Let's Understand How a CPU Works

Designing a CPU from the ground up, with no knowledge needed

Chapter 02 - How Humans Intuitively Represent Numbers

Topics Covered: Formalizing Decimal, Base-10 Meaning

You’ve likely heard of the notion that computers only understand 0’s and 1’s, so in this section will make sense of that.

Let’s start with the number 845 which was randomly chosen for the sake of formalizing the way your mind intuitively perceives multi-digit numbers. 845, along with any other number, can be expressed in a less comapct way as a sum of it’s digit positions. Instead of trying to confuse you by explaining, lets work this through by example. It should be no surprise that \(845 = 800 + 40 + 5\). Similarly, the number 94 can be expressed as the sum of 90 and 4. The same decomposition can be used on even larger numbers: \(29742 = 20000 + 9000+ 700 + 40 + 2\). No matter how large the example gets, your mind is able to easily verify all these statements as true by adding up all of the numbers that form their components.

Aside: For the next part, you will need to remember the mathematical rule that any digit raised to the power of 0 is equal to 1. That is \(1^0=2^0=3^0=...=1\)

Now let’s try express the same number in a different way: \(845=8*10^2+4*10^1+5*10^0\) At a first glance, this may not have seem true, but with a little bit of thinking, you should be able to verify that the left hand and ride hand side of that expression are equivalent. Although it seems like you’ve never thought of a number this way, this is the exact way your intuition processes these larger numbers. You’ve probably heard of the ‘ones place’, ‘tens place’, ‘hundreds place’, ‘thousands place’, and so on. Yet, you’ve never seen a number be described as this visually unappealing sum of exponents being multiplied by weights. The truth is, however, that these two concepts are the exact same. The right-most digit in a number is the ones place, and notice how \(10^0=1\). Similarly, the digit second from the right is known as the tens place, and notice how \(10^1 = 10\). The same logic holds for the next digit place which is known as the hundreds place, and once again notice how \(10^2=100\). So really, the long expression at the start of the paragraph can be simplified to \(845=8*100 + 4*10 + 5*1 = 800 + 40 + 5\). And now we’re back at the original expression which was far from confusing in the previous paragraph.

\[8*10^2 + 4*10^1 + 5*10^0\] \[8*100 + 4*10 + 5*1\] \[800 + 40 + 5\] \[845\]In this manner, you can express any number as a weighted sum of digits and corresponding powers of ten. Before we move on and explain why we are bothering with all of this, there are two more observations worth highlighting.

First, notice in any digit position, there can be one of ten distinct values: 0, 1, 2, 3, … , 9 (Yes, 10 not 9 since 0 is a valid digit). This is our intuitive way of representing numbers and is formally called ‘Base 10’ or also ‘Decimal’. Shortly, we will introduce a new base (don’t get confused by this yet). To prevent future confusion, when we are referring to base 10 numbers (i.e. the regular way that you and I both represent numbers), I will subscript them with a 10, like so: \(845_{10}\) Don’t let this notation confuse you, just remember when you see that subscript, it means to treat the number the ordinary way you percieve it.

The second observation is a bit more obvious, but will shortly help you understand how counting works in other bases. The observation is that when we are counting in Base 10, if we get to the point where there is a 9 in any digit spot and we want to add one more, we get stuck because 9 is the largest value that can be stored in that position. When we run into that position, we have to ‘carry-over’. More formally, that means to roll the current digit position to a 0 and then add one to the ‘left’ digit. So when we are counting and reach the digit 9, then the next step is to roll the 9 to a 0 and then add one to the next digit position which gives us 10. And if youre wondering what the other digit position is since 9 is a single-digit number, remember that adding 0’s to the front of a value doesn’t change it’s meaning. That is \(9=09=009\). So, in our counting example, you can say that \(09\) is where we begin and then to add 1, we know to roll the 9 back to a 0 and then add one to the next digit position: which is 0 so it just becomes 1. Some more examples would include \(29\) becoming \(30\) or \(149\) becoming \(150\).

Our two step process for handling carry over is to

- Rollback the 9 to a 0

- Add one to the next most significant digit position (i.e. the digit position to the left)

It’s worth noting that the second step can actually trigger any carryover. For example, try to add \(1\) to \(299\). You obviously know that the answer is \(300\), but observe how there are two carry over’s.

I know everything so far has been painfully obvious, but as we finally move forward, formalizing your intuition will prove helpful.

As a recap, let the following table explain the decomposition of the digits of the number \(8459_{10}\)

| 8 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight of Position Expressed as a Power of Ten | \(10^3\) | \(10^2\) | \(10^1\) | \(10^0\) |

| Weight of Position Expressed as a number | 1000 | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Your intuitive name for the digit position | Thousands Place | Hundreds Place | Tens Place | Ones Place |

Chapter 03 - The Language of Computers. Meet Binary

Topics Covered: Base-2 Introduction, Binary Addition, Counting in Binary

Why Computers Cannot Understand Decimal

We are now ready to move on and understand how computers represent numbers. Everything so far has formalized the concept of Base 10, but for reasons that will eventually become apparent, computers cannot (easily) be built in the physical world to represent numbers the same way we do. Why not? Before I briefly explain, I would like to specify that I am no electrical engineer and any rational electrical engineer will probably label this justification as critically flawed. But, we are already operating at a low enough level, and if we went any deeper, then we would be dealing less with computer science and more with physics. Long story short, at some point, engineers have to actually build the computers they design. One ingenous idea is that we can detect the prescense or absence of electricity relatively easy (suppose we are talking about electricity on a wire). With that in mind, engineers decided to let the absence of electricty be interpreted as a 0 and the presence of electricity be represented as a 1. With these two numbers, computers have enough resources to count in ‘Base 2’ which is synonymous with ‘Binary’.

You might be thinking, if engineers could detect the absence and presence of electricity on a wire, why could they also not detect the amount of electricity present. They could then say that no electricity at all is 0, a little bit of electricity can be interpreted as 1, a little more can be interpreted as 2, and so on, with the most amount of electricity being represented as a 9. This would effectively enable computers to count in decimal. However, it turns out that in the physical world, it is really difficult to maintain an exact ‘amount’ of electricity on a wire. The ‘amount’ of electricity on a wire can waver significantly which makes this process useless. If anything in this paragraph was slightly confusing, you don’t need to worry about it. That topic transcends the scope of information I wanted to cover in this series but thought it would be worth discussing to motivate the ‘Why’ aspect of only having 0s and 1s.

Binary/Base-2

So, if you take my word that we can use the presence of electricity to represent 0’s and 1’s when we are talking about electricity on a wire, then we are good to move forward. A first question: If we only have the digits 0 and 1 available, why are you calling this Base 2? Well, in base-10 (i.e. the human language), we only have the digits 0 through 9 available but we call it base-10 not Base-9. The idea being that base-K means you can have K different values in any digit position. Or equivalently stated: A digit in ‘Base K’ can take on values from 0 up to K-1. So, with just 0’s and 1’s, there are only two different values that can occupy any digit position, so we call this Base-2.

So what do numbers look like in base 2? To give you a complete answer, I will pose and then answer the following four questions. After reading and understanding the answers to each of these questions, you will know all you need to understand the black-box that is currently Binary.

- How do you convert numbers from Base-2 to Base-10

- How do you convert numbers from Base-10 to Base-2

- How do you add two Base-2 numbers

- What does counting look like in Base-2

Converting Numbers from Base-2 to Base-10

Any combination of 0’s and 1’s is a valid number in base 2 (Similarly, any combination of the digits 0-9 is a valid number in base 10). Lets consider the binary number \(1101_{2}\). Earlier, I mentioned that I would subscript all numbers in base-10 with a 10, so I will also subscript any base-2 numbers with a 2. Let me answer the question by giving a long form representation of \(1101_{2}\).

\[1101_{2} = 1*2^3 + 1*2^2 + 0*2^1 + 1*2^0\]Hopefully, this reminds you of the long-form expression from the start of this chapter when we decomposed \(845_{10}\). Let me copy that below.

\[845_{10}=8*10^2+4*10^1+5*10^0\]If you read over both of these expressions and recall the painfully obvious facts that I laid out earlier, you can see that the only difference between base-2 and base-10 is the value of the base in the exponentiated terms of the sum (does that explain where the word ‘base’ comes from!). In decimal, each of the digit places was representing a different power of 10: the ones places, tens place, hundreds place, thousands place, etc. In binary, each of the digit places is representing a different power of 2: one (\(2^0\)), two (\(2^1\)), four (\(2^2\)), eight (\(2^3\)), sixteen (\(2^4\)), thirty-two (\(2^5\)), etc.

So, lets take \(1101_{2}\) and start with the right-most digit. The first power of 2 is 0 and \(2^0=1\), so we multiple the value of that digit position, 1, by this power of 2: \(1*1=1\). We will now do the same thing for each of the digit positions, sum up their results, and the final sum will be the decimal (i.e. the recognizable) interpretation of that number.

Let’s move to the next digit position (the second-from-the-right): the value in this spot is 0 and the next power of 2 is \(2^1=2\). The product of these two values is \(0*2=0\).

Then we move onto the next digit position: the value in this spot is 1 and the next power of 2 is \(2^2=4\). The product of these two values if \(1*4=4\).

Then we move onto the last digit position: the value in this spot is 1 and the next power of 2 is \(2^3=8\). The product of these two values is \(1*8=8\).

Lastly, we add together each of the values we computed for each of the digit positions which, in the order from right to left, is: \(1 + 0 + 4 + 8 = 13\). And we did it! The binary number \(1101_{2}\) which originally had no easily interpretable value, has now been deciphered as the decimal number 13. So we have that \(1101_{2}=13_{10}\).

It doesn’t get more complicated than that! Let’s spell this out in steps:

- Start at the right-most digit position

- Let sum = 0 and base = 0

- Multiple the current digit position by \(2^{base}\)

- Add the result of Step 3 to sum

- If there is another digit to process, base = base + 1 and then go back to step 3 considering the next digit position to the left.

Let’s use these steps to work through one more example. Convert the value \(1010101_{2}\) to Base-10. Try work this out for yourself. I will give the expanded out version instead of showing all the steps, but you should get the same result by following the steps above.

\[1010101_{2} = 1*2^6 + 0*2^5 + 1*2^4 + 0*2^3 + 1*2^2 + 0*2^1 + 1*2^0\]When you simplify the right hand side of the expression (all of the values on the right side are in decimal), you will find that \(1010101_{2}=85_{10}\)

Here’s the familiar table from the previous section, but with the current example and specified in base-2

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight of Position Expressed as a Power of Two | \(2^6\) | \(2^5\) | \(2^4\) | \(2^3\) | \(2^2\) | \(2^1\) | \(2^0\) |

| Weight of Position Expressed as a number | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

And with that, you now know to follow the basic steps above to convert numbers from the mysterious base-2 to the easily understandable base-10. This is not something to take lightly, it’s remarkable that a random string of 0’s and 1’s makes no sense to us until we are able to convert it to decimal, and then we understand all there is about that number. For example, we immediately know that \(\$10_{10}\) is a low amount of dollars to pay for a new shirt, but we cannot say the same about \(\$10110_{2}\) with the same congitive ease. In the second scenario, you have to convert the binary number to base 10 to make any sense of it. However, as we will learn in the process of building a computer, CPU’s have no understanding of numerical representation besides base-2. Whenever we are using a computer to perform arithmetic, we type in the input in base 10, but the values are immediately converted to base 2, the operations happen in base 2, and then the very last step is to return the result in base 10 so that us humans can understand it. But the average person has no idea all of that is happening under the hood, but now you do.

One remark: In formalizing base-10, we multiplied each digit position’s weight (some power of 10) by the value of the digit in the corresponding position. In binary, the value of a digit in any position is either 0 or 1. So, if we have a 1 in a position, we simply add the corresponding power of 2 to our running total (since multiplying the weight by 1 is just the weight itself). Similarly, if we have a 0 in a position, we can simply ignore that position and move onto the next since there is no need to multiply by the corresponding position weight since any number multiplied by 0 is 0.

Converting Numbers from Base-10 to Base-2

Converting a base 10 number to a base 2 number is a bit more difficult of a task for it doesn’t always feel intuitive, but the process can be reduced down to an easy set of steps. This sub-section may feel difficult to understand, and that is normal and will take lots of practice to fully grasp. The good part is that you can feel free to skip this subsection if you would like, since in the future chapters of this book, I will do the conversion for you. For those who remain curious, I will explain the conversion process in a more mathy manner.

The question I will answer in this section: what is \(145_{10}\) in binary? To answer this question, I will lay out the steps for the conversion algorithm and then we will use the algorithm to convert \(145_{10}\)

To convert the value \(X_{10}\) to binary

- Start with an empty string which will be the answer = ‘’

- Divide X by 2

- If the remainder of step 2 is 1, prepend a 1 to answer

- If the remainder of step 2 is 0, prepend a 0 to answer (Note that the remainder can only be 0 or 1 since we are dividing by 2)

- X = X/2 (Rounding down in the case of a remainder)

- If X is not zero then go to step 2

You do not need to understand why this algorithm works since it requires a strong intution of binary that you probably won’t have if this is your first time being introduced to the concept.

Let’s work through the example following the steps

- answer = ‘’

- 145/2 = 72.5

- answer = ‘1’

- X = 72

- 72/2 = 36

- answer = ‘01’

- X = 36

- X/2 = 18

- answer = ‘001’

- X = 18

- X/2 = 9

- answer = ‘0001’

- X = 9

- X/2 = 4.5

- answer = ‘10001’

- X = 4

- X/2 = 2

- answer = ‘010001’

- X = 2

- X/2 = 1

- answer = ‘0010001’

- X = 1

- X/2 = 0.5

- answer = ‘10010001’

- X=0

- Stop

Therefore, we have \(145_{10}=10010001_2\). You can verify this by using what you learned in the previous seciton to convert the binary number back to decimal and you should get \(145_{10}\)

How do you add two Base-2 numbers

Let’s recall how we would add two numbers in decimal, say \(780\) and \(956\). We start with the right-most digit position, and add the two numbers. If the result is less than 10 (base-10 sounding familiar?), then we simply put the sum as the first digit in the resulting sum. If the sum does exceed ten, then we put the sum’s remainder when you subtract 10 as the first digit of the resulting sum. Since we carry over, then in the next digit position, we add 1 to the sum of the next two values. We then repeat these steps over and over until we have added all the digits in the corresponding positions. If one value has more digits then the other, we can zero pad the shorter of the two values (i.e. \(567+4=567+004\)). Lastly, if we get to the end, and the final sum carry’s over, then we add a new left-most digit position to our result and give it the value of 1.

In our example, \(0+6=6\) and since \(6<10\), we mark the first digit of our result (i.e the right-most digit also known as the least significant digit) as 6. Then, we consider the next digit position and add \(5+8=13\). Since \(13>10\), we let the position of the result by \(13-10=3\) and then note the carry over. When we look at the next digit position, we add \(7+9+1=17\) (the 1 appears from the carry over of the previous digit position). Since \(17>10\) we let the corresponding digit position of our result by \(17-10=7\). Now, although there are no more digit positions left to sum, our final (most significant) digit position, had a carry over, so we must account for that. You can think of this as one final sum, where the two values are 0, as shown in the table below. In that case we add \(0+0+1=1\) which means we have a \(1\) in the left-most digit position of our result. It is safe to prepend these ‘fake’ zeroes to our numbers under addition because adding zeroes to the front of a number does not change its intrinsic value.

| Computing X+Y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | 0 | 7 | 8 | 0 |

| Y | 0 | 9 | 5 | 6 |

| Sum | 1 | 16+1=17 | 13 | 6 |

| Carry | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Result | 1 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

The concept of carry-over should sound familiar from elementary school, but it is also valuable to understand why we carry over in the first place and why we choose the value 1. This will be explained in the next sub-section. Revisit this after reading that section and this should make sense.

If this all makes sense, then adding numbers in binary should be easy since it follows the same exact process. The only difference, is that in base-2 we carry over when the sum in a digit position is greater than or equal to 2. Similarly, you know that in base-10 we carry over when the sum in a digit position is greater than or equal to 10.

In general:

- You carry over in base-k when the sum in a digit position is greater than or equal to k.

- In that case, the digit you leave in the current position is the remainder of the sum when divided by k.

Let’s try add the following binary numbers \(101_2\) and \(1_2\). The first thing I will do, as seen in the table below, is to zero pad the shorter number so the two digits are the same length. This doesn’t change the value, but makes ‘stacking’ the numbers more visually intuitive for the sake of me explaining. Now we are computing \(101_2 + 001_2\). Just like decimal, we start with the least significant digit position and then work towards the most significant digit position (i.e. right to left). \(1_2+1_2=2_{10}\). This is a carry-over because we only have 0’s and 1’s in binary, so we can’t find a 2 into any digit position (this is formally explained by the two rules listed above). So, we leave a 0 in this digit position of the sum (Rule 2) and mark our carry as 1. Then, we look at the next digit position and add \(0_2+0_2+1_2=1_{10}=1_{2}\). So, the next digit position of our result is 1 since there is no carry. Then the next position we add \(1_2+0_2=1_2=1_{10}\) and there is once again no carry, so the corresponding digit in the result is 1. This gives us the answer \(110_2\)!

I will paste the same exact table as from above but for this example, with the difference being that this is binary arithmetic instead of decimal arithmetic. You can verify by converting the two values to decimal and then asserting that the sum of their decimal values is the same value you get when you convert their binary sum, \(110_2\), to decimal.

| Computing X+Y | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| X | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Y | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sum | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Carry | No | No | Yes |

| Result | 1 | 1 | 0 |

For any digit position, we are adding a combination of 0’s and 1’s (ignoring the carry which you do have to consider). We can specify the outcomes in a table as given below.

| A+B | Sum | Carry Out |

|---|---|---|

| 0+0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0+1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1+0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1+1 | 0 | 1 |

If we wanted to extend this table to include the carry component, we can.

| A+B+Carry In | Sum | Carry Out |

|---|---|---|

| 0+0+0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0+0+1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0+1+0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0+1+1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1+0+0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1+0+1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1+1+0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1+1+1 | 1 | 1 |

Verify that each entry in this table makes sense, and you have a complete understanding of adding binary numbers.

The equivalent table could be specified for decimal numbers, but would have too many entries to show here. For sake of illustration, I will include such a table, but with only a few entries to highlight key ideas

| A+B+Carry In | Sum | Carry Out |

|---|---|---|

| 1+2+1 | 3 | 0 |

| 9+1+0 | 0 | 1 |

| 9+9+0 | 8 | 1 |

| 9+9+1 | 9 | 1 |

Notice how in both decimal and binary, the value of the carry can never be more than one (it is either always zero or one). If this result doesn’t make sense, try find two decimal digits whose sum would have a carry greater than one, and when you are unable to do so, it should become evident. It turns out this property holds for any base.

What does counting look like in Base-2

In both base-2 and base-10, we can think of counting as starting with the number 0, and continuining to add 1 to the result of the last sum.

Given that you know how to add numbers in binary, this section won’t be too long since you already know how to add 1 to any value. But, there are a few worthwile takeaways. When we count in decimal, we take the number we currently have and keep attempting to increment (add one) to the least significant digit position. In some cases this will work: \(8\rightarrow9, 95\rightarrow96,245\rightarrow246\). However, in some instances, this won’t work. For example in \(49\), we can’t simply increment the 9 to a 10 since 10 requires two digit positions and we only have 1 to work with. So, we roll over the 9 to a 0 and add a 1 to the next digit position. That is we roll the 9 in 49 to yield 40 and then try increment the next digit position from a 4 to a 5 which yields us the result of 50. Let’s briefly think about why we carry over one. This might be obvious to some and less clear to others. If we have a 9 in the current digit position and we want to get to the next number, we have an issue with adding 1 to the number. However, we can accomplish the same result by simultaneously adding ten to the number and subtracting 9. Formally put, for some \(X\), \(X+1=X+10-9\). And that is exactly what we are doing when we count, when we roll the 9 to a 0, we are subtracting 9 from \(X\), and when we are adding a 1 to the next digit position, that is synonymous with adding 10 to X.

And this works for any digit position. For example, if we are counting and are currently at 499, we know that we roll the first 9 to a 0 and add a one to the next digit position. Since the second digit position is also a 9, this will result in another carry over and in this case, rolling the 9 to a 0 and adding a 1 to the next most significant digit position can be verified by the fact that \(X+1 = X-99+100 = X-9*10^1 + 1*10^2\). This should hopefully explain where the 9 and 1 come from in our process.

Now in binary, the same process happens, but we rollover whenever we get to a point where a digit position would have a two in it if we were to increment it. So \(0_2\rightarrow1_2\). Then adding a 1 to this would carry so we get, \((01_2=1_2)\rightarrow 10_2\). The carrying over can happen multiple times: \(011_2\rightarrow100_2\). Similarly, \(1111_2\rightarrow10000_2\).

Digression

There is one final remark that I will make related to counting. Just as everything so far in this chapter is seemingly random, the next idea will also appear to be purposeless until many chapters down the road.

Let’s jump back to the familiar base-10 and suppose we are interested in knowing how many different values we can store in a fixed number of digit positions. Suppose you are asked how many different numbers you can represent with a single digit. You intuitively know the answer already, but we can formally solve this by enumerating all of the 1 digit numbers and then seeing how many we have: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. This is ten different numbers (don’t fall into the trap of believing the answer to be 9 because there are actually 10 digits in the range [0, 9]). Easy enough, but now suppose I ask you how many numbers you can represent with two digits. You know the smallest two digit number is 0 and the largest two digit number is 99, so you can easily answer with 100 because you know that there are 100 numbers in the range of [0, 99] (once again don’t fall into the trap of thinking 99 is the answer. There are 99 numbers in the range [1,99] but 100 numbers in the range [0,99]). It turns out, in base 10, this question is easy to answer for any number digit positions. All you need to do is count the number of digits between 0 and the largest value you can represent with the given number of digits.

The method we described is entirely correct, but is a less formal way of getting to the correct answer. Let’s revisit the same question: how many numbers can you represent with two digits. The more mathematical way to answer this question is as follows. In the right-most digit position, there are ten values we can pick from: [0,9]. If we fix that digit position to some value along the range [0,9], then there are ten values we can pick for the other digit position, namely [0, 9]. In summary, if we fix one of the digit positions to a particular value, then we have ten different options for the other digit position. But for the first digit position, we can fix it to one of ten different values. So, if we can pick 1 of 10 values for the first position AND we know that for each selection, we can generate 10 different values for the second digit, then we can multiply these two numbers together to get our final answer \(10*10=100\). In short, there are 10 options for the first slot, and for each of these 10 options, we can generate 10 unique numbers (based on what we put in the remaining digit slot), so it makes sense to multiply these two numbers to count the total number of possible values.

If we know there are 100 values we can represent with two digit positions, and we want to know how many values we can represent with 3 digit positions, we can use the same concept combined with our previous result. For each of the 100 values we can represent with two digits, there are 10 different values we can pick for the third digit that would each generate a new number. For example, for the two digit number \(45\), we can generate each of the following unique three digit numbers: \(045\), \(145\), \(245\), \(345\), \(445\), \(545\), \(645\), \(745\), \(845\), \(945\). So, the same logic tells us that we should multiply our 100 known two-digit values by the 10 different options each number could select for the third new digit to get \(100*10=1000\).

Our Results:

- In base 10, with 1 digit we can represent \(10\) different values

- In base 10, with 2 digits we can represent \(10*10=10^2=100\) different values

- In base 10, with 3 digits we can represent \(10*10*10=10^3=1000\) different values

In general: In base 10, with K digits we can represent \(10*10*...*10=10^k\) different values

We can then perform a similar analysis on base two. With 1 digit, our options are 0 or 1, so there are 2 different values we can represent with two digits. With two digits, we can enumerate the different values as \(00\), \(01\), \(10\), \(11\) which yields four different values. With three digits, we use the fact that there are 4 different values we can represent with two digits. For each of these values, we can obtain a three digit number by adding in a 0 or 1 for the new digit posiiton. This means there are \(2*4=8\) values we can represent with three digits.

Our Results:

- In base 2, with 1 digit we can represent \(2\) different values

- In base 2, with 2 digits we can represent \(2*2=2^2=4\) different values

- In base 2, with 3 digits we can represent \(2*2*2=2^3=8\) different values

In general: In base 2, with K digits we can represent \(2*2*...*2=2^k\) different values

This result will prove to be very useful down the road when we design our computer, but for the immediate time being, we will not use this takeaway.

At this point, you understand everything you need to know about binary to move on to designing the computer.

Chapter 04 - Fixed-Width Numbers

Topics Covered: Bits, Bytes, Width Requirements

In regular decimal, we never think of the number of digit positions we are using. If you want to convey a number to someone else, you just say the number as it is regardless of how many digits it has. Obviously, humans work with numbers that usually use fewer than ~10-15 digits, but we could theoretically convey a number with 100 different digits and it wouldn’t cause an issue. Computers, on the other hand, are not so flexible. As will become evident throughout the next chapters, things have to be both consistent and precise. The computer we design will not be a fan of binary numbers with variable number of digits. Let’s motivate this better with an example.

Suppose somebody hands you a piece of paper and tells you that it’s contents are in binary and that there are 100 numbers written on the sheet. You unfold the paper and see an entire page of 0’s and 1’s. It’s important to remember that the paper’s contents are strictly binary, so there’s no concept of writing each number down on a different line - all we can do is write 0’s and 1’s next to each other. Now you are tasked with converting the 100 numbers back to decimal. Suppose the first ten digits on the paper are \(1001101011\). Do you see the issue yet? How do you know if those ten digits are 10 different 1-bit numbers? Or if the first 5 digits correspond to the first number and the second five corresponding to the next number? Or are there three numbers in those ten bits? It is impossible to know! The issue is that you don’t know how many binary digits (bits) each number will use. Without further specification or more information, this problem is actually impossible to solve. And it turns out, this is a valid issue computers run into. Many chapters down the line, we will discuss the concept of memory which as you probably know is a way to store information. However, all of the information in your computer’s memory is stored as bits, so your computer has some internal rules to be able to distinguish the first value in memory from the second.

An easy solution to this issue, is to set a rule for our computer, that every number will be represented with the same number of bytes. The first rule that we will set for our computer is as follows: all numbers will be represented with eight binary digits. Why 8? The truth is we could pick any number we want to. Eight is a small enough number such that we aren’t working with incredibly large binary digit strings, but also big enough where we aren’t overly restricted. In fact, after we finish designing our computer to represent all numbers with eight binary digits, we will devote a chapter to redesigning the computer to represent all numbers with a different length! In the real world, different computers will use different number of bits. 32 and 64 are both common in modern processors. For those of you who have used a Windows computer and attempted to download something, you probably came across 32-bit and 64-bit versions on the download page - these are different versions of the same product but intended to work on two different types of CPUs!

A brief interjection of computer vocabulary that I will use onwards:

- A bit is a single digit in binary which is either 0 or 1.

- The unique bits: 0, 1

- A nibble is four bits.

- The unique nibbles: \(0000\), \(0001\), \(0010\), \(0011\), \(0100\), \(0101\), \(0110\), \(0111\), \(1000\), \(1001\), \(1010\), \(1011\), \(1100\), \(1101\), \(1110\), \(1111\)

- A byte is eight bits.

- The unique bytes: \(00000000\), \(00000001\), \(00000010\), \(\dots\), \(11111111\)

Aside: In most modern computers, a byte is the smallest unit of memory. We said computers represent all data as 0’s and 1’s, and so the grouping of 8-bits that composes a single byte can be thought of as a unit of information. You’ve probably heard of a megabyte (MB) which is equal to 1 million bytes. On the same line, a gigabyte (GB) is equal to roughly 1 billion bytes. Now you can assign some meaning to these random storage sizes you’ve periodically encountered.

We just set an important rule that will hold for all of the remaining chapters, so let’s look at some of the important consequences.

First, the smallest decimal number we can represent with 8-bits (a byte) is \(0_{10}\) which in binary is now \(0000 0000_2\). Second, the largest binary value we can represent with a byte is \(1111 1111_2\), and if we convert that to decimal we get \(255_{10}\) (do the conversion yourself and verify this. It should also be clear why the string of all 1’s is the biggest number). The second takeaway is important here, if we want to represent the number \(256_{10}\) with our computer, we simply cannot. We can represent \(255_{10}\) and we can represent \(10_{10}\), but if we try to add them, our computer will be unable to represent the value of the sum which is \(265_{10}\). If you don’t believe me, convert \(265_{10}\) to binary and you’ll see that it needs more than 8 bits to be represented.

This is analagous to setting an arbitrary rule that we can’t use more than five digits in decimal. In that world \(99999\) is biggest number, and \(0\) is the smallest number. If you add \(90000\) and \(10000\), although both of those numbers can be represented, then sum \(100000\) cannot be because it uses more than 5 digit positions.

Turns out that simple rule is enough to avoid all issues of arbitrary number representations. Yes we accept the tradeoff of not being able to represent very large numbers, but it will save us a lot of pain down the road. I know we’ve covered binary to a painful extent and it hasn’t gotten you any closer to understanding how a computer works, so I feel bad telling you that the next chapter is also about binary. But, once we cover this last piece of information, we will move on to the more interesting topics.

Let’s conclude this chapter by revisiting the original problem statement that motivated this issue. In a world where our rule applied, if the same stranger handed you a paper with only 0’s and 1’s on it and told you to decipher the values, you would now be able to. The first 8 bits should be treated as the binary representation of the first number, the second 8 bits correspond to the next number, and so on. In fact, if we know there are 100 numbers and our rule dictates each number is represented with a byte, then we would expect there to be exactly \(100*8=800\) bits on that piece of paper.

Chapter 05 - What about Negative Numbers?

Topics Covered: Two’s Complement, One’s Complement, Subtraction

By reading the title of this chapter, you probably realized I made a huge oversight in the third chapter: we never considered the possibility of a negative number. In this chapter, we will see how negative numbers are represented in binary and explore some related concepts.

In decimal, detecting and working with negative numbers is easy: you just prefix the number in question with the negation symbol, -. -845 is clearly a negative number, 845 is clearly a positive number, and 0 is neither. During the last chapter, I hinted at the idea that computers can only work with the presence or absence of electricity which we interpret as 0’s and 1’s. So, prefixing a binary number with a negative sign may work for just converting between binary and decimal on a piece of paper, but when it comes to building physical computers, this won’t get us very far.

So, how do we represent negative numbers if we can’t use the age-old negative symbol? As it turns out, there are a few different ways of solving this issue. Last chapter, we set a rule that all numbers in our computer will be represented with exactly 8 bits (i.e. a byte). This rule, as mentioned when introduced, will hold for the rest of this book. However, for the next few paragraphs we will consider nibbles which are 4-bit values (effectively a half-byte). This just makes illustration easier. But we will end the chapter with discussion of 8-bit values.

Recall that a nibble is a 4 bit value. We know the smallest value we can represent with a nibble is \(0000_2=0_{10}\). Similarly, the largest value we can represent is \(1111_2=15_{10}\). And if you recall from a previous chapter, we showed that with four bits, you can represent \(2^4=16\) different values.

The basic approach

In decimal, when we want to represent a negative number, we prepend the negative sign to the number in question. Although we don’t have a negative sign in binary, what if we just reserve the left-most bit for indicating if the number in question is positive or not. If the number starts with a 1, we interpret the remaining three bits as a negative number. Similarly, if the number starts with a 0, we interpret the remaining three bits as a positive number.

We know that the binary value \(101_2\) is equal to \(5_{10}\). In our proposed scheme this would mean that \(1101_2=-5_{10}\) while \(0101=5_{10}\).

For another example, we know that \(011_2\) is equal to \(3_{10}\). So under our schema, \(1011_2=-3_{10}\) while \(0011_2=3_{10}\).

This is pretty easy to understand, isn’t it! And hopefully you can see the value of the last chapter where we established a constant width for any number in question. By looking at any number, you can determine if it is positive or negative simply by looking at the value of the first bit. I pose the following questions: what is the biggest number we can represent under this schema and what is the smallest number we can represent under this schema? Since we are reserving the left-most bit for indicating the sign of our number, we are effectively reduced down to three digits for representing the number in question itself. With three digits, the biggest binary number we can make is \(111_2=7_{10}\). So, the largest number we can represent is \(0111_2=7_{10}\). As for the smallest number, don’t get confused and think it is 0 since we just introduced negative numbers! Instead, use the same idea that 7 is the largest magnitude we can represent, so \(1111_2=-7_{10}\) means that -7 is the smallest number we can represent. Under this scheme, we can represent -7 through 7.

Take a second and count how many different values that is: -7, -6, -5, -4, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Notice something? That is only 15 values but when we considered only positive values, we found we could get 16 values in four bytes. We know that with 4 bits we should be able to represent 16 numbers, so how did we possibly lose a value?

You may have already discovered the solution, but the issue involves attempting to represent zero. Although \(-0\) isn’t really a meaningful concept, our scheme allows us to both represent \(0_{10}\) as \(0000_{2}\) and \(-0_{10}\) as \(1000_2\). The issue is that we are wasting two different binary strings on representing the value zero, when we only need one.

I know what you are thinking: thats barely any information lost and isn’t a big deal. But, computer designers wouldn’t ever settle for that tradeoff. With computers storing the mass amount of information they do now combined with the incomprehensible amount of mass data collection that is constantly occurring, this wasted space would actually add up to be quite an expensive tradeoff.

Even then, that’s not the only issue. If we were to use this design, adding numbers would become quite difficult. Sure, we could probably design some algorithm that would work, but the easy-to-understand idea of stacking numbers on top of each other and adding corresponding digit positions from right-to-left wouldn’t work here. So, we abandon this idea.

Two’s Complement

It turns out there’s another way of handling negative numbers that doesn’t waste any space (i.e. we can represent 16 different values with 4 bytes instead of 15). Even better, the normal, intuitive way of adding numbers still holds. And, as we will see afterwards, subtraction is easily accomplished.

The Big Idea: Negate the value of the higest order bit and treat every other bit position the same.

This new, preferrable approach is called Two’s Complement. That’s all there is, I promise. But let’s take a few minutes to digest this claim and look at the consequences. Still, we are working with nibbles.

What does this big idea really tell us? Remember how each digit position corresponds to a different power of two. The right-most digit has a weight of \(2^0=1\) and then the next digit has a weight of \(2^1=2\) and so on. This is saying that the left-most digit, has a weight of \(-2^3=-8\). The numerical interpretation of every other digit position remains the exact same, but with the left-most digit, we assign it the negative weight.

Under Two’s Complement, lets try convert the value \(1001_2\) to decimal. Using the expansion rules we learned about in the third chapter, we know that this expands out to be \(1*-2^3 + 0*2^2 + 0*2^1 + 1*2^0\) which simplifies down to \(1*-2^3 + 1 * 2^0\) which further reduces to \(-8+1=-7\).

Let’s try another example by converting \(1111_2\). In long form this gives us

\[1*-2^3 + 1*2^2 + 1*2^1 + 1*2^0\] \[-2^3 + 2^2 + 2^1 + 2^0\] \[-8 + 4 + 2 + 1\] \[-1\]This still means we can represent positive numbers without issue. Try convert \(0111_2\)

\[0*-2^3 + 1*2^2 + 1*2^1 + 1*2^0\] \[1*2^2 + 1*2^1 + 1*2^0\] \[2^2 + 2^1 + 2^0\] \[4 + 2 + 1\] \[7\]In both of our approaches, we can tell if a number is negative by looking at the left-most bit. If it is 1, the number is negative and if 0 then positive.

Now, let’s answer the same questions we posed in the initial approach: what is the biggest and smallest number we can represent.

The Biggest Number: We know that the weight of the left-most digit is negative. So, whenever we set that bit position to 1, we are subtracting from our total value. For the remaining three digit positions, their weights are all positive and add to the total value. So we can get the largest value by setting the negative-weighted position to 0 while setting all the positively weighted positions to 1. This is \(0111_2=7_{10}\).

The Smallest Number: We know that the weight of the left-most digit position is negative which means that position helps bring our number down. The other three positions are weighted positively which help bring our number up. Therefore, to get the lowest value possible we want to set the bit position of the negatively weighted slot to 1 while leaving all others as 0. If we turned any of the other three bit positions to a one, we would be adding a positve increment to our value which would stray us away from the answer. So, this is \(1000_2\) which in decimal is \(-2^3=-8\).

So the smallest value we can represent is -8 and the largest is 7. You can represent any value in between (it would be a good exercise to stop and do that now). Unlike our previous approach which let us represent -7 through 7, we have found a way to represent the values -8 through 7 using the same amount of space! This is pretty cool. And it turns out we can’t do better than this because we have represented 16 values in 4 bit positions, which from earlier, we know to be the highest amount possible.

Oh - and in Two’s Complement, there is no such thing as -0 and 0. If you don’t believe me, try find two different binary values in this scheme that both evaluate to zero. The only one you will be able to find is \(0000_2\). Nice!

Converting Between Negative and Positive

You may be wondering, how do I take a negative number in base 10 and convert it to binary? It turns out, you can convert the positive reprsentation to binary, and then Two’s Complement has a unique property that makes negating numbers really easy.

How to Negate a Number in Two’s Complement? Invert every bit position (i.e. \(0\Rightarrow1\) and \(1\Rightarrow0\)) and then add one to the result. You don’t need to worry about why this works, but moreso on how to do it.

Let’s try an example. Suppose we want to represent \(-5_{10}\) in binary. Well, we know that 5 in binary can be represented as \(0101_2\). So our rule says we first invert every bit position. So let the 1’s become 0’s and vice versa. After this, we have \(1010_2\). And then the second step of the rule says to add 1 to the value. So we perform \(1010_2 + 0001_2\) and obtain \(1011_2\) as our final result. We can verify this by converting \(1011_2\) back to decimal and expect to get -5.

Here’s the work:

\[1*-2^3 + 0*2^2 + 1*2^1 + 1*2^0\] \[1*-2^3 + 1*2^1 + 1*2^0\] \[-2^3 + 2^1 + 2^0\] \[-8 + 2 + 1\] \[-5\]This should be impressive! This simple two step process allows us to negate numbers incredibly quickly.

Binary Subtraction as Addition

When I introduced binary, I showed how to add numbers but sneakily ommitted any discussion of subtraction. That was intentional, as I was waiting to introduce the concept of negative numbers before visiting this topic.

Suppose you are subtracting two numbers \(X\) and \(Y\). Then it should be pretty evidence that \(X-Y = X + (-Y)\). In English: “X minus Y is equal to X plus negative Y”. So, to subtract Y from X, all you need to do is negate Y and add that value to X. So, instead of us having to devise a new algorithm for subtracting numbers in binary, we can use two algorithms that we already know: one being negation of a binary number and the other being addition of two binary numbers.

And it turns out, for reasons we won’t concern ourselves with, addition in Two’s Complement works out the exact same as the previously discussed algorithm (try add some combinations of positive and negative numbers if you don’t believe me).

We will illustrate this topic with one problem: what is \(6_{10}-4_{10}\) in binary? We know the answer is \(2_{10}\) and can quickly convert that to binary and obtain \(0010_2\), but let’s work it out the long way for sake of illustration.

First, we convert 6 and 4 into binary to respectively obtain \(0110_2\) and \(0100_2\).

Then, we take our representation of 4 and negate it to get -4. We do that by inverting all the bits (\(1011_2\)) and adding 1 to get \(1100_2\).

We then add this to the representation of six to get \(0110_2+1100_2=0010_2\) And we know that is the correct binary representation of 2! If you paid attention closely, you noticed how the left-most bit got carried out from being a 1 to a 0 which is pretty cool since that is how our final result is positive (as it should be).

Back to 8-Bit Numbers

You’ve made it. I’ve explained the vast majority of all the binary concepts we need to know before we can start designing our computer. The last thing I will do in this chapter, is reinstate our understanding of 8 bit values. Two’s Complement works in 8-bit values as well. The left-most bit (\(2^7\)) has its value negated so its weight is \(-2^7\). The other bit positions remain the exact same.

So, the smallest number we can represent in a byte using Two’s Complement is \(1000\ 0000_2=-2^7_{10}=-128_{10}\).

The largest number we can represent is \(0111\ 1111_2\) which equals, if you work it out, is \(127_{10}\).

So, in a byte, we can represent any whole number in the range of \([-128, 127]\)

That covers all we need to know before we can start moving on to the interesting stuff in the next chapter!

Chapter 06 - Logic Gates

Topics Covered: Elementary Logic Gates, Truth Tables, Basic Circuits, The Universal Gate

Now that I’ve made you suffer through enough chapters of binary, it’s time to introduce a seperate yet similarly related concept: logic gates. There’s a few different types of logic gates we will need to understand, so I will introduce them one-by-one and then we will circle back and understand the bigger picture. This chapter should (hopefully) be a lighter read compared from the last few which probably involved you using a calculator to double check everything I was saying.

Simply put, a logic gate takes in a variable number of inputs (atleast 1) and produce a single output. The interesting part, that that all the inputs and outputs are either 0’s or 1’s. We have spent a few painful chapters understanding the nuances of binary, but you can put that aside for this chapter. In the next chapter, the connection between this chapter and all the previous ones will become apparent.

AND Gate

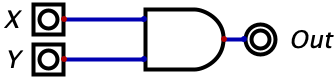

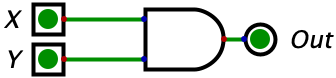

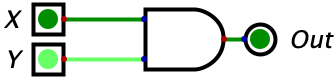

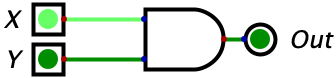

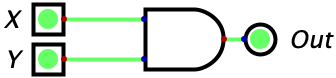

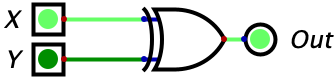

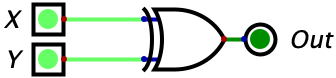

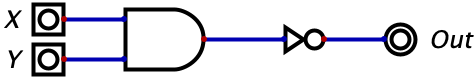

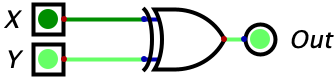

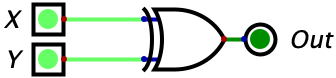

Let’s start with the AND gate which takes in two inputs, and produces one output. If both of the inputs are 1, then the output of the AND gate is 1. For any other combination of inputs, the output will be a zero. The following image is what an AND gate looks like: X and Y serve as the two inputs and the output is given on the right hand side.

Recall that, in the picture above, X and Y are binary inputs. So X can be either 0 or 1 just as Y can be either 0 or 1. We know that the only time that Output=1 is when \(X=1\) and \(Y=1\). Another way to view the functionality of the gate is by giving a truth table. A truth table is a table (duh) that enumerates all of the different possible input combinations on the rows while providing the output of the logic gate on the right-most column. See the table below. There are only four rows in this table, because with two binary inputs, there are only four different input combinations (try invent another one if you don’t believe me).

Remark: For the following diagrams (and all diagrams in subsequent chapters), the darker green is used to represent a 0 while the brighter green represents a 1. The lines on the diagrams are wires, and the only thing you need to recall is that when we put a 0 or a 1 on a wire (i.e. electricity or no electricity), the wire will conduct that value over it’s entire length.

AND Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | AND | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

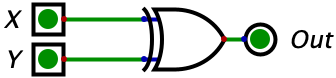

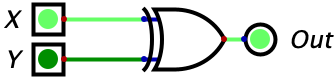

OR Gate

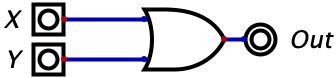

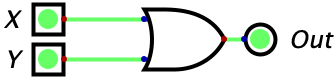

Now, lets move on to the OR gate which also takes in two inputs. The difference here is that this gate will output a 1 whenever atleast 1 of the inputs is 1. If both of the inputs are a one, the output of the gate will still be 1. It also does not matter which of the inputs is 1, the output will be 1 as long as either of the gates is 1. With this information, we can reason that the only time an OR gate will ever output a 0 is if both of the inputs are 0’s. Here’s what an OR gate with inputs named X and Y looks like:

Just as we gave a truth table for the AND gate, below is the truth table for an OR gate.

OR Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | OR | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

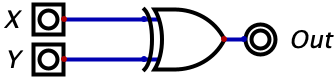

XOR Gate

Similar to the OR gate is the XOR gate which means “Exclusive OR”. The difference between this gate and the regular OR gate is that this will only output a 1 if exactly 1 of the inputs is 1. So, if both of the inputs are 1’s, then the gate will output a zero. Besides this, the other three rows in the truth table remain unaffected. A picture of the gate and truth table are given below.

XOR Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | XOR | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

NOT Gate

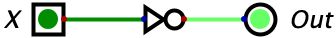

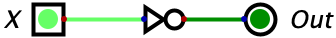

The NOT gate, sometimes called an inverter, is different than the rest we have considered so far because it only takes in one input. Since there is one input and the input is binary, we know that the truth table will only have two rows to represent the two sole possible input values. The inverter will output the inverse of the input. So, 1’s become 0’s and vice versa. Below is an image of an inverter followed by its corresponding truth table.

NOT Gate Truth Table:

| X | NOT | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 |  |

NAND Gate

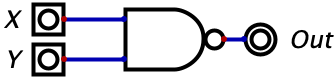

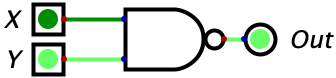

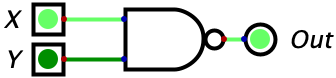

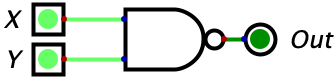

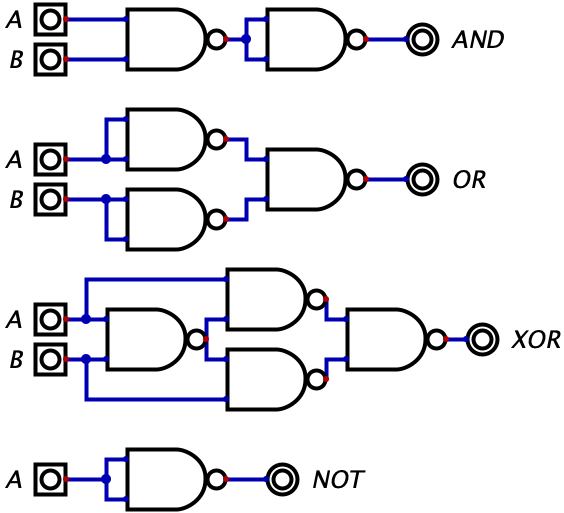

Now we move onto the the NAND gate which, in English, reads “Not AND”. This gate will take whatever the output is of the AND gate and invert it. The NAND gate will output a 1 unless both inputs are 1’s in which case it will output a zero. This means the the truth table will be the exact opposite of the AND gate’s truth table. The diagram and truth table are given below.

NAND Gate Truth Table:

| X | Y | NAND | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

What’s interesting is that the NAND gate can be constructed by taking a regular and gate and then feeding the input through a NOT gate. This is entirely valid, we can chain logic gates together to build more powerful circuits. So, this circuit below is functionally equivalent to a NAND gate.

We have subtly introduced a new concept: logic circuits. When we feed the output of a logic gate into the input of another logic gate, we can create more useful and complex circuits. Whereas a logic gate always takes in one or more input and produces a single output, a logic circuit takes one or more inputs and produces a variable number of outputs. We will see this in action in future chapters.

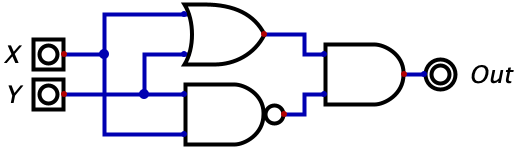

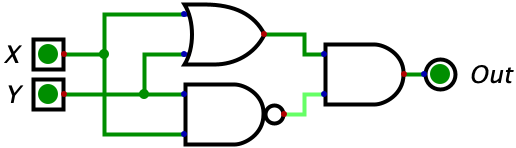

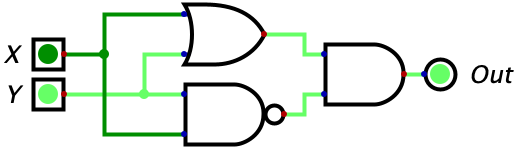

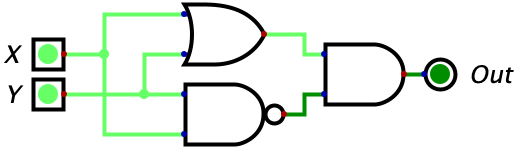

Similarly, we can construct the XOR gate with the following combination of other logic gates.

We can verify this is equivalent by comparing the truth tables.

| X | Y | XOR | Picture | New Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

|

| 0 | 1 | 1 |  |

|

| 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

|

| 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

|

This one is a little bit harder to understand. The easiest option is to create a truth table for this circuit and then compare it against the truth table for the XOR gate to see that they always output the same value for any input. If you’re like me, this alone won’t satisfy you since you want an intuitive explanation. Here is how I would reason through this: the circuit ends with an AND gate which means it only outputs a 1 when both of the inputs are 1’s. How do we make the first input a 1? The first input to the AND gate will be a one whenever X or Y is true since the input to the AND gate is the output of an OR gate. How do we make the second input to the AND gate a 1? We make the output of the NAND gate a 1. This happens as long as the inputs are not both 1. So we know the two conditions, and we need them to be true simultaneously. So putting this together, we can reason that the circuit will only output a 1 if “atleast X or Y is a 1 BUT not both of them are 1”. And this is exactly how we described the XOR gate!

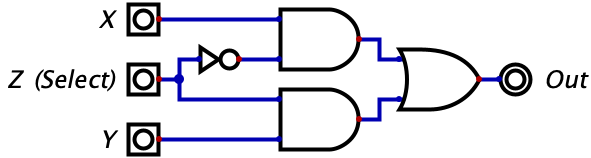

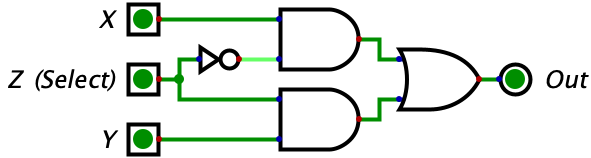

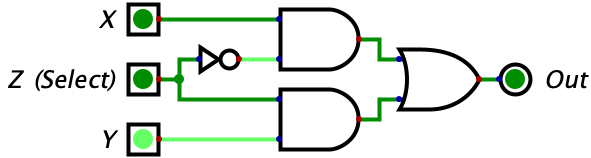

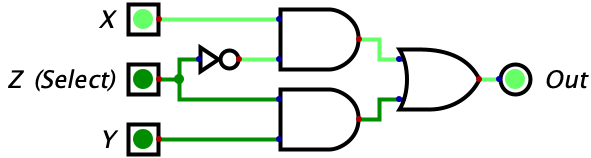

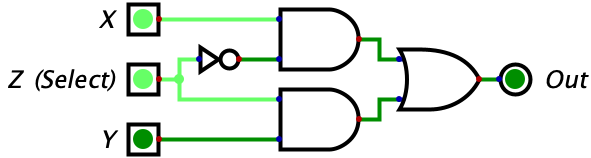

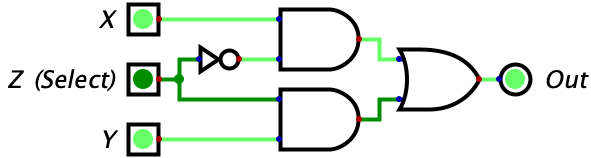

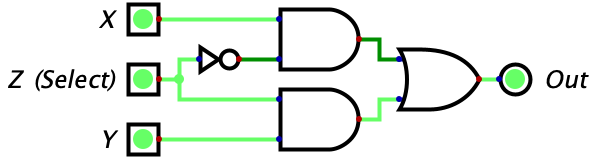

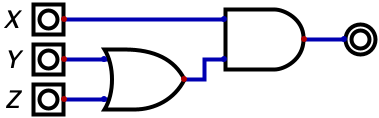

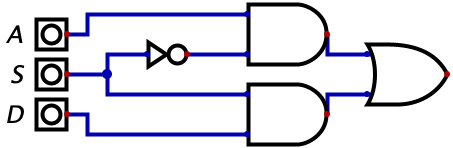

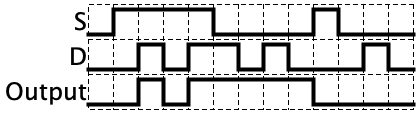

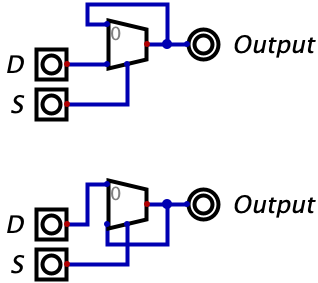

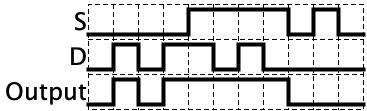

These few logic gates may seem very simple to understand compared to binary, but it turns out they can be chained together to do some pretty interesting things. Consider the circuit below with three inputs which, at first glance, probably looks like gibberish. But if you make a truth table for it, you will see that the circuit is a switch. Whenever Z is 0 the gate outputs whatever the value of X is. Whenever Z is 0, the gate outputs whatever the value of Y is. So, Z is effectively switching the output between X and Y. Pretty neat!

The truth table has been given below, but you should try complete it on your own.

| X | Y | Z | Output | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

Let’s try make some sense of this logic diagram intuitively. We notice that the output of the entire circuit is the two values of the AND gates OR’d together. So, as long as one of the AND gates is outputting a 1, then the entire circuit will output a 1. However, if neither of the gates output a 1, then the entire circuit will output a zero. Then, we look at the two AND gates and make the powerful observation that the input Z is being fed into both of the AND gates (although one is indirect). The value of Z feeds straight into the bottom AND gate while the top AND gate recieves the negated value of Z. This means that whenever Z is equal to 1, a 0 is fed into the top AND gate while a 1 is fed into the bottom AND gate. Conversely, whenever Z is equal to 0, a 1 is fed into the top AND gate while a 0 is fed into the bottom AND gate.

Why does this matter? Well we know that an AND gate will only output a 1 if both of its inputs are 1. Combine this with the fact that, for any value of Z, one of the AND gates will recieve a 1 for one of its inputs while the other will recieve a 0. The AND gate that recieves a zero will automatically output a zero, regardless of it’s other input, since this is a property of the AND gate (i.e. needing both of its inputs to be 1s for output to be 1). So, the value of Z will effectively shut off one and gate by giving it a 0 for an input.

When Z is 0, the bottom AND gate is ‘shut off’ and outputs a zero. So, the output of the overall circuit is equal to 0 OR’d with the output of the top AND gate. Since the OR gate only turns on when one of the inputs is a 1, and we know one of the inputs is already a 0, we can reason that the output of the entire circuit will equal the output of the upper AND gate. So, what is the output of the upper AND gate? It would be 1 (from Z) OR’d with the value of X. With similar reasoning, we can see that this simply equals the value of X. So, when Z is 0, we allow the value of X to ‘flow’ through the circuit to the output. We also can see how there is no possibility of interference since the entire bottom half of the diagram is guaranteed to be zeroed out in this case.

When Z is 1, the exact reverse thing happens! The top AND gate is forced to output a zero since one of its inputs is a zero. Then, the output of the entire circuit equals the output of the bottom AND gate. The output of the bottom AND gate equals the value of Y since we know the other input is the 1 coming from Z. So, the output of the entire circuit is the value of Z.

For some readers, everything I just said will make sense. For others, however, only half of what I just explained will click. Don’t read ahead until you are able to clearly understand what was just written. This is a new concept, so don’t be discouraged if it doesn’t immediately make sense. On top of it being a new concept, I am also intentionally introducing this to you at a fast pace to avoid getting into the nitty-gritty.

A better way of expressing circuits

So far, I have been using diagrams to visualize circuits, but only using diagrams will become complicated as we move forward in the next chapters. Instead, it would be nice if we could represent some of these diagrams using just text. Fortunately, this problem has already been solved, so we will spend some time here seeing how we can express logic gates in a textual form. For this subsection, lets assume that \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), or any letter is a binary input (i.e. a variable that takes on either the value 1 or the value 0).

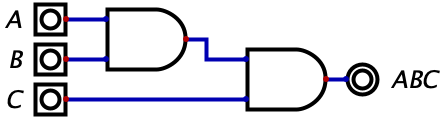

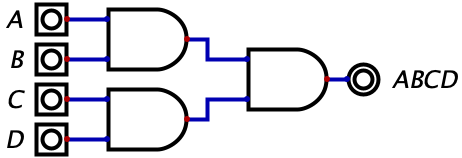

We start with the logical AND expression, which can be represented with multiplication or the absence of a sign. So, \(A*B\) and \(AB\) are equivalent expressions that read in English as “A and B”. With just two inputs, this can easily be translated to a simple logic gate with two inputs. If we gave the expression \(ABC\) (equivalent to \(A*B*C\)), then this translates to “A and B and C”. But the AND gate we learned about only takes two inputs? Well, logical expressions and logic circuits are very similar, but you usually need to find a way to express a logical expression using logic gates. In the case of \(ABC\), we can easily invent the circuit below:

We could even scale this up to any number of variables. Here’s how the expression \(ABCD\) would look like as a circuit:

Before we move on to see how we can textually represent other logic gates, let’s understand why we use multiplication for representing the logical AND. Recall that in an expression, all of the variables (\(X\), \(Y\), \(Z\), etc.) are binary inputs. When we go to evaluate a logical expression, we substitute in 0’s and 1’s accordingly for all of the variables and after some manipulation, expect to end up with either 0 or 1 (because the expression has to evaluate to a single binary value). So, if you recall from your high school algebra class, if we multiply anything by zero, the final output is zero. So when we have an expression such as \(X*Y*Z\), if any variable is zero, then the entire thing resolves to zero, and the only case which this can evaluate to a 1 is if all three variables are one. It’s convenient that our notation for logical expression abides by basic algebraic properties since it eases your intuitive ability to grasp what an expression is saying. The reason we can omit the explicit multiplication signs (\(XYZ\) instead of \(X*Y*Z\)) also relates to algebra. If \(P\) is a variable, then algebra tells us that \(5p\) is equivalent to \(5*p\), so in the latter case, the use of the multiplication sign isn’t required since we can infer that a lack of an operator means to multiply the two operands.

So, we’ve seen how the logical AND can be represented in this written form, so how do logical OR’s work? The answer is with addition. \(X + Y\) reads out to “X or Y”. Similarly, \(X + Y + Z\) reads out to “X or Y or Z”. The (roughly speaking) reason we use the addition sign to represent logical OR is because you need only one of the variables to evaluate to 1 for the expression to be true (i.e. \(0 + 1 = 1\)).

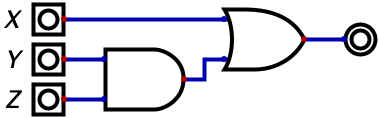

Just as logic gates can be chained together, operators in a logical statement can be chained together. For example \(X + YZ\) would translate to “X or both Y and Z”. With logic gates, this would look like the diagram below.

As is the case with algebra, the use of parenthesis is valid (and often necessary). That PEMDAS acronym you haven’t heard in years is valid here for specifying order of operations in that parenthesis should be evaluated before multiplication which should be evaluated before addition (the rest of the operators in PEMDAS don’t really exist in our means of representing expressions). For sake of illustration, the following expression is visualized by the diagram below: \(X(Y + Z)\)

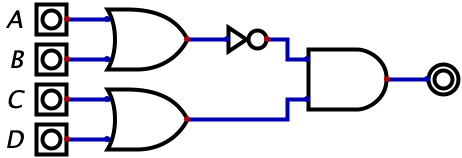

For logical negation (NOT), there are two different but equally valid representations: \(\neg{X}\) or \(\overline{X}\). You will see these used interchangeably online, but for the sake of this book, we will stick to the latter representation. So the expression \(\overline{(A + B)}(C + D)\) can be represented with logic gates accordingly:

To represent XOR, we have this odd looking symbol: \(\oplus\). So \(X\oplus Y\) is the exclusive-OR between variables X and Y.

As it turns out, those three operators combined with the order of operations you already know intuitively are enough to represent any combination of logic gates. For example, although we don’t have a NAND symbol, we can represent NAND with an inverted AND: \(\overline{XY}\)

As you can probably imagine, these expressions can get incredibly complicated and virtually impossible to read. There is an entire field of study that involves simplying expressions down as much as possible. In many cases, it is easy to take a convoluted expression and simplify it down to a more readable expression. For example, the following expressions are logically equal but the second is more readable than the first: \(AB + DA + AC \equiv A(B + D +C)\) (The triple equals is used to show logical equality). Reducing expressions can get complicated rather quickly, and I don’t want it to be a primary concern of this book. As we introduce and simplify expressions in the future, you will either be presented with the steps taken to simplify the expression or given the final reduced expression. In either scenario, you do not need to focus heavily on how the statements were simplified, and it is safe for you to accept our simplified equations as the truth.

That being said, there are two famous simplifications that I will provide below. These simplifications are called De Morgan’s laws and come up frequently in expression simplification. You should take some time to reason through why the two claims are logically true.

\[\overline{AB} \equiv \overline{A} + \overline{B}\] \[\overline{A + B} \equiv \overline{A}\ *\ \overline{B}\]The Bigger Picture

We have now introduced these very basic structures called logic gates. You immediately saw how they can get complicated when you start chaining them together, but that such combinations actually enable you to build rather interesting circuits. I will now make a claim which, barring one or two minor exceptions which we will later address, is both true and remarkably powerful.

Claim: computer processors are built entirely of logic gates. You might be reading that in denial, but this is the unexaggerated truth: logic gates are the building blocks of computers. By chaining hundreds, millions, or even billions of logic gates together, you can build a fully functional computer. And that is the exact goal of this book.

You saw how we can chain logic gates together to build a switch, so in the coming chapters we will explore more complex yet powerful arrangements of logic gates that implement other useful circuits. We will then combine these known circuits together to build an entire computer.

If logic gates can be used to build computers, and you are holding a physical computer in your hand right now, does that mean logic gates physically exist? The answer is yes, you can seriously purchase a 10 pack of AND gates on Amazon for $6.

Let’s actually take a minor digression to see how the physical chips work. If you click the link, you’ll quickly see that the AND gate on Amazon looks nothing like the AND gates in our logic diagram.

In the diagram, pins 7 and 14 are used to power the chip, so we can ignore those. Look at the first three pins, however, and you will see an AND gate. The first two pins are the input while the third pin is the output. This means that if you connect pins 1 and 2 to wires and then place electricity on the both of the wires (hence the AND), the chip will put electricity onto the third pin. Looking at the rest of the diagram, you can see that there are a total of four AND gates on this chip. You do not need to understand how these chips are physically built, and if I’m being honest, I don’t have the clearest understanding myself. We will build our computer strictly using logic gates, and that will be the lowest level of understanding we have for how this computer can be physically built. If you really, really want to know how logic gates are physically built, there is an abundance of resources online, none of which make perfect sense to me. So yes, perhaps I lied a little bit in the introduction when I claimed that you would understand how a computer works from scratch. In reality, you will understand how computers work down to logic gates, and we will leave that very lowest level of physically building the gates aside. For those of you curious, there is actually a really neat article about someone who implemented logic gates with water. If you’re looking for a little more explanation on how logic gates work but don’t want to go into the nitty-gritty of electricity, then this article should hopefully satisfy your craving.

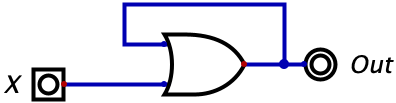

The Universal Gate (Optional)

This chapter has already covered enough material, and I don’t want to distract you by adding even more to that load. But, there is one concept that I remember blowing my mind when I was first learning about logic gates.

The mindblowing fact: All logic gates can be constructed by using NAND gates. If you don’t believe me, then take a look at the diagram below which shows some of the gate construction and verify that the truth tables work out equivalently.

We previously claimed that you can build an entire computer out of logic gates. Now that we know the NAND gate can be used to construct any other logic gate, we can make the secondary claim that you can build an entire computer solely using NAND gates. This is pretty neat!

Chapter 07 - Addition with Logic Gates

Topics Covered: Half Adder, Full Adder

Now that we have learned about logic gates, I think it’s time we learned why they are so important (hopefully, the not so boring part). The average computer today can process around billions of operations per second which is mind-blowing. However, those processes can’t happen without the use of logic gates. Logic gates allow us to build more complex circuits inside of computers which allow these kinds of processes to occur. Let me back up for a second here. I think the best way to describe logic gates is comparing them to legos. In Chapter 6, we got introduced to the brick blocks, the tile blocks, the plate blocks, etc. Now, it’s time for us to take those different lego pieces and build our first house.

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, we can use these logic gates to build more complicated circuits. You might be thinking what does he mean by more complicated circuits (I promise we will start out easy). The simplest circuit that we can have is an adder. Let’s take an example below:

Above we have a circuit representing the equation \(A+B=X\) (in other words, \(0_{2}+0_{2}=0_{2}\)). In this example, what we are trying to demonstrate is that the OR gate can be used to add two numbers together.

Aside: In the example above, the A, B, C which are all 0s are not the number 0, but the bit 0, which is equivalent to the number 0. So, technically, we are adding the bit 0 (the number 0) to another bit 0 (the number 0) giving us the bit 0 (the number 0). Review Chapter 3 if this does not make sense!

Let’s look at a slightly different example:

Here, we are adding the bit 0 (number 0) with the bit 1 (number 1) which gives us the bit 1 (number 1). Makes sense right? I know I’m definetly boring you, so let’s look a slightly harder example:

Here, we are adding the bit 1 (number 1) with the bit 1 (number 1) which gives us the bit 1 (number 1). If you realized there’s a mistake here, you’re right. The number 1 plus the number 1 should be returning the number 2 (written as 10 in binary - notice how we need two bits). You might be thinking that there is no possible way we can represent the number two with just one OR gate (since it only outputs one bit). This is where things get exciting.

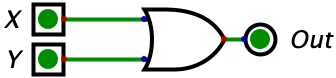

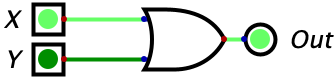

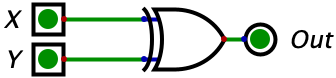

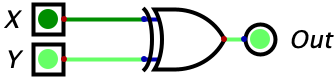

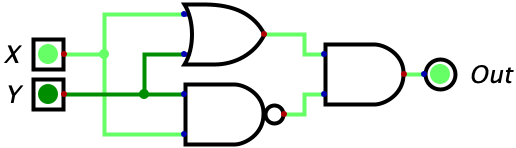

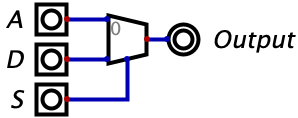

Remember when I was talking about legos earlier, this is where we use them. Just like how we can connect different legos with each other to build more complicated things, we can connect different logic gates to build more complicated circuits. Here is where we introduce the half adder:

The issue with using just an OR gate to represent the addition of two bits is that sometimes the bits can add up to the number 2 which we saw in the example in the paragraph above (meaning we need to somehow represent two bits in the output of a circuit since the number 2 is represented by two binary digits). This is where a half adder is useful because we can now represent the sum and carry out digits (which was talked about in Chapter 3). In the circuit above, the X acts as the least significant bit (the sum bit) and the Y acts as the most significant bit (the carry out bit). Now, your question might be how did we know to use the XOR gate to calculate X and the AND gate to calculate Y? Take a look at this truth table below:

| A | B | X (Sum) | Y (Carry Out) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Before we go any further, we should note that these calculations are the same as the ones in Chapter 3. First, looking at the Sum Column (X Output), we can see that it looks pretty familar to one of the truth tables in Chapter 6. If you were thinking an XOR gate, then you’re right! And, looking at the Carry Out Column (Y Output), we can see that the output looks similar to an AND gate. Now we can see why the half adder uses a XOR gate and an AND gate instead of using a normal OR gate.

If we combine both of these bits together (in the form of YX with the X bit being the least significant bit and the Y bit being the most significant bit), we can have an output now that represents the equation \(1_{2}+1_{2}=2_{10}\) because the number 2 can be represented as 10 in binary. Here is an example of the circuit below:

Here is another example of using a half adder for the equation \(1_{2}+0_{2}=1_{10}\):

In this example, we can see that the output is 01 (or the number 1). Again, the X is used as the least significant bit and the Y is used as the most significant bit.

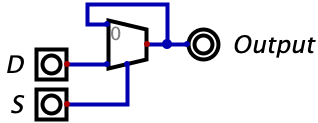

Remember how we were talking about lego bricks earlier? Well, you might hate me, but we are going to add another brick on top of our current circuit. Let’s say we want to add another input to our circuit and call it the carry in bit (this will make a lot more sense, I promise). So now we want to add the A, B, and C bits together to output a sum bit (X) and a carry out bit (Y). Let’s take a look at the truth table and build the full adder circuit:

| A | B | C | X (Sum) | Y (Carry Out) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

We can use the explanation from Chapter 6 to construct and simplify an expression for the truth table above. Let’s create an equation for the Sum bit:

- Start with the initial expression from the SOP rule learned in Chapter 6:

- Use the distributive law to further isolate the equation:

- First, use the the rule \(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\) (here’s a challenge - try to create two truth tables for each of the expressions to check if they are equivalent) to simplify the first part of the expression:

- Then, use the rule \(\overline{X \oplus Y} = \bar X \bar Y + XY\) (you can use the truth table trick again to see if both expressions are the same) to simplify the second part of the expression:

- Wait a second! The expression now kind of looks similar to a rule we already used in Step 3 (\(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\)), so now we can simplify the expression to its final form:

Now, let’s look at how to find the equation for the carry over bit:

- Start with the initial expression from the SOP rule learned in Chapter 6:

- Use the distributive law to further isolate the equation:

- Use the rule \(X \oplus Y = \bar X Y + X \bar Y\) to simplify the first part of the expression:

- Use the rule \(X + \bar X = 1\) to simplify the second part of the expression:

- Use the rule \(X*1\) to further simplify the expression to its final form:

Now we have both of our equations. The equation for the Sum bit is \(A \oplus B \oplus C\) and the equation for the carry over bit is \(C(A \oplus B) + AB\). We can now build our circuit which is below:

Let’s trace through the inputs in our truth table and look at it’s respective circuit:

| A | B | C | X (Sum) | Y (Carry Out) | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |  |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |  |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |  |

Cool right? Now, you might be thinking how can we further build on this concept. In Chapter 8, we are going to introduce the idea of ripple Ripple Carry Adders which will allow us to combine multiple Full Adders together to do multi-bit addition and subtraction (and, you’ll see why the carry out bit was important to learn about)!

Chapter 08 - Ripple Carry Adders

Topics Covered: Ripple-Carry Adders, Adder-Subtractor

Now that we know how to do simple addition using half adders and full adders (which are used to do one-bit addition), I believe we are ready to learn more about ripple-carry adders (for, you guessed it, multi-bit addition). Remember, how I kept telling you that we’d talk about the carry-in bit. Well, get excited because this is the chapter where we get to learn why that bit was so important that we needed to create a half adder on steriods (the full adder).

Imagine now we are adding two numbers: 3 and 1. In binary format, we can represent 3 as 11 and 1 as 01. Essentially, our expression here can be represented as 11+01. Let’s add these values using a table.

| Third Bit (Carry Over) | Second Bit | First Bit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carry Over from Previous Column | 1 | ||

| Number 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Number 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Result | 1 | 0 | 0 |