Let's Understand How a CPU Works

Designing a CPU from the ground up, with no knowledge needed

Chapter 07 - Addition with Logic Gates

Topics Covered: Half Adder, Full Adder

Now that we have learned about logic gates, I think it’s time we learned why they are so important (hopefully, the not so boring part). As mentioned in Chapter 6 briefly, logic gates are the building blocks of computers and when you chain logic gates together to build circuits, you can essentially build a computer. That being said, we move onto the next step of our journey - building circuits. In Chapter 6, we skimmed over the definition of a logic circuit. In computer science, a circuit allows us to represent more complex logic beyond the basic AND and OR gates and allows us to transform our binary inputs into the outputs we desire. An easier way to think about this is by using legos. In Chapter 6, we got introduced to the brick blocks, the tile blocks, the plate blocks, etc. Now, it’s time for us to take those different lego pieces and build our first circuit.

Representing Addition Using Logic Circuits

In the earliest chapters we were introduced to idea of Base-2 and learned how to add two binary numbers together (signed and unsigned). In this chapter, let’s automate this process by designing a circuit that can add two binary numbers together. I just want to make a quick note by stating that you can build a circuit to do a lot of different things. But, we are going to start out by building circuits that add binary values together for two reasons. First, if you take any computer science degree, most classes are going to start from the ground up just like we did with addition in kindergarden and first grade and work their way up in difficulty. And the second reason is in early computing, most computers were built to serve basic needs such as solving arithmetic problems. So, I think it would be helpful to follow this course and then build up our knowledge.

Aside: Keep in mind that all the addition we do in this chapter and the following chapters will be unsigned until I mention that we are using signed addition.

You already know that computers can add incredibly large numbers together, but for the sake of us getting started, we will restrict our circuit to adding two 1-bit values (recall that a bit is a binary digit), namely A and B. Let’s take an example below as a first contender of a circuit that takes 1-bit values A and B as input and outputs their sum (\(A+B\)) as Y:

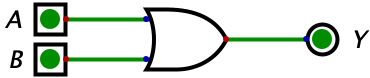

Above we have a circuit representing the equation \(A+B=Y\). Essentially, this circuit adds two numbers together (in this case, \(0_{2}\) and \(0_{2}\)) and outputs a number (which again is \(0_{2}\)). In other words, our equation can be represented like this: \(0_{2}+0_{2}=0_{2}\). In this example, what we are trying to demonstrate is that the OR gate can be used to add two numbers together and is a simple addition circuit (which was mentioned in Chapter 6). Congrats, you just build your first circuit!

Let’s look at a slightly different example:

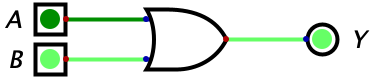

Here, we are adding \(0_{2}\) with the \(1_{2}\) which gives us \(1_{2}\). This equation can be written as \(0_{2}+1_{2}=1_{2}\). Makes sense right? I know I’m definetly boring you, so let’s look a slightly harder example:

Aside: If the above two examples are confusing, convert the Base-2 equations to Base-10 form and attempt to parse through the circuit using that logic. I would highly recommend going back to Chapters 3 and 6 if you are still having trouble.

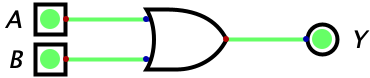

Here, we are adding \(1_{2}\) (\(1_{10}\)) and \(1_{2}\) (\(1_{10}\)) which gives us \(1_{2}\) (\(1_{10}\)). If you realized there’s a mistake here, you’re right. \(1_{10}+1_{10}\) should be returning \(2_{10}\). \(2_{10}\) is written as 10 in binary - notice how we need two bits. You might be thinking that there is no possible way we can represent \(2_{10}\) with our current circuit (which is an OR gate) since an OR gate can only ouput one bit. This is where things get exciting.

Half Adder

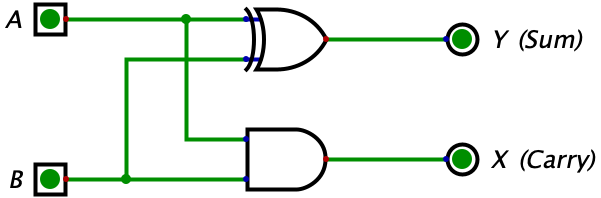

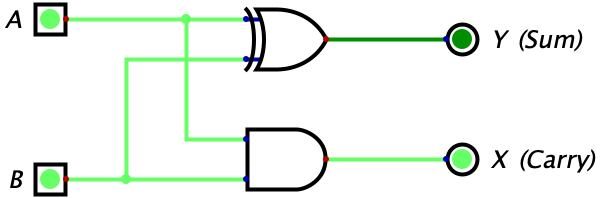

Remember when I was talking about legos earlier, this is where we use them. Just like how we can connect different legos with each other to build more complicated things, we can connect different logic gates to build more complicated circuits. Here is where we introduce the Half Adder:

The issue with using just an OR gate to represent the addition of two bits is that sometimes the bits can add up to \(2_{10}\) (which is represented by 2 binary bits) when we add \(1_{10}\) and \(1_{10}\) together which we saw in the example in the paragraph above. We need to build a circuit that outputs 2 bits instead of 1 bit when adding bits together. Essentially, we need a way to represent the equation \(1_{2}+1_{2}=10_{2}\).

This is where a half adder circuit is useful because we can now represent two bits in our output: the sum and carry-out digits (which was talked about in Chapter 3). When adding \(1_{10}\) and \(1_{10}\), the result will have a sum bit of \(0_{2}\) and carry-out bit of \(1_{2}\) (reference Chapter 3 if this does not make sense).

In the circuit above, the Y acts as the least significant bit (the sum bit) and the X acts as the most significant bit (the carry bit). We can combine the sum bit and carry bit in a singular output and represent this circuit in equation format as \(A_{2}+B_{2}=XY_{2}\).

Now, your question might be how did we know to use the XOR gate to calculate Y and the AND gate to calculate X? Take a look at this truth table below which represents the addition of two 1-bit binary values:

| A | B | Y (Sum) | X (Carry) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Aside: Before we go any further, we should note that these calculations are the same as the ones in Chapter 3.

First, looking at the Sum Column (Y Output), we can see that it looks pretty familar to one of the truth tables in Chapter 6. If you were thinking an XOR gate, then you’re right! And, looking at the Carry Column (X Output), we can see that the output looks similar to an AND gate. Now we can see why the half adder uses a XOR gate and an AND gate instead of using a normal OR gate.

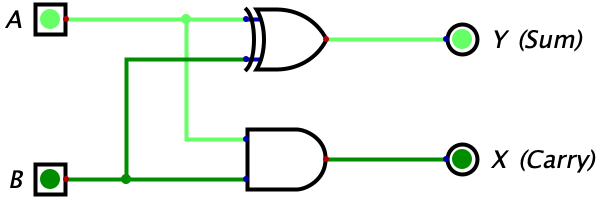

All the possible combinations of adding 2 1-bit values can now be represented using a Half Adder. The equation \(1_{2}+1_{2}=10_{2}\) is shown in circuit form below:

Here is another example of using a half adder for the equation \(1_{2}+0_{2}=01_{2}\):

In this example, we can see that the output is \(01_{2}\). Again, the Y (sum bit) is used as the least significant bit and the X (carry-out bit) is used as the most significant bit.

What you should take away from this section is that the Half Adder circuit allows us to represent more complicated addition which involve carry-overs.

Full Adder

Remember how we were talking about lego bricks earlier? Well, you might hate me, but we are going to add another brick on top of our current circuit. Let’s say we want to add another input to our circuit and call it the carry-in bit (I will explain why this bit is so important in Chapter 8, so hang tight). So now we want to add the A, B, and C (carry-in) bits together to output a sum bit (Y) and a carry-out bit (X), so the equation we are now trying to build our circuit for can be represented by \(A_{2}+B_{2}+C_{2}=XY_{2}\). Let’s take a look at the truth table and build the full adder circuit (again, this truth table is a representation of adding 3 1-bit values and their ouputs):

| A | B | C | Y (Sum) | X (Carry Out) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Aside: If the above truth table is still confusing, think about it this way. Again, the equation we are trying to represent with the truth table and circuit is \(A_{2}+B_{2}+C_{2}=XY_{2}\). If we add any row of values together, such as the last one where all the inputs are equal to \(1_{2}\), then an easy trick we can do to find the output is convert all the inputs to numbers (which in this case are all equal to \(1_{10}\)), add them (the result being \(3_{10}\)), and then convert them back to binary (which gives us \(11_{2}\)).

Next, we are going to use the SOP trick we learned in Chapter 6 to construct and simplify an expression for the truth table above. If you want to skip this part, feel free (the equations are provided below the optional section). I only included this part if you wanted to go over another SOP example (as long as you understand that you can take the ouput of a truth table, convert it to a boolean expression, and then use that expression to build a circuit, you understand the basis of how to build a logical circuit).

Aside: For the Half Adder, we were able to quickly identify which logic gates to use because that was a simpler example, so we could visually make that connection. Usually to build logic circuits, we need to use the SOP trick!

Optional: Finiding SOP Expressions for Full Adder

- Start with the initial expression from the SOP rule learned in Chapter 6:

- Use the distributive law to further isolate the equation:

- First, use the the rule \(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\) (here’s a challenge - try to create two truth tables for each of the expressions to check if they are equivalent) to simplify the first part of the expression:

- Then, use the rule \(\overline{X \oplus Y} = \bar X \bar Y + XY\) (you can use the truth table trick again to see if both expressions are the same) to simplify the second part of the expression:

- Wait a second! The expression now kind of looks similar to a rule we already used in Step 3 (\(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\)), so now we can simplify the expression to its final form:

Now, let’s look at how to find the equation for the carry over bit:

- Start with the initial expression from the SOP rule learned in Chapter 6:

- Use the distributive law to further isolate the equation:

- Use the rule \(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\) to simplify the first part of the expression:

- Use the rule \(X + \bar X = 1\) to simplify the second part of the expression:

- Use the rule \(X*1\) to further simplify the expression to its final form:

Aside: If you are wondering how I knew some of the boolean identities or expressions to substitute, you can find a list of boolean identities in our appendix. Usually, you won’t have to memorize these, so we aren’t going to concern ourselves with understanding their particularities.

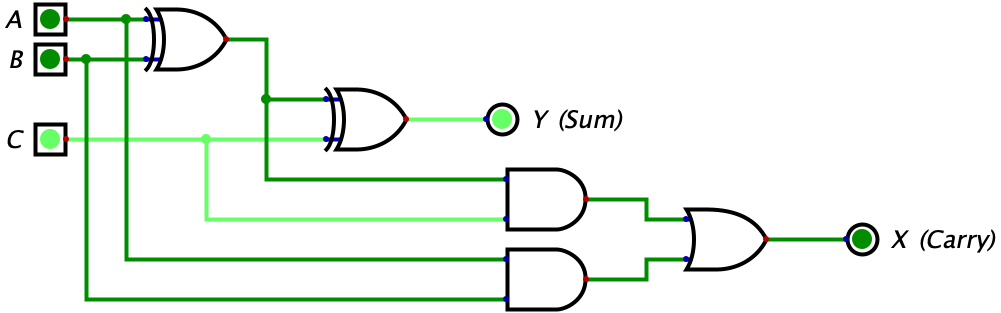

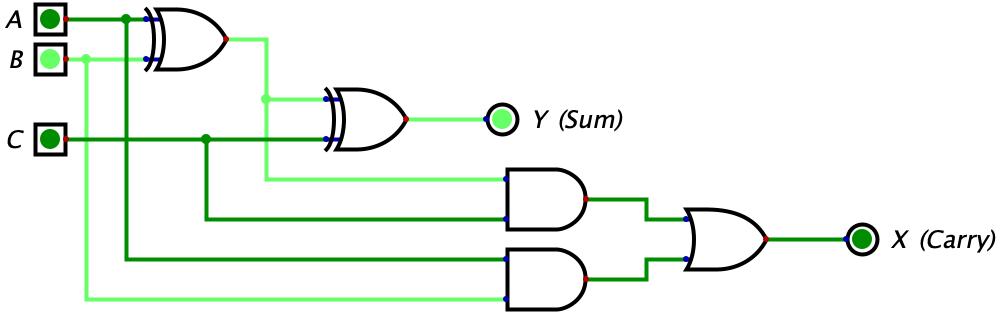

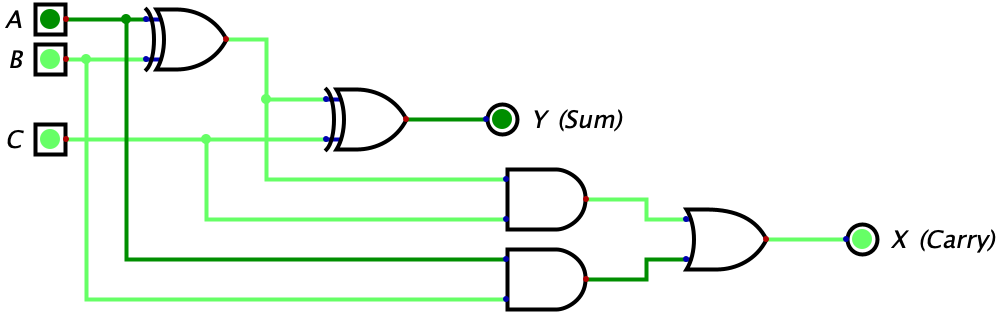

Now we have both of our equations. The equation for the Sum bit is \(A \oplus B \oplus C\) and the equation for the carry over bit is \(C(A \oplus B) + AB\). We can now build our circuit which is below:

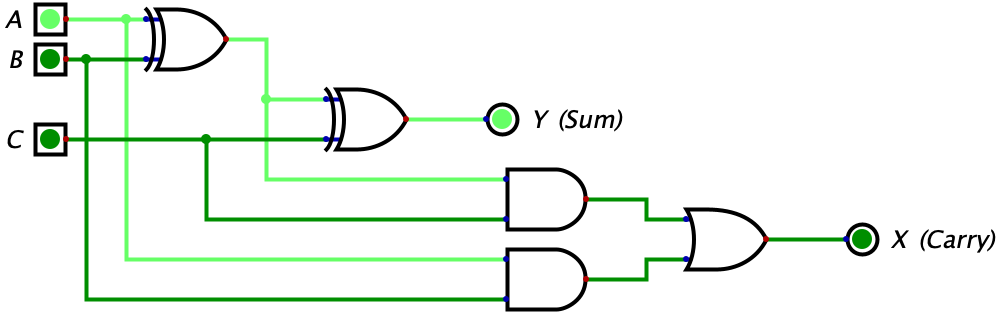

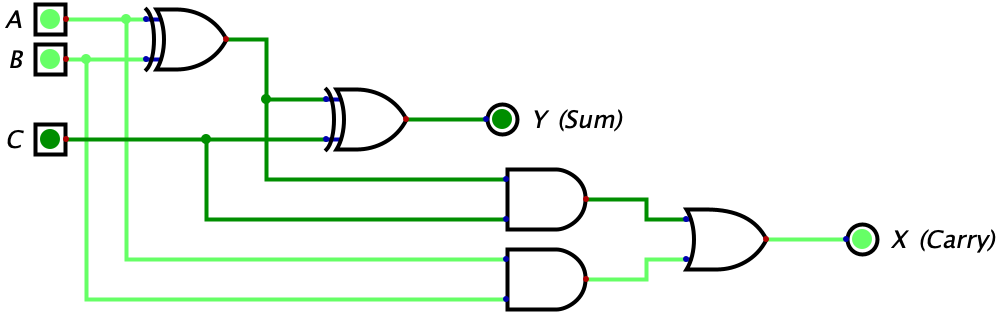

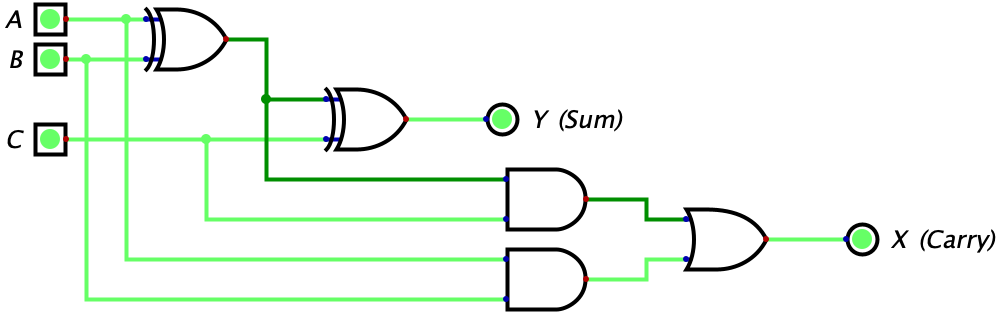

Let’s trace through the inputs in our truth table and look at it’s respective circuit:

| A | B | C | Y (Sum) | X (Carry Out) | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

Cool right? Now, you might be thinking how can we further build on this concept. In Chapter 8, we are going to introduce the idea of ripple Ripple Carry Adders which will allow us to combine multiple Full Adders together to do multi-bit addition and subtraction (and, you’ll see why the carry-out bit was important to learn about)!— title: Chapter 7 date: 2023-11-10 —

< Go BackChapter 07 - Addition with Logic Gates

Topics Covered: Half Adder, Full Adder

At the end of Chapter 6, we learned that a circuit allows us to represent more complex logic beyond the basic AND and OR gates, enabling us to transform our binary inputs into the outputs we desire. An easier way to think about this is by using legos. In the previous chapter, we got introduced to the brick blocks, the tile blocks, the plate blocks, etc. Now, it’s time for us to take those different lego pieces and build our first meaningful circuit. As explained in Chapter 6, logic gates are the building blocks of computers and when you chain logic gates together (to build circuits), you can build an entire computer. With that in mind, we move onto the next step of our journey - building the first component of our computer.

In the earliest chapters we were introduced to base-2 and learned how to add two binary numbers together. In this chapter, let’s automate this process by designing a circuit that takes in two binary numbers as input and outputs the sum of those two numbers. We only saw a few elementary circuits in the previous chapter, so this task may sound daunting at first. But don’t worry! We will build this circuit from the ground up to make it as clear as possible.

I just want to make a quick note by stating that you can build a circuit to do a lot of different things. But, we are going to start out by building circuits that add binary values together for two reasons. First, if you take any computer science degree, most classes are going to start from the ground up just like we did with addition in kindergarden and first grade and work their way up in difficulty. And the second reason is that, in early computing, most computers were built to serve basic needs such as solving arithmetic problems. So, I think it would be helpful to follow this course and then build up our knowledge.

You already know that computers can add incredibly large numbers together, but for the sake of us getting started, we will restrict our circuit to adding two 1-bit values (recall that a bit is a binary digit), namely \(A\) and \(B\). Let’s take an example below as a first contender of a circuit that takes 1-bit values \(A\) and \(B\) as input and outputs their sum (\(A+B\)) as \(X\):

Wait a minute, isn’t this just the OR gate we learned about last chapter? You are indeed correct, but let’s look at it closer and see if it is capable of 1-bit addition. We can check the validity of this circuit by seeing what it outputs for different combinations of input values. If the circuit outputs the correct value for every input combination, we have a valid contender. Otherwise, it means we have an error that we must reconsider. Let’s see how this circuit behaves when both of the inputs are set to 0 (\(X=Y=0\)):

Essentially, this circuit adds two numbers together (in this case, a 0 and a 0) and outputs a number (which again, is 0). This simple, 1-gate circuit outputs the correct value for this specific set of inputs. Congrats, you just build your first circuit! In this example, what we are trying to demonstrate is that the OR gate can be used to add two numbers together and is a simple addition circuit (which was also briefly mentioned in Chapter 6).

Aside: In the example above, the A, B, X which are all 0s are not the number 0, but the bit 0, which is equivalent to the number 0 (i.e. \(0_2=0_{10}\)). So, technically, we are adding the bit 0 (the number 0) to another bit 0 (the number 0) giving us the bit 0 (the number 0). Review Chapter 3 if this does not make sense!

Let’s see how this circuit works for a different set of inputs:

Here, we are adding the bit 0 (number 0) with the bit 1 (number 1) which gives us the bit 1 (number 1). In other terms, this equation can be written as \(0_{2}+1_{2}=1_{2}\). Once again, this circuit outputs the value we would expect given the inputs. Makes sense right? I know I’m definetly boring you, so let’s look a slightly harder example:

Here, we are adding the \(1_2\) (which equals \(1_{10}\)) with \(1_2\) which gives us \(1_2\). If you realized there’s a mistake here, you’re right. \(1_{10}\) plus \(1_{10}\) should be returning the number 2 (written as \(10_2\) in binary - notice how we need two bits to express the result). You might be thinking that there is no possible way we can represent \(10_2\) with just one OR gate since it only outputs one bit. So clearly, our initial guess that an OR gate could be used to add numbers was incorrect. This doesn’t mean that the idea was entirely wrong, but that we will need to expand upon our original circuit to make sure it works correctly for all possible input combinations. This is where things get exciting.

Remember when I was talking about the lego analogy earlier? This is where we use that intuition. Just as we can connect different legos with each other to build more complicated structures, we can connect different logic gates to build more complicated circuits.

Instead of trying a bunch of different circuit combinations until we find one that can successfully add two 1-bit numbers, I will go ahead and give you the correct, complete circuit. From there, we will inspect why it is correct. As it turns out, the correct circuit we have been trying to describe is popular enough to have a name: the half-adder; the half adder is given by the diagram below:

Since this circuit has two outputs, we can represent it’s equation as \(A_{2}+B_{2}=YX_{2}\). In the circuit above, the X acts as the least significant bit (the sum bit) and the Y acts as the most significant bit (the carry-out bit).

Before we look at the internals of the circuit, let’s create a truth table to make sure that it outputs the correct value for any of the possible input combinations. The completed table has been given below, but it would be a good exercise for you to try and fill this out on your own.

| A | B | X (Sum) | Y (Carry Out) | Decimal (Base 10) Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | \(0+0=0\) |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | \(0+1=1\) |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | \(1+0=1\) |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | \(1+1=2\) |

Reading through the rows of the table, you should be able to verify that the circuit is outputting the correct values for each of the input combinations. This is pretty cool work! Just one chapter ago, you were being introduced to logic gates, and now you have created a simple yet powerful circuit that solves a real world need. The true power will come as we build a circuit that can add numbers bigger than one bit; we will shortly be able to build a logic gate addition circuit that can add large numbers faster than any human can. But before we jump ahead, let’s look at at the gates inside the half adder and see why they accomplish the goal of addition.

Let’s start with that XOR gate which is calculating the least significant bit. In our original circuit, we had an OR gate, so how exactly did we end up with an XOR gate? Well, the OR gate was sufficient for three of the four input cases: \(0_2 + 0_2\), \(0_2 + 1_2\), and \(1_2 + 0_2\). The case where the OR gate failed was \(1_2 + 1_2\). In that scenario, we know that the least significant bit of the result should be a zero (i.e. the solution is \(10_2\) and we are looking at the rightmost bit which should be a zero). But our circuit incorrectly outputted a \(1\). So, what we are looking for is a circuit that outputs a \(0\) when both the inputs are \(0\), a \(1\) when either of the inputs are \(1\), but a \(0\) when both of the inputs are \(1\). Does this sound familiar? This is the exact behavior of an XOR gate! So, replacing our OR gate with an XOR gate generates the correct output of the rightmost bit for each of the 4 possible input combinations.

We’ve solved the issue of the rightmost bit, so now we must look at the other challenge of the leftmost bit. We have already seen that the only time that we need the left most bit is if the sum of the two inputs cannot be represented in a single bit. The only input combination that causes this to happen is when we are adding \(1_2\) and \(1_2\). In that scenario, we know the output should be \(10_2\). In the previous paragraph, we saw how replacing the OR gate with an XOR gate makes the circuit correctly output a zero for the right bit. So, how do we make sure that the circuit outputs a one for the left bit? Well the key thing to realize is that we only need to use the left bit when we are trying to represent the number \(2_{10}\). If both of the inputs are \(1\)’s then the left output bit should be \(1\), otherwise it should be a \(0\). Does this sound familiar? It’s just the AND gate you already know about!

Now we can see why the half adder uses a XOR gate and an AND gate instead of using a normal OR gate.

If we combine both of these bits together (in the form of YX with the X bit being the least significant bit and the Y bit being the most significant bit), we can have an output now that correctly represents the equation \(1_{2}+1_{2}=2_{10}\) because the number 2 can be represented as 10 in binary. Here is an example of the circuit below in this scenario:

Here is another example of using a half adder for the equation \(1_{2}+0_{2}=1_{10}\):

In this example, we can see that the output is \(01_2\) (equivalently, \(1_{10}\)). Again, the \(X\) is used as the least significant bit and the \(Y\) is used as the most significant bit.

At this point, you should understand that a half adder is a circuit that takes in two 1-bit values and outputs the sum of those values. At most, we will need two bits to represent the sum of two 1 bit values, so our circuit has two outputs. You should also intuitively understand the construction of this circuit and how the XOR and AND gates are used for the corresponding bit position outputs.

There’s actually another way we can interpret the meaning of a half adder, as follows: a half adder enables us to perform the binary addition of two numbers but only for one digit position in those two numbers. Even after rereading that a handful of times, my message may not be clear. Suppose we are adding the randomly generated numbers \(1011_2\) and \(0010_2\). Since the half adder can add two one-bit numbers, we can use the half adder to add the right most bits of our two input numbers (i.e. \(1_2 + 0_2\)). When we add numbers in both binary and decimal, we work from right to left, adding the digits at each position for each step. The carry out from the half adder is the same carry out we get when we are adding a specific digit position of two binary numbers.

If a half-adder can be used to add one digit position of two binary numbers, does this mean we could use 4 half-adders to compute the sum of the 4-bit numbers in the preceding paragraph? The unfortunate answer is no. Why not? The issue is that, if a certain digit position has a carry out, we know that needs to get considered when we add the next digit to the left. But the input to a half adder is just the two bits being added. Without a way of handling the carry-in, the half adder is not sufficient. What we would like to do, moving forward, is adjust our half adder so that it recieves a third input which is the carry-in. If we are able to make this update, then we will eventually see that we can chain 4 of these adders together to add any two 4 bit numbers. Similarly, we could chain 8 of these adders together to add any two 8 bit numbers. That is exactly what we will do in the following paragraphs. This updated circuit we are trying to build is also popular enough to have a name: the full-adder.

Remember how we were talking about lego bricks earlier? Well, you might hate me, but we are going to add another brick on top of our current circuit. Now, we want to add another input to our circuit and call it the carry-in bit. So now we want to add the A, B, and C (carry-in) bits together to output a sum bit (X) and a carry-out bit (Y), so the equation we are now trying to build our circuit for can be represented by \(A_{2}+B_{2}+C{2}=YX{2}\). Let’s take a look at the truth table and build the full adder circuit (again, this truth table is a representation of adding 3 1-bit values and their ouputs):

| A | B | C | Y (Carry Out) | X (Sum) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Aside: If the above truth table is still confusing, think about it this way. Again, the equation we are trying to represent with the truth table and circuit is \(A_{2}+B_{2}+C_{2}=YX_{2}\). If we add any row of values together, such as the last one where all the inputs are equal to the binary bit 1, then an easy trick we can do to find the output is convert all the inputs to numbers (which in this case are all equal to 1), add them (the result being 3), and then convert them back to binary (which gives us \(11_2\)). All we are really doing is adding three 1-bit values, instead of two.

Next, we are going to use the SOP trick we learned in Chapter 6 to construct and simplify an expression for the truth table above. If you want to skip this part, feel free. I only included this part if you wanted to go over another SOP example (as long as you understand that you can take the ouput of a truth table, convert it to a boolean expression, and then use that expression to build a circuit, you understand the basis of how to build a logical circuit) Let’s create an equation for the Sum bit:

- Start with the initial expression from the SOP rule learned in Chapter 6:

- Use the distributive law to further isolate the equation:

- First, use the the rule \(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\) (here’s a challenge - try to create two truth tables for each of the expressions to check if they are equivalent) to simplify the first part of the expression:

- Then, use the rule \(\overline{X \oplus Y} = \bar X \bar Y + XY\) (you can use the truth table trick again to see if both expressions are the same) to simplify the second part of the expression:

- Wait a second! The expression now kind of looks similar to a rule we already used in Step 3 (\(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\)), so now we can simplify the expression to its final form:

Now, let’s look at how to find the equation for the carry over bit:

- Start with the initial expression from the SOP rule learned in Chapter 6:

- Use the distributive law to further isolate the equation:

- Use the rule \(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\) to simplify the first part of the expression:

- Use the rule \(X + \bar X = 1\) to simplify the second part of the expression:

- Use the rule \(X*1\) to further simplify the expression to its final form:

Aside: If you are wondering how I knew some of the boolean identities or expressions to substitute, you can find a list of boolean identities in our appendix. Usually, you won’t have to memorize these, so we aren’t going to concern ourselves with understanding their particularities.

Now we have both of our equations. The equation for the Sum bit is \(A \oplus B \oplus C\) and the equation for the carry over bit is \(C(A \oplus B) + AB\). We can now build our circuit which is below:

Let’s trace through the inputs in our truth table and look at it’s respective circuit:

| A | B | C | X (Sum) | Y (Carry Out) | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

Cool right? Now, you might be thinking how can we further build on this concept. In Chapter 8, we are going to introduce the idea of ripple Ripple Carry Adders which will allow us to combine multiple Full Adders together to do multi-bit addition and subtraction (and, you’ll see why the carry-out bit was important to learn about)!