Let's Understand How a CPU Works

Designing a CPU from the ground up, with no knowledge needed

Chapter 06 - Logic Gates

Topics Covered: Elementary Logic Gates, Truth Tables, Basic Circuits, The Universal Gate

Now that I’ve made you suffer through enough chapters of binary, it’s time to introduce a seperate yet similarly related concept: logic gates. There’s a few different types of logic gates we will need to understand, so I will introduce them one-by-one and then we will circle back and understand the bigger picture. This chapter should (hopefully) be a lighter read compared from the last few which probably involved you using a calculator to double check everything I was saying.

Simply put, a logic gate takes in a variable number of inputs (atleast 1) and produce a single output. The interesting part, that all the inputs and outputs are either 0’s or 1’s. We have spent a few painful chapters understanding the nuances of binary, but you can put that aside for this chapter. In the next chapter, the connection between this chapter and all the previous ones will become apparent.

AND Gate

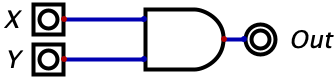

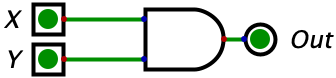

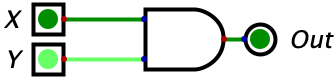

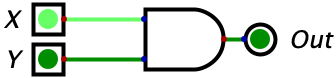

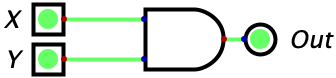

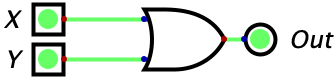

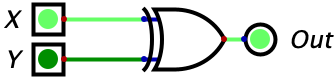

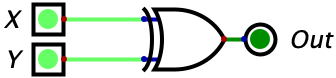

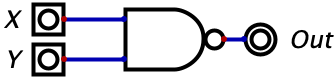

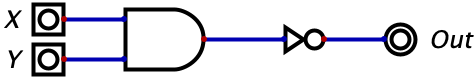

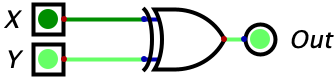

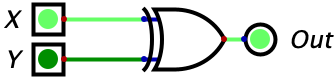

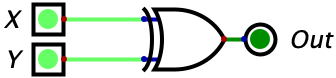

Let’s start with the AND gate which takes in two inputs, and produces one output. If both of the inputs are 1, then the output of the AND gate is 1. For any other combination of inputs, the output will be a zero. The following image is what an AND gate looks like: X and Y serve as the two inputs and the output is given on the right hand side.

Recall that, in the picture above, X and Y are binary inputs. So X can be either 0 or 1 just as Y can be either 0 or 1. We know that the only time that Output=1 is when \(X=1\) and \(Y=1\). Another way to view the functionality of the gate is by giving a truth table. A truth table is a table (duh) that enumerates all of the different possible input combinations on the rows while providing the output of the logic gate on the right-most column. See the table below. There are only four rows in this table, because with two binary inputs, there are only four different input combinations (try invent another one if you don’t believe me).

Remark: For the following diagrams (and all diagrams in subsequent chapters), the darker green is used to represent a 0 while the brighter green represents a 1. The lines on the diagrams are wires, and the only thing you need to recall is that when we put a 0 or a 1 on a wire (i.e. electricity or no electricity), the wire will conduct that value over it’s entire length.

AND Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | AND | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

OR Gate

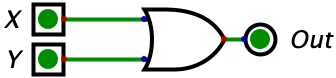

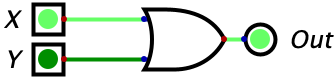

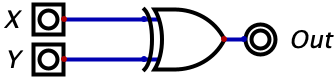

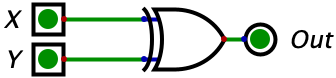

Now, lets move on to the OR gate which also takes in two inputs. The difference here is that this gate will output a 1 whenever atleast 1 of the inputs is 1. If both of the inputs are a one, the output of the gate will still be 1. It also does not matter which of the inputs is 1, the output will be 1 as long as either of the gates is 1. With this information, we can reason that the only time an OR gate will ever output a 0 is if both of the inputs are 0’s. Here’s what an OR gate with inputs named X and Y looks like:

Just as we gave a truth table for the AND gate, below is the truth table for an OR gate.

OR Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | OR | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

XOR Gate

Similar to the OR gate is the XOR gate which means “Exclusive OR”. The difference between this gate and the regular OR gate is that this will only output a 1 if exactly 1 of the inputs is 1. So, if both of the inputs are 1’s, then the gate will output a zero. Besides this, the other three rows in the truth table remain unaffected. A picture of the gate and truth table are given below.

XOR Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | XOR | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

NOT Gate

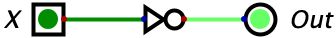

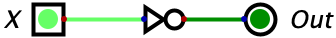

The NOT gate, sometimes called an inverter, is different than the rest we have considered so far because it only takes in one input. Since there is one input and the input is binary, we know that the truth table will only have two rows to represent the two sole possible input values. The inverter will output the inverse of the input. So, 1’s become 0’s and vice versa. Below is an image of an inverter followed by its corresponding truth table.

NOT Gate Truth Table:

| X | NOT | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 |  |

NAND Gate

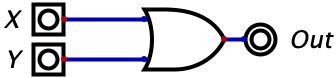

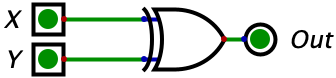

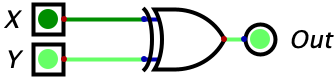

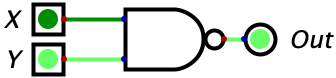

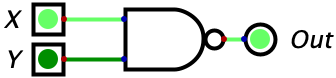

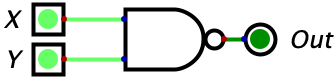

Now we move onto the the NAND gate which, in English, reads “Not AND”. This gate will take whatever the output is of the AND gate and invert it. The NAND gate will output a 1 unless both inputs are 1’s in which case it will output a zero. This means the the truth table will be the exact opposite of the AND gate’s truth table. The diagram and truth table are given below.

NAND Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | NAND | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

What’s interesting is that the NAND gate can be constructed by taking a regular AND gate and then feeding the input through a NOT gate. This is entirely valid, we can chain logic gates together to build more powerful circuits. So, this circuit below is functionally equivalent to a NAND gate.

We have subtly introduced a new concept: logic circuits. When we feed the output of a logic gate into the input of another logic gate, we can create more useful and complex circuits. Whereas a logic gate always takes in one or more input and produces a single output, a logic circuit takes one or more inputs and produces a variable number of outputs. We will see this in action in future chapters.

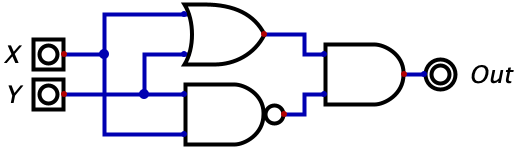

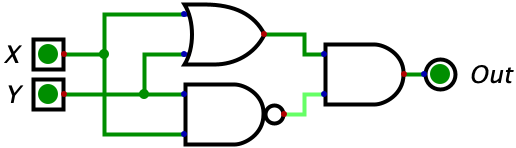

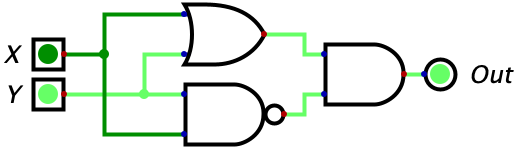

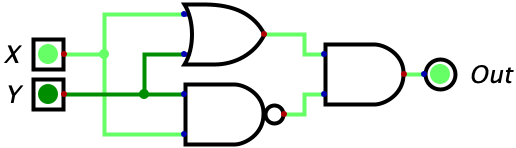

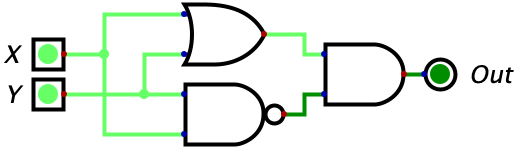

Similarly, we can construct the XOR gate with the following combination of other logic gates.

We can verify this is equivalent by comparing the truth tables.

| X | Y | XOR | Picture | New Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

|

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

|

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

|

| 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

|

This one is a little bit harder to understand. The easiest option is to create a truth table for this circuit and then compare it against the truth table for the XOR gate to see that they always output the same value for any input. If you’re like me, this alone won’t satisfy you since you want an intuitive explanation. Here is how I would reason through this: the circuit ends with an AND gate which means it only outputs a 1 when both of the inputs are 1’s. How do we make the first input a 1? The first input to the AND gate will be a one whenever X or Y is true since the input to the AND gate is the output of an OR gate. How do we make the second input to the AND gate a 1? We make the output of the NAND gate a 1. This happens as long as the inputs are not both 1. So we know the two conditions, and we need them to be true simultaneously. So putting this together, we can reason that the circuit will only output a 1 if “atleast X or Y is a 1 BUT not both of them are 1”. And this is exactly how we described the XOR gate!

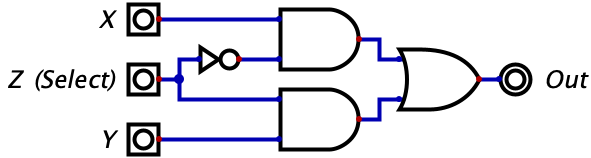

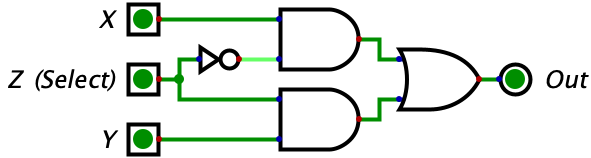

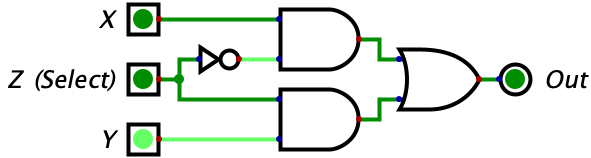

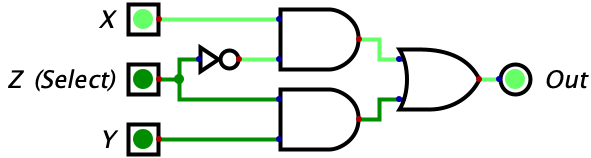

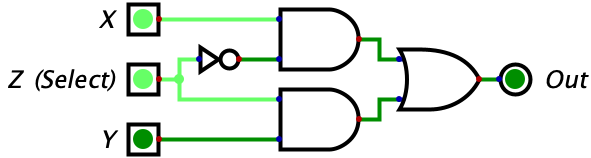

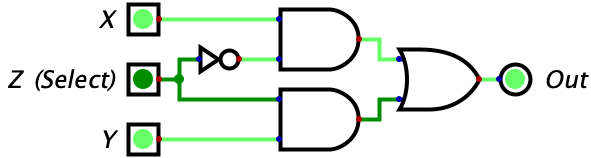

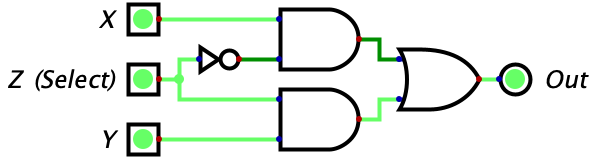

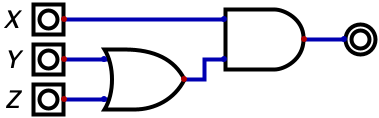

These few logic gates may seem very simple to understand compared to binary, but it turns out they can be chained together to do some pretty interesting things. Consider the circuit below with three inputs which, at first glance, probably looks like gibberish. But if you make a truth table for it, you will see that the circuit is a switch. Whenever Z is 0 the gate outputs whatever the value of X is. Whenever Z is 1, the gate outputs whatever the value of Y is. So, Z is effectively switching the output between X and Y. Pretty neat!

The truth table has been given below, but you should try complete it on your own.

| X | Y | Z | Output | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

Let’s try make some sense of this logic diagram intuitively. We notice that the output of the entire circuit is the two values of the AND gates OR’d together. So, as long as one of the AND gates is outputting a 1, then the entire circuit will output a 1. However, if neither of the gates output a 1, then the entire circuit will output a zero. Then, we look at the two AND gates and make the powerful observation that the input Z is being fed into both of the AND gates (although one is indirect). The value of Z feeds straight into the bottom AND gate while the top AND gate recieves the negated value of Z. This means that whenever Z is equal to 1, a 0 is fed into the top AND gate while a 1 is fed into the bottom AND gate. Conversely, whenever Z is equal to 0, a 1 is fed into the top AND gate while a 0 is fed into the bottom AND gate.

Why does this matter? Well we know that an AND gate will only output a 1 if both of its inputs are 1. Combine this with the fact that, for any value of Z, one of the AND gates will recieve a 1 for one of its inputs while the other will recieve a 0. The AND gate that recieves a zero will automatically output a zero, regardless of it’s other input, since this is a property of the AND gate (i.e. needing both of its inputs to be 1s for output to be 1). So, the value of Z will effectively shut off one AND gate by giving it a 0 for an input.

When Z is 0, the bottom AND gate is ‘shut off’ and outputs a zero. So, the output of the overall circuit is equal to 0 OR’d with the output of the top AND gate. Since the OR gate only turns on when one of the inputs is a 1, and we know one of the inputs is already a 0, we can reason that the output of the entire circuit will equal the output of the upper AND gate. So, what is the output of the upper AND gate? It would be 1 (from Z) OR’d with the value of X. With similar reasoning, we can see that this simply equals the value of X. So, when Z is 0, we allow the value of X to ‘flow’ through the circuit to the output. We also can see how there is no possibility of interference since the entire bottom half of the diagram is guaranteed to be zeroed out in this case.

When Z is 1, the exact reverse thing happens! The top AND gate is forced to output a zero since one of its inputs is a zero. Then, the output of the entire circuit equals the output of the bottom AND gate. The output of the bottom AND gate equals the value of Y since we know the other input is the 1 coming from Z. So, the output of the entire circuit is the value of Z.

For some readers, everything I just said will make sense. For others, however, only half of what I just explained will click. Don’t read ahead until you are able to clearly understand what was just written. This is a new concept, so don’t be discouraged if it doesn’t immediately make sense. On top of it being a new concept, I am also intentionally introducing this to you at a fast pace to avoid getting into the nitty-gritty.

A better way of expressing circuits

So far, I have been using diagrams to visualize circuits, but only using diagrams will become complicated as we move forward in the next chapters. Instead, it would be nice if we could represent some of these diagrams using just text. Fortunately, this problem has already been solved, so we will spend some time here seeing how we can express logic gates in a textual form. For this subsection, lets assume that \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), or any letter is a binary input (i.e. a variable that takes on either the value 1 or the value 0).

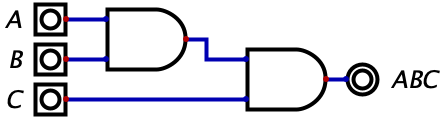

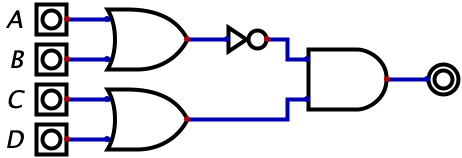

We start with the logical AND expression, which can be represented with multiplication or the absence of a sign. So, \(A*B\) and \(AB\) are equivalent expressions that read in English as “A and B”. With just two inputs, this can easily be translated to a simple logic gate with two inputs. If we gave the expression \(ABC\) (equivalent to \(A*B*C\)), then this translates to “A and B and C”. But the AND gate we learned about only takes two inputs? Well, logical expressions and logic circuits are very similar, but you usually need to find a way to express a logical expression using logic gates. In the case of \(ABC\), we can easily invent the circuit below:

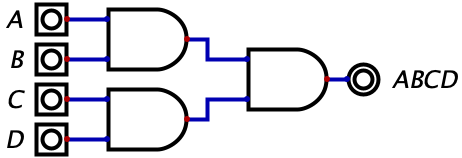

We could even scale this up to any number of variables. Here’s how the expression \(ABCD\) would look like as a circuit:

Before we move on to see how we can textually represent other logic gates, let’s understand why we use multiplication for representing the logical AND. Recall that in an expression, all of the variables (\(X\), \(Y\), \(Z\), etc.) are binary inputs. When we go to evaluate a logical expression, we substitute in 0’s and 1’s accordingly for all of the variables and after some manipulation, expect to end up with either 0 or 1 (because the expression has to evaluate to a single binary value). So, if you recall from your high school algebra class, if we multiply anything by zero, the final output is zero. So when we have an expression such as \(X*Y*Z\), if any variable is zero, then the entire thing resolves to zero, and the only case which this can evaluate to a 1 is if all three variables are one. It’s convenient that our notation for logical expression abides by basic algebraic properties since it eases your intuitive ability to grasp what an expression is saying. The reason we can omit the explicit multiplication signs (\(XYZ\) instead of \(X*Y*Z\)) also relates to algebra. If \(P\) is a variable, then algebra tells us that \(5p\) is equivalent to \(5*p\), so in the latter case, the use of the multiplication sign isn’t required since we can infer that a lack of an operator means to multiply the two operands.

So, we’ve seen how the logical AND can be represented in this written form, so how do logical OR’s work? The answer is with addition. \(X + Y\) reads out to “X or Y”. Similarly, \(X + Y + Z\) reads out to “X or Y or Z”. The (roughly speaking) reason we use the addition sign to represent logical OR is because you need only one of the variables to evaluate to 1 for the expression to be true (i.e. \(0 + 1 = 1\)).

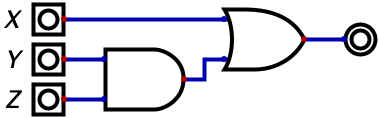

Just as logic gates can be chained together, operators in a logical statement can be chained together. For example \(X + YZ\) would translate to “X or both Y and Z”. With logic gates, this would look like the diagram below.

As is the case with algebra, the use of parenthesis is valid (and often necessary). That PEMDAS acronym you haven’t heard in years is valid here for specifying order of operations in that parenthesis should be evaluated before multiplication which should be evaluated before addition (the rest of the operators in PEMDAS don’t really exist in our means of representing expressions). For sake of illustration, the following expression is visualized by the diagram below: \(X(Y + Z)\)

For logical negation (NOT), there are two different but equally valid representations: \(\neg{X}\) or \(\overline{X}\). You will see these used interchangeably online, but for the sake of this book, we will stick to the latter representation. So the expression \(\overline{(A + B)}(C + D)\) can be represented with logic gates accordingly:

To represent XOR, we have this odd looking symbol: \(\oplus\). So \(X\oplus Y\) is the exclusive-OR between variables X and Y.

As it turns out, those three operators combined with the order of operations you already know intuitively are enough to represent any combination of logic gates. For example, although we don’t have a NAND symbol, we can represent NAND with an inverted AND: \(\overline{XY}\)

As you can probably imagine, these expressions can get incredibly complicated and virtually impossible to read. There is an entire field of study that involves simplying expressions down as much as possible. In many cases, it is easy to take a convoluted expression and simplify it down to a more readable expression. For example, the following expressions are logically equal but the second is more readable than the first: \(AB + DA + AC \equiv A(B + D +C)\) (The triple equals is used to show logical equality). Reducing expressions can get complicated rather quickly, and I don’t want it to be a primary concern of this book. As we introduce and simplify expressions in the future, you will either be presented with the steps taken to simplify the expression or given the final reduced expression. In either scenario, you do not need to focus heavily on how the statements were simplified, and it is safe for you to accept our simplified equations as the truth.

That being said, there are two famous simplifications that I will provide below. These simplifications are called De Morgan’s laws and come up frequently in expression simplification. You should take some time to reason through why the two claims are logically true.

\[\overline{AB} \equiv \overline{A} + \overline{B}\] \[\overline{A + B} \equiv \overline{A}\ *\ \overline{B}\]The Bigger Picture

We have now introduced these very basic structures called logic gates. You immediately saw how they can get complicated when you start chaining them together, but that such combinations actually enable you to build rather interesting circuits. I will now make a claim which, barring one or two minor exceptions which we will later address, is both true and remarkably powerful.

Claim: computer processors are built entirely of logic gates. You might be reading that in denial, but this is the unexaggerated truth: logic gates are the building blocks of computers. By chaining hundreds, millions, or even billions of logic gates together, you can build a fully functional computer. And that is the exact goal of this book.

You saw how we can chain logic gates together to build a switch, so in the coming chapters we will explore more complex yet powerful arrangements of logic gates that implement other useful circuits. We will then combine these known circuits together to build an entire computer.

If logic gates can be used to build computers, and you are holding a physical computer in your hand right now, does that mean logic gates physically exist? The answer is yes, you can seriously purchase a 10 pack of AND gates on Amazon for $6.

Let’s actually take a minor digression to see how the physical chips work. If you click the link, you’ll quickly see that the AND gate on Amazon looks nothing like the AND gates in our logic diagram.

In the diagram, pins 7 and 14 are used to power the chip, so we can ignore those. Look at the first three pins, however, and you will see an AND gate. The first two pins are the input while the third pin is the output. This means that if you connect pins 1 and 2 to wires and then place electricity on the both of the wires (hence the AND), the chip will put electricity onto the third pin. Looking at the rest of the diagram, you can see that there are a total of four AND gates on this chip. You do not need to understand how these chips are physically built, and if I’m being honest, I don’t have the clearest understanding myself. We will build our computer strictly using logic gates, and that will be the lowest level of understanding we have for how this computer can be physically built. If you really, really want to know how logic gates are physically built, there is an abundance of resources online, none of which make perfect sense to me. So yes, perhaps I lied a little bit in the introduction when I claimed that you would understand how a computer works from scratch. In reality, you will understand how computers work down to logic gates, and we will leave that very lowest level of physically building the gates aside. For those of you curious, there is actually a really neat article about someone who implemented logic gates with water. If you’re looking for a little more explanation on how logic gates work but don’t want to go into the nitty-gritty of electricity, then this article should hopefully satisfy your craving.

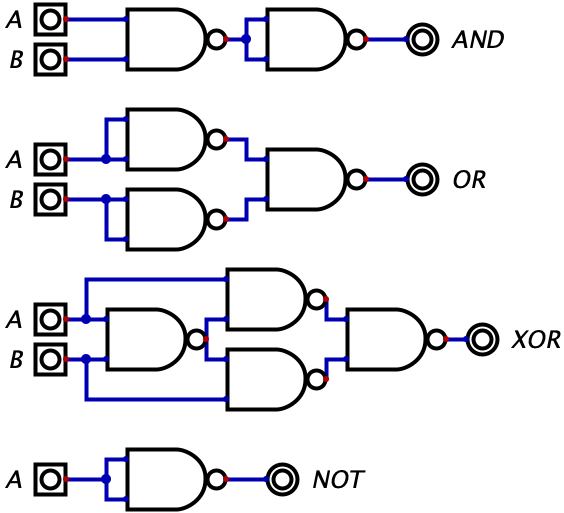

The Universal Gate (Optional)

This chapter has already covered enough material, and I don’t want to distract you by adding even more to that load. But, there is one concept that I remember blowing my mind when I was first learning about logic gates.

The mindblowing fact: All logic gates can be constructed by using NAND gates. If you don’t believe me, then take a look at the diagram below which shows some of the gate construction and verify that the truth tables work out equivalently.

We previously claimed that you can build an entire computer out of logic gates. Now that we know the NAND gate can be used to construct any other logic gate, we can make the secondary claim that you can build an entire computer solely using NAND gates. This is pretty neat!