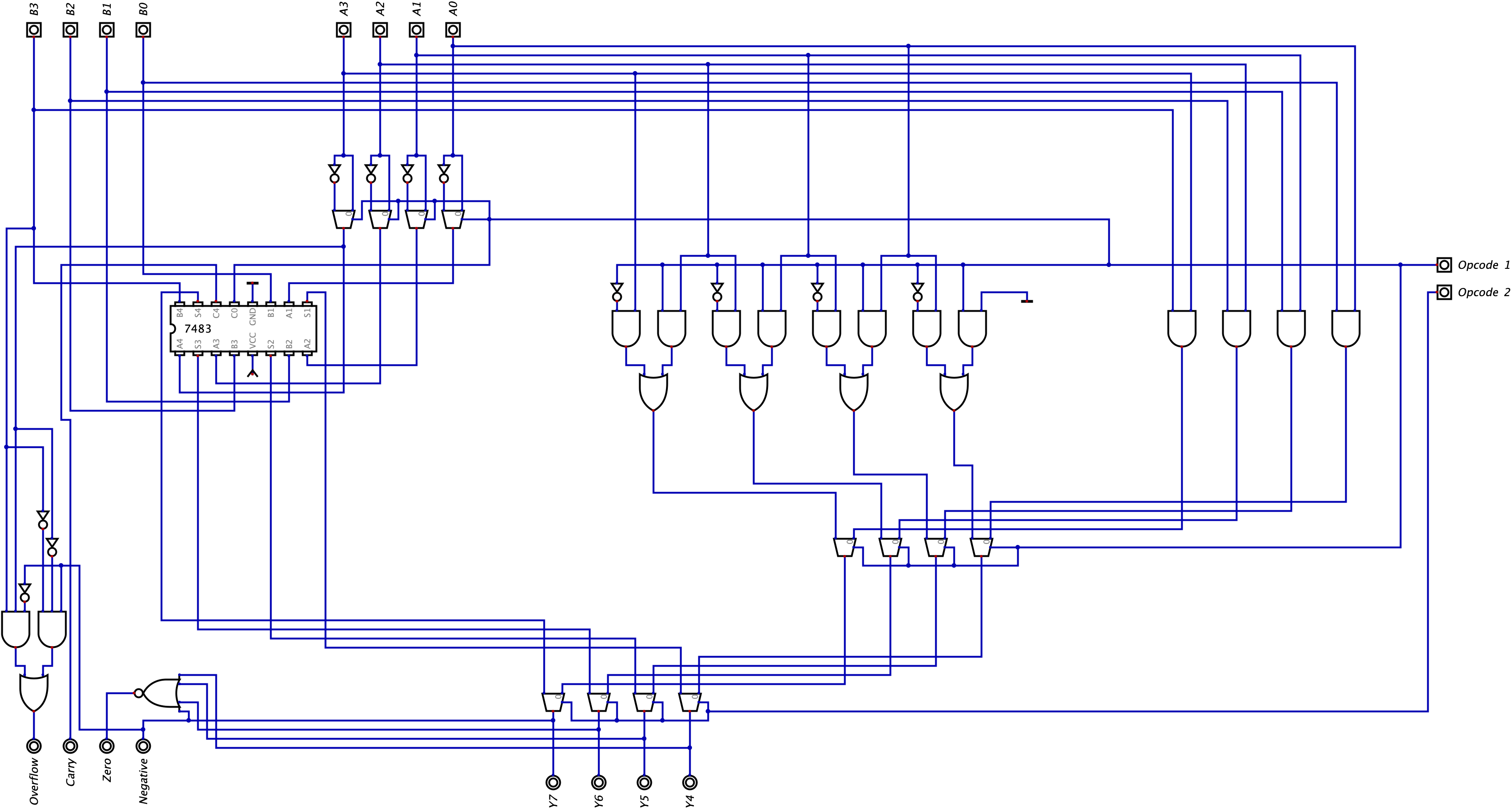

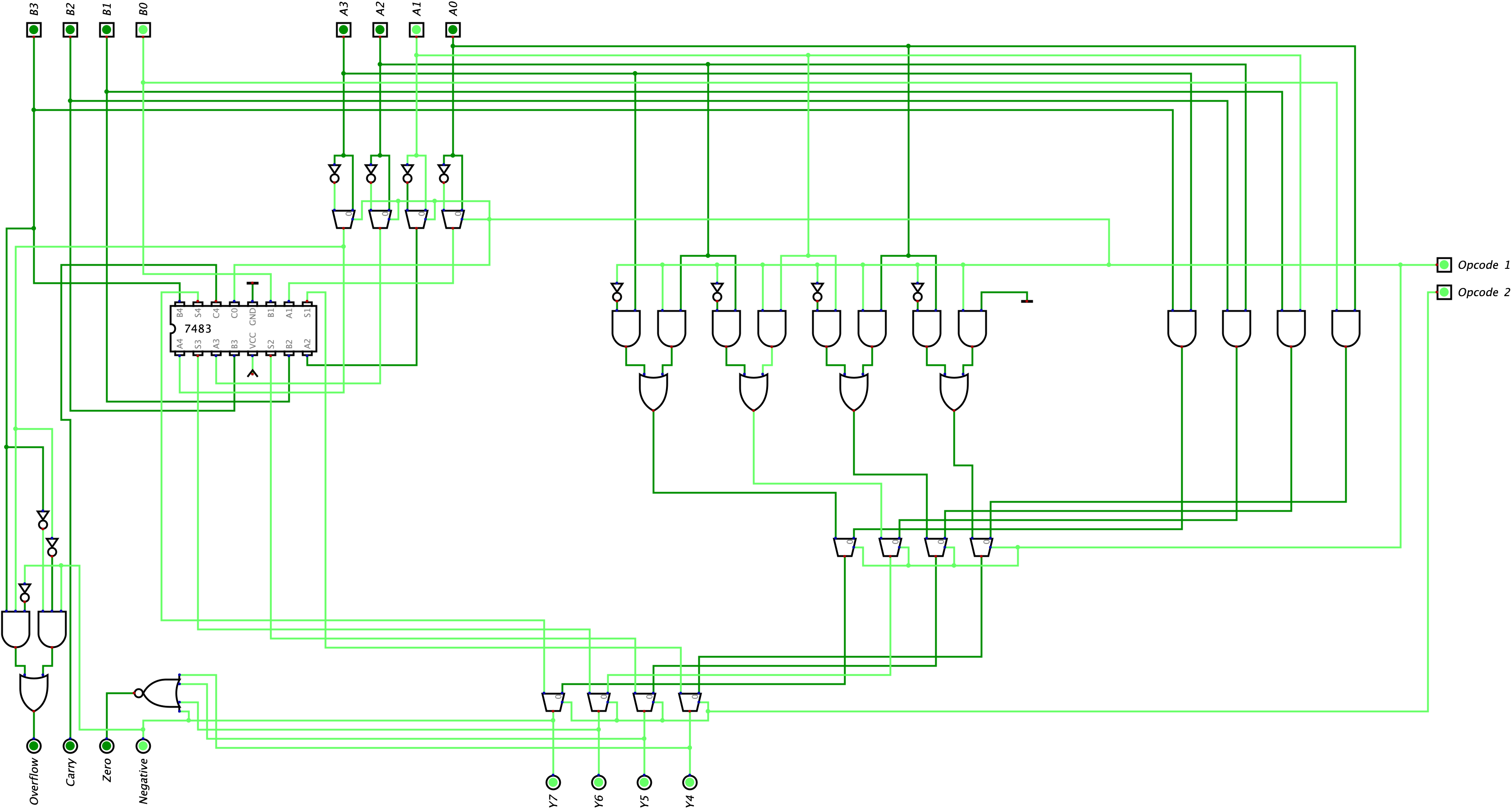

Finally, we will add the last logical component to our ALU: the bitwise AND logic. In the circuit below, we do the same thing we did for the shift left logic. We are going to add the bitwise AND logic and the ALU will simultaneously calculate an output for Inputs A and B while also calculating an output for the addition/subtraction logic and shift left logic. Here is our circuit with the added bitwise logic:

Using Operands to Select Output

Now that we have all the logical components of our ALU in place, it is time to understand how the ALU chooses the correct output based on the operand we provide. In any given scenario, the ALU will be given two operands, it will calculate the output as shown in the image for all of the possible scenarios, and then we provide the ALU another input, called the opcode, to select the output we desire based on what operation we want the ALU to complete. So if we wanted the ALU to perform the bitwise AND operation, the ALU will also complete calculations for adding/subtracting and the bitwise XOR operation, and based on the operands provided, it will select the result of the bitwise AND operation. You’re probably asking what is the purpose of doing all the calculations if we just select the result of one of them at the end. In our situation, we are just trying to demonstrate what the ALU is doing without the thought of efficiency to keep it as simple as possible for now (modern computers are much more efficient).

Your other burning question also might be how to implement this. Well, it turns out we are going to be using multiplexors again (surprise). The first thing that we want to do to modify our ALU is make the C bit and Shift Left bit the same. What this essentially means is that there will be one bit to control both of these operations. If we shifting left, we are also doing subtraction and if we do subtraction, we are shifting left. We are going to rename this bit to Opcode 1. Let’s check out our circuit below:

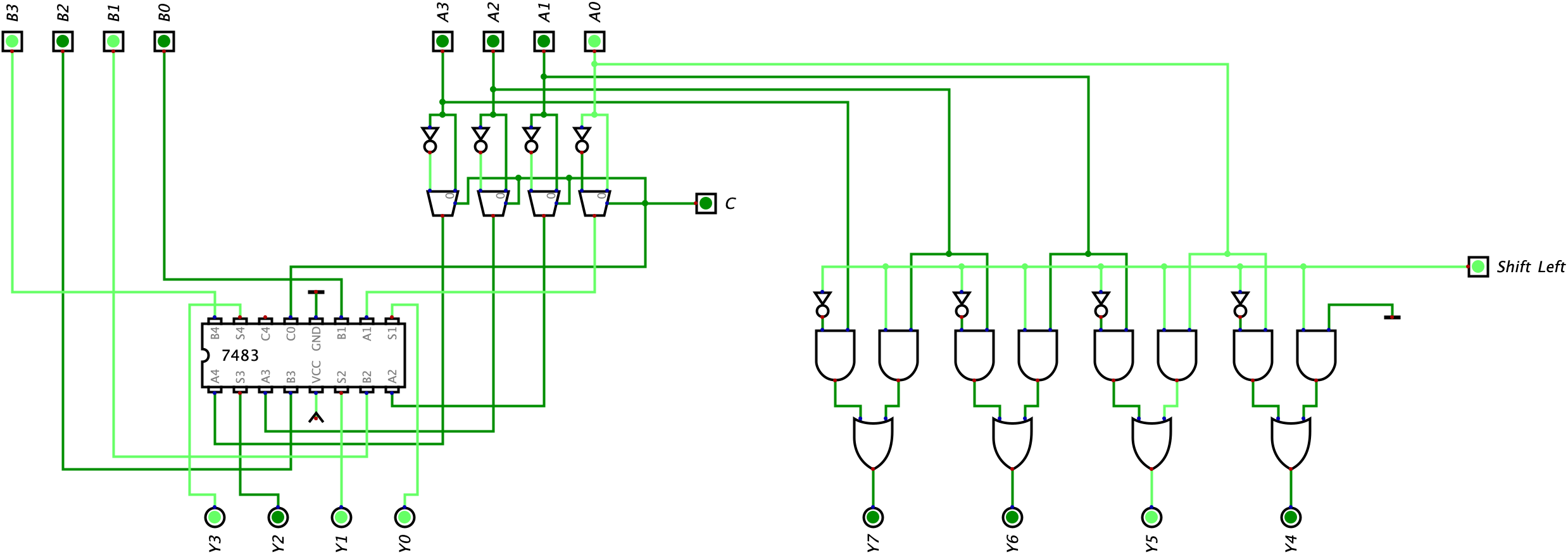

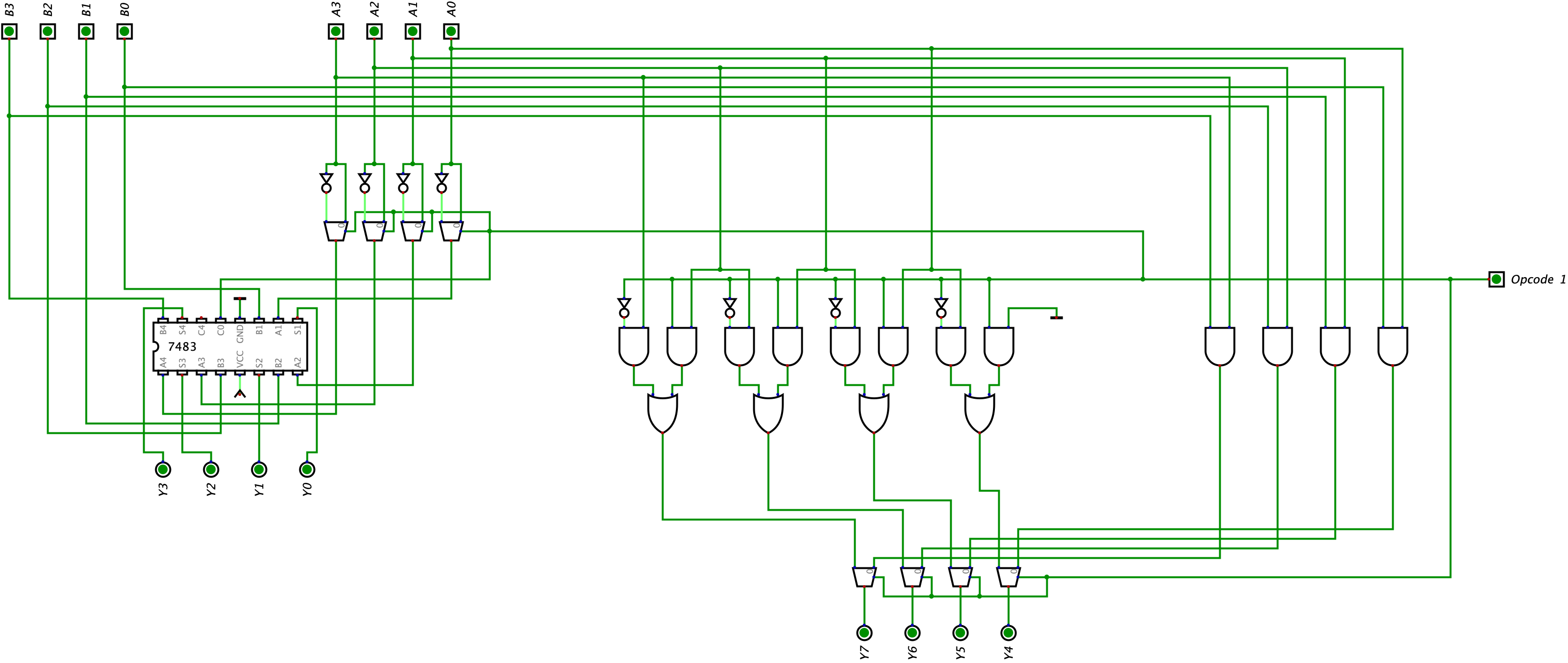

Remember earlier when I mentioned that we would start choosing the outputs based on the opcode and use multiplexors to do so, well now we can implement them. This won’t make much sense at first, but bear with me. We can break our current ALU down into 2 halves. The left half being the Adder-Subtractor which already returns us 1 singular output whether we are doing addition or subtraction. The right half of our ALU is responsible for the bitwise AND logic and shift left logic which returns us 2 outputs. Here, we need to filter logic further for the right half of our circuit to only return 1 output. We can first use a set of multiplexors to choose between the results of the shift left operation and the bitwise AND operation. To be exact, we need 4 multiplexors since each portion or logic returns a 4-bit result. We can feed these multiplexors the value of Opcode 1 (which we created in the previous paragraph) to choose between the bitwise AND logic and shift left logic. Let’s look at our updated circuit:

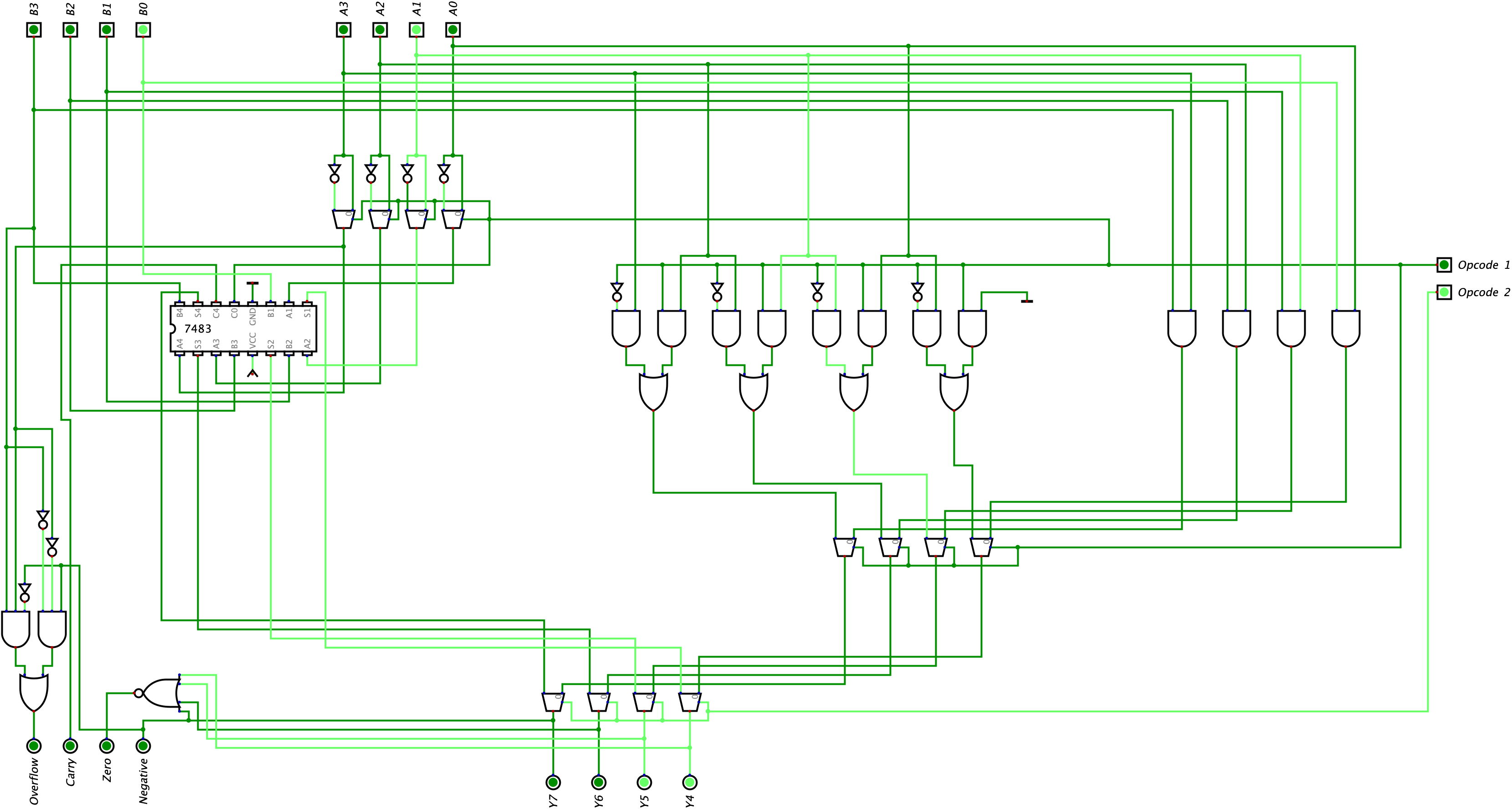

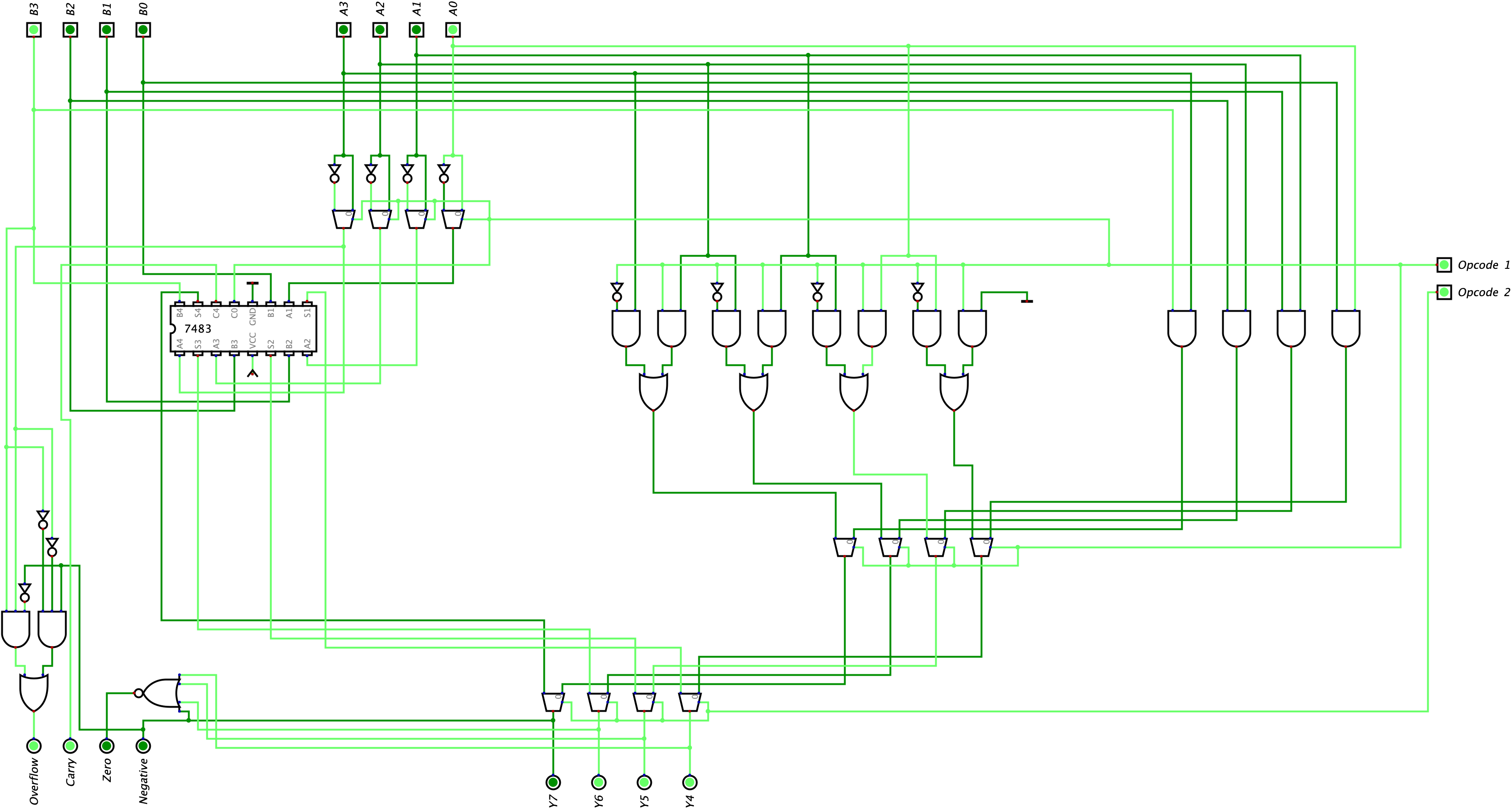

I hope looking at the circuit is making more sense. We are essentially choosing the output of the ALU based on the opcode we provide. Notice how we still have the 2 seperate results (the Adder-Subtractor result and the result between the Shift Left logic and bitwise AND). We can create another opcode and set of multiplexors to filter this result.

However, before we create another opcode value, I want to take the time to explain why we can’t use the same opcode for those of you wondering. Here is an image of the ALU which feeds in the same opcode (Opcode 1) into the new set of multiplexors (for example purpose - this is incorrect as explained in the paragraph below):

Right now, we have 4 different operations we can choose from - addition, subtraction, bitwise AND, shift left. Let’s say set Opcode 1 to 0. On the left half of the ALU, our Adder-Subtractor will perform addition. On the right half of the ALU, our ALU will need to choose the result the shift left logic outputs or the result the bitwise AND outputs. Since Opcode 1 is set to 0, we can see from the image above, the ALU will choose the bitwise AND logic to select. If we had another set of multiplexors to now choose between the left and right side and were feeding in the same opcode (Opcode 1), take a second to hypothesize what would be outputted. If you said the bitwise AND logic would be outputted, you’re right.

Now, let’s flip the value of Opcode 1 to 1. In this case, our Adder-Subtractor will perform subtraction. On the right half of the ALU, our ALU will perform a shift left operation (since Opcode 1 is also being fed in as the Shift Left bit) and the multiplexors will choose the result of the shift left operation. Then, in the second level of multiplexors, we now need to choose between the subtraction and the shift left and since Opcode 1 is 1, we will be choosing the result of the subtraction logic.

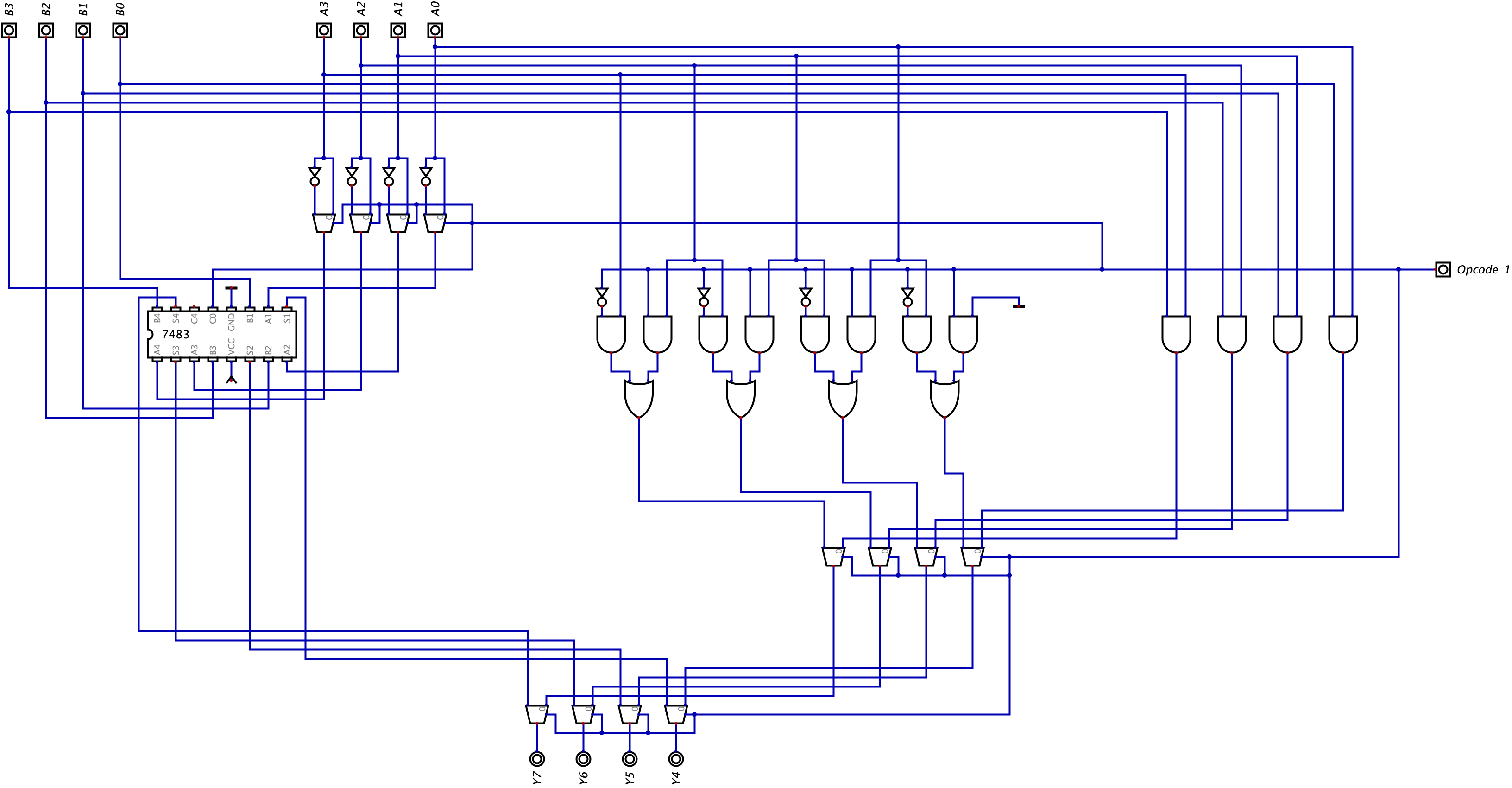

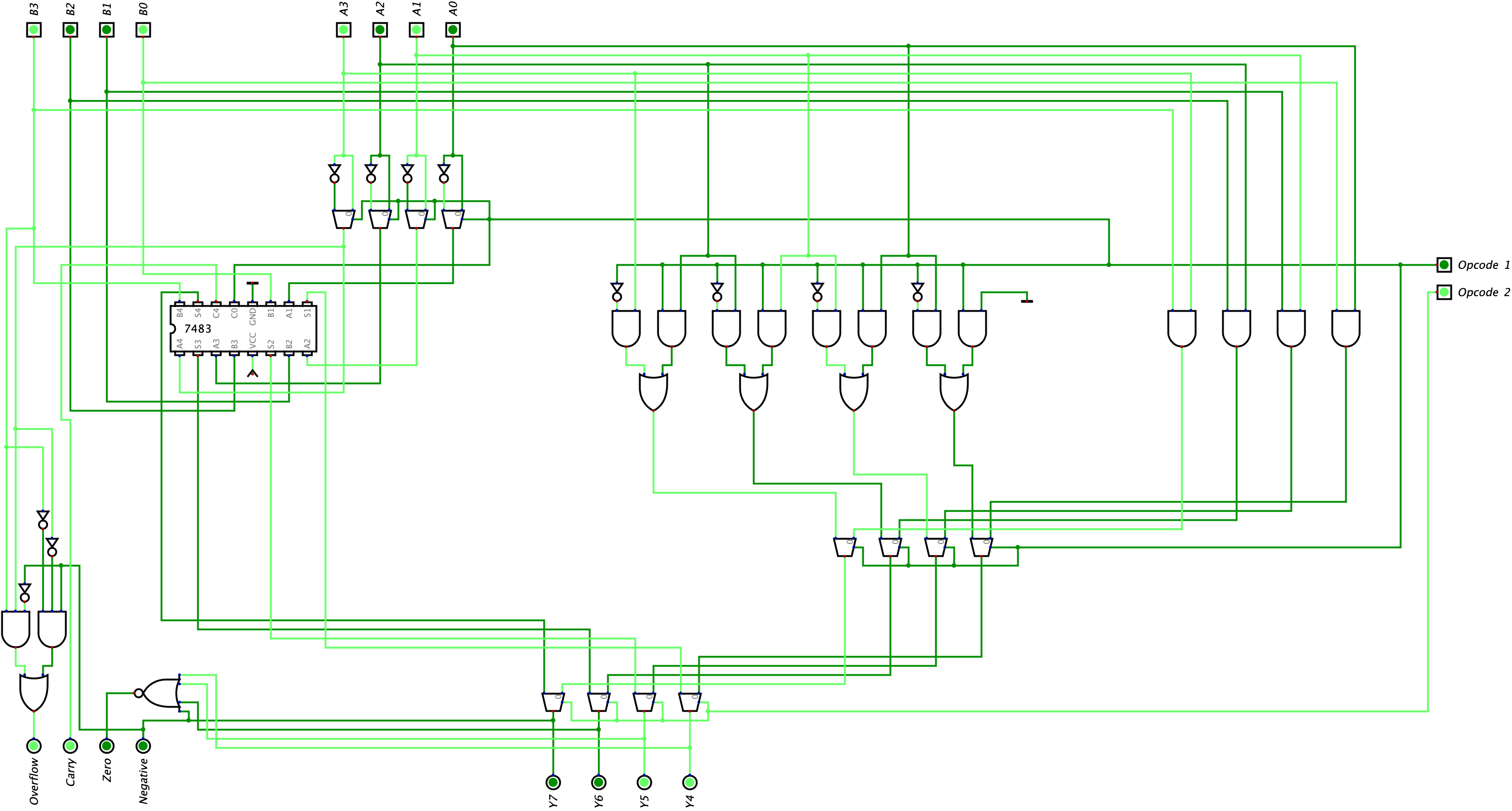

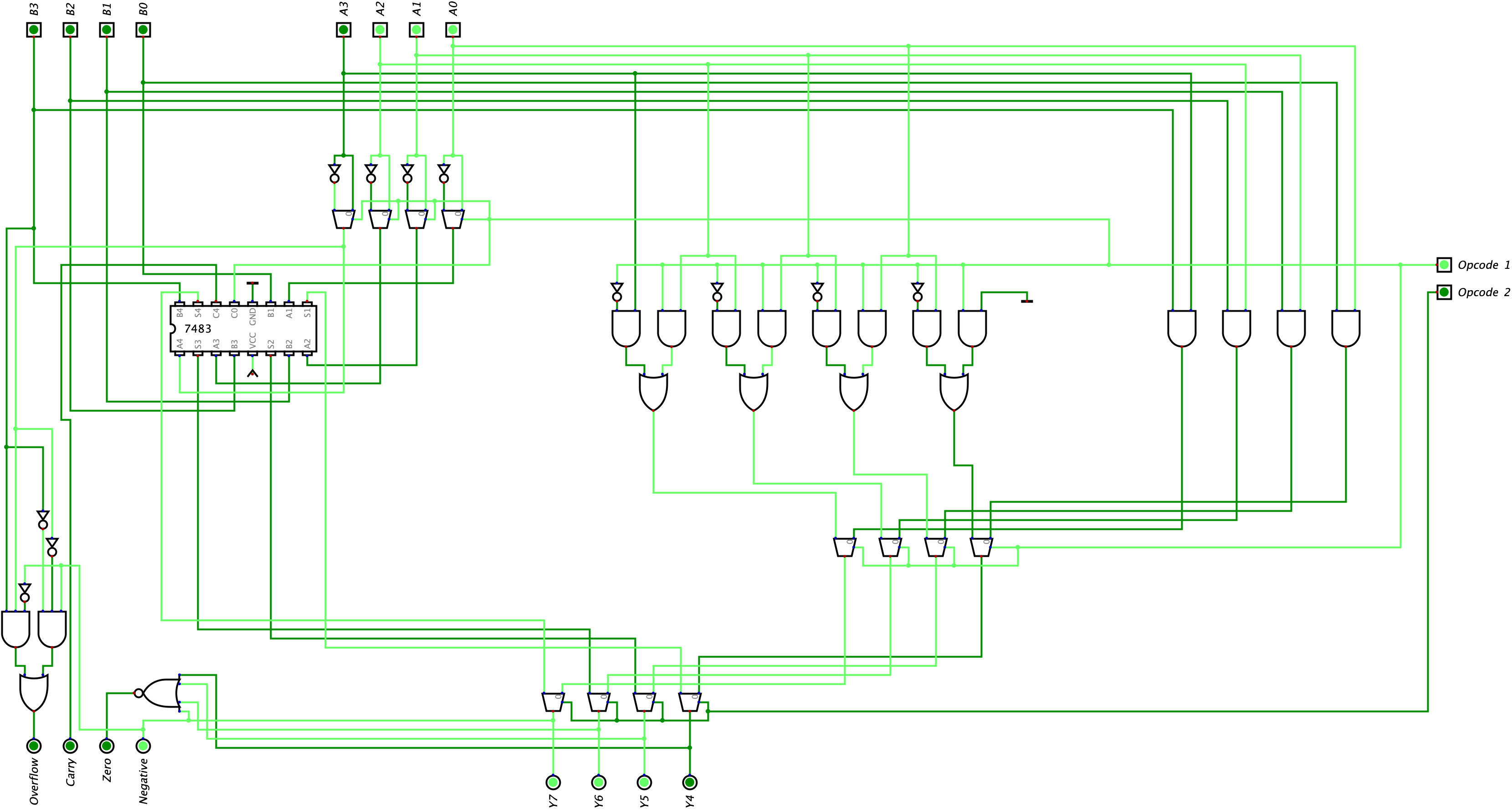

As you can see, when we only use one opcode bit, we can choose between two operations only (which was previously mentioned in the beginning of the chapter and is demonstrated in our Adder-Subtractor circuit). This is why we need to create another opcode bit to feed into the next level of multiplexors to choose a result between the left half of the ALU and right half of the ALU. Below we create another opcode bit and feed it into the second level of multiplexors:

Essentially, we can demonstrate in a table what operations will be performed based on the opcode chosen:

| Operation Performed | Operand 1 | Operand 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Bitwise AND | 0 | 0 |

| Shift Left | 1 | 0 |

| Addition | 0 | 1 |

| Subtraction | 1 | 1 |

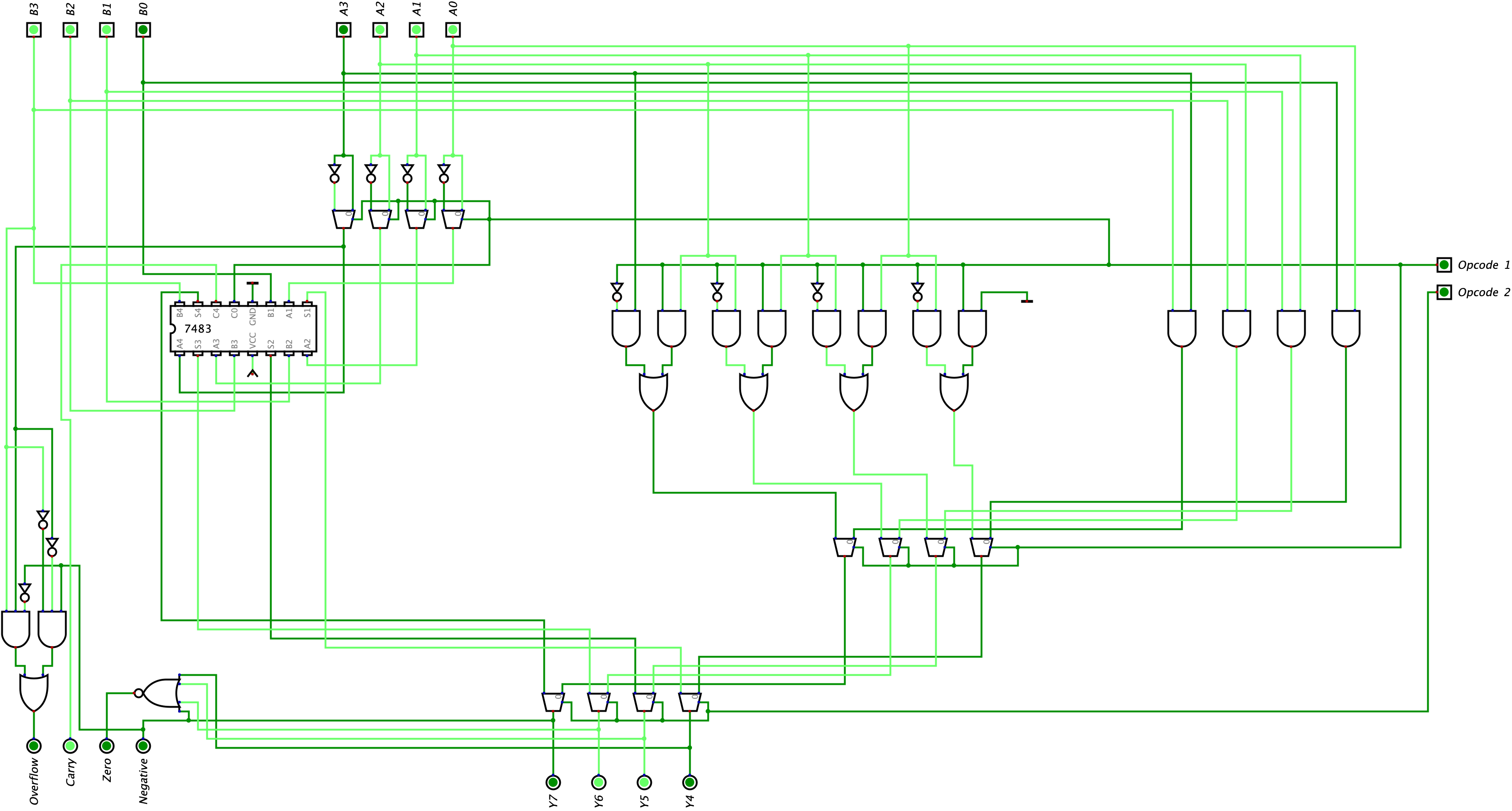

Output and Flags

The last part to building our ALU is creating the flags: carry, overflow, zero, negative. Here is how we build each one of these flags:

- Negative: This indicates whether our result was negative and we can use the MSB (Y3) to toggle this flag.

- Zero: This indicates whether the result is 0 and is an NOR gate. This makes sense because we want all of the bits to be turned off and the output of an inverted OR gate will only ever be on if all the inputs are off.

- Carry: This indicates if we have an overflow when doing unsigned arithmetic and is just the ouput of C4 from the 7483 IC we use. In the previous chapter, I claimed we could only feed two’s complement numbers as the operands into our ALU when doing addition and subtraction. However, we can also perform unsigned addition with our ALU. Remember the Adder-Subtractor we built is technically a Ripple Carry Adder, so it is possible to do unsigned addition which is why we include the Carry flag.

- Overflow: This indicates if we have an overflow when doing signed arithmetic (with two’s complement). The logic behind this flag was explained in the previous chapter.

Here is our finished ALU below:

Examples

Below, we are going to display some examples of the ALU performing calculations. My challenge to you is to take your time and trace through these circuits. Try to download the .dig file also and come up with your own examples.

In our first example, we will be doing addition where Input A is \(0010_{2}\) and Input B is \(0001_{2}\). Here is our circuit below:

In our second example, we will be doing addition which results in overflow where Input A is \(1010_{2}\) and Input B is $10001_{2}$$. Here is our circuit below:

In our third example, we will be performing subtraction where Input A is \(0010_{2}\) and Input B is \(0001_{2}\). Here is our circuit below:

In our fourth example, we will be performing subtraction which results in overflow where Input A is $0001_{2}\(and Input B is $1000_{2}\). Here is our circuit below:

In our next example, we will be performing a shift left operation on Input A where Input A is \(0111_{2}\). Here is our circuit below:

In our final example, we will be performing bitwise AND logic where Input A is \(1110_{2}\) and Input B is \(0111_{2}\). Here is our circuit below:

Congrats! We finished building our 4-bit ALU. I highly encourage you to download the Digital file and play around with the ALU to ensure you really understand how it works. Try modifying it too! In the later sections, we are going to be looking at and building some more components which are important to how a computer processes and stores information.